Aiminanu

YYZ Artists Outlet, Toronto

May 13-July 8, 2017

By Carmen Victor

Innu-aimun is a language spoken by Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi) peoples across boreal and sub-Arctic areas of Labrador and eastern Quebec. Quebec City artist and photographer Anne-Marie Proulx selected the Innu-aimun word Aiminanu, which translates to “there is a conversation going on” as the title of a recent exhibition at YYZ Artists’ Outlet in Toronto. In Aiminanu, form follows function: ornamentation is limited and the elements that constitute the exhibition are freed of artistic conceit, with the exception of the conceptual choices driving the narrative.

Proulx chose words from a French–Innu-aimun dictionary and represents their translations textually and photographically. The walls on either side of the gallery space are painted black and white, and a large, ceiling-to-floor photographic mural of waves is displayed at the far end. A small marker is situated centrally within the expansive waterscape mural, marking a nebulous aquatic intersection where lake water transitions into ocean water, signifying a meeting place that marks conditions of inextricable convergence.

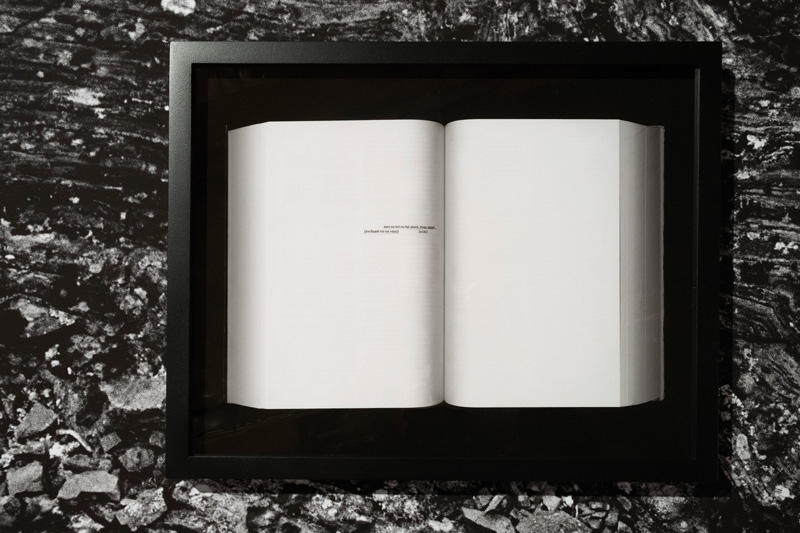

Mediating the walls’ stark, contrasting monochrome is a table covered with a photographic mural of striations of granite. The table points north, toward the meeting place of fresh water and ocean. Because it is oriented directionally north and the geography of the gallery architecture doesn’t necessarily align with compass points, the table appears slightly off kilter within the cube of the gallery space. Fourteen framed photographs of books open to primarily blank pages containing one or two minimalist lines of written text are placed around the gallery, three of them resting horizontally on the central table; viewers are forced to reorient their gazes and bodies in order to read the text. Essentially, the photographs are simulacra of books, and books are usually representations of knowledge, of dialogue, of passing on information that possesses the ability to speak across time. But these books, with pages that are primarily blank and inaccessible, represent a mystery. They represent words left unwritten, they signify what remains unsaid, a breakdown in communication, even though there is a conversation going on.

Accompanying the exhibition is a hand-out poster – a map of sorts. Sparse lines of text in French appear in the wall-mounted photographs of open books; they correspond to sentences in the diagram, which is written in Innu-aimun and French or English. For example, a photograph mounted on the black-painted portion of the wall facing north reads, in French and phonetic Innu-aimun,

Il disparaît au loin, à l’horizon

[n essinaːku∫u] [l ess enaːku∫]

The corresponding line on the handout provides a translation in Innu-aimun and English:

nissinakushu

she, he, it disappears in the

distance, on the horizon

The exhibition comprises sixteen phrases of similarly poetic translations in fourteen photographs of mostly blank, open books. Their sparse words can be decoded by examining the handout. This gesture encourages viewers to think across the language that they are reading – be it Innu-aimun, French, or English – or back and forth among the three. When translated into either French or English, single words in Innuaimun have layered, lyrical meanings. What could be said in one word in English or French becomes an entire sentence in Innu-aimun; and the other way around. The form undertaken here provides a horizon that fosters three-way convergences among language, text, and meaning, while situating notions of space and location with conceptions of territory, oral tradition, and memory.

Considering landscape, Lyotard claims that it is “the opposite of a place. If place is cognate with destination . . . landscape is a place without destiny.”[1] Proulx’s installation suggests a radical heterogeneity that encompasses indefinable boundaries as the product of an imaginary space-time while simultaneously depicting an actual, physical, yet difficult-to-reach place where the lake meets the ocean on Innu land in northern Quebec. The exhibition represents a transitory yet ceaseless topography in which relationality overflows comprehension, a nebulous, watery encounter that is somehow distinguished from knowledge.

Carmen Victor is a PhD candidate in communication and culture at York and Ryerson Universities. Victor’s writing appears in Seismopolite: Journal of Art & Politics, Culture Machine, Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review, and Prefix Photo magazine. She has an article forthcoming in the University of Liverpool’s Science Fiction Film & Television Journal and chapters forthcoming in Sculpted Cinema (Pleasure Dome, 2017) and Kelly Richardson: Pillars of Dawn (Art Gallery of Northumberland, UK, 2018). She is based in Toronto.

[Complete issue available here: Ciel variable 108 – GOING PUBLIC ]

Purchase this article