[Winter 1993]

by Suzie Larivée

“Portraiture consists of letting the richness of the interaction that passed between the subject and the artist — and between the subject and himself be made out, and of conveying the feeling of an intelligence in these subtle interplays.” ⎯ La Part de l’ombre1 by Régis Durand

“Now, people are telling me that I am a portraitist.” ⎯ Jean-François Bérubé, October 19, 1993

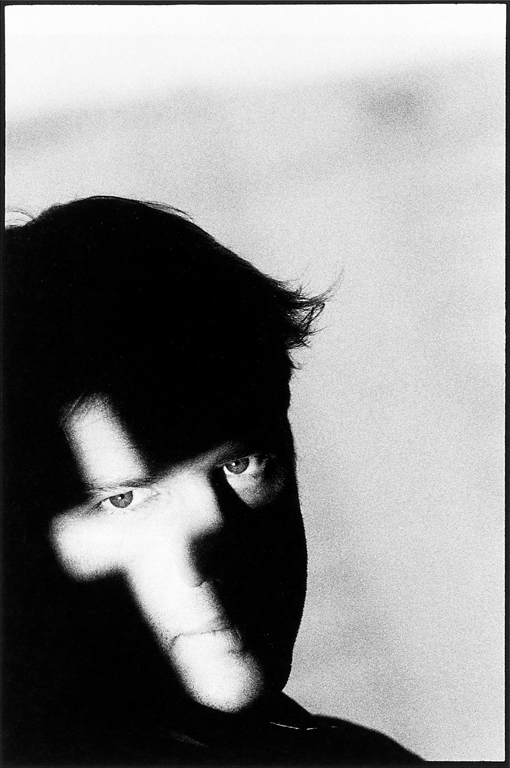

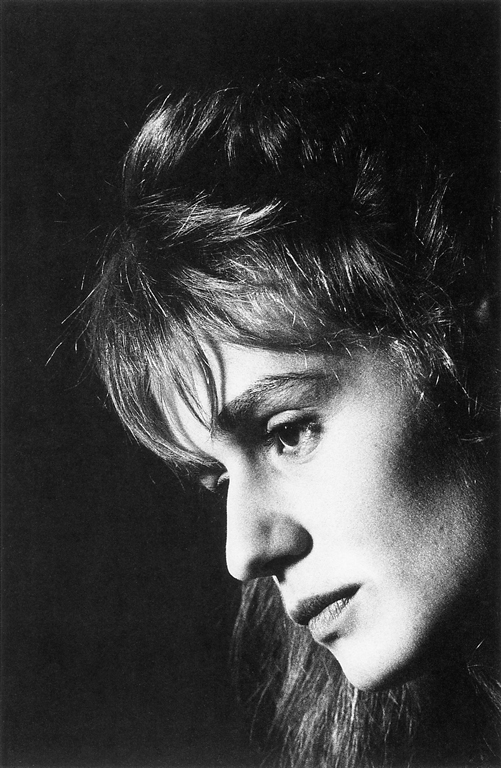

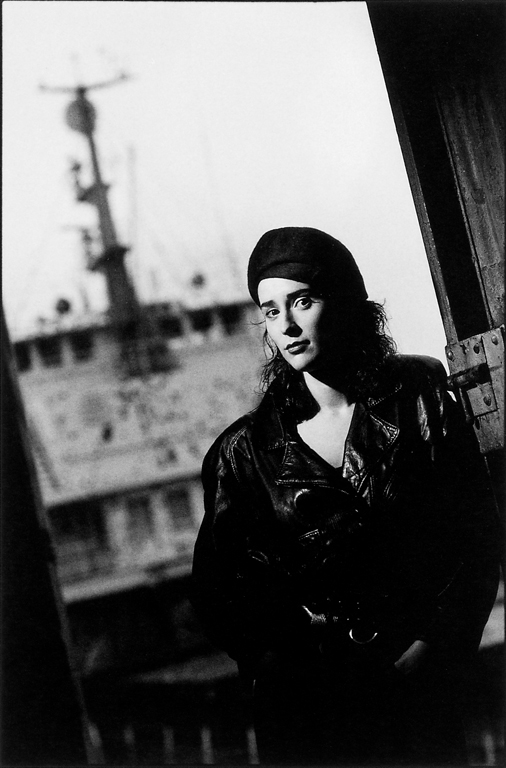

Profession: photographer and grand champion of the jeu du portrait. Several of his photos seen on the cover of the weekly VOIR as the weeks went by have been seen by thousands of people; others adorn record jackets and posters. Bérubé’s photographs are a part of the “cultural day-to-day” of a large audience.

In September, for the Mois de la Photo à Montréal event, our photographer was invited to show a selection of his works of the last several years (most of which had been taken for VOIR) in the St. Catherine Street West waiting hall of Montreal’s Place des Arts performing arts complex. See no disrespect therein for the quality of the artist’s works! Bérubé’s Portraits choisis (Chosen Portraits) the title given to the exhibition benefited once again from mass exposure, as they did when they were first published. Removed from the context of the weekly publication and brought together as a series, the photographs offered something gratifying to passers-by who found themselves, for a moment, fascinated by and jealous of the irresistible, intimate connection that seemed to have been achieved by the photographer and his subjects. Portraiture consists of “conveying the feeling of an intelligence in these subtle interplays”…

To portray – to delineate a body,to delineate a soul

In La chambre claire2Roland Barthes points out that the great portraitists are also great mythologists. In France, at the end of the nineteenth century, Nadar photographed the famous people of his time the actors, the writers and the philosophers. During the last several decades Avedon made hundreds of portraits of people from New York society life images that serve as witnesses of a society and which help to give it a face that perhaps will personify that society for a time to come. In the same vein, Régis Durand speaks of photographic portraiture as a decisive act that “generally condenses a set of symbols that establish a consistency and a belonging (psychological and social).”3Portraits as points of reference, in spite of the changeability of conventions.

Jean-François Bérubé also establishes a veritable gallery of portraits — portraits that capture Quebec’s cultural topicality: actors, musicians, personalities from the arts and theatre — all of these people belonging to the public domain, and rarely unknown by those who catch sight of them.

Occupying the centre-stage of our little “internal theatre,” most of Bérubé’s subjects occupy a role and are possessed of an image that is a product of both reality and fantasy coming close to what Durand calls the fable of identity. We all play the jeu du portrait: We assemble our perceptions of people with yeses and noes.

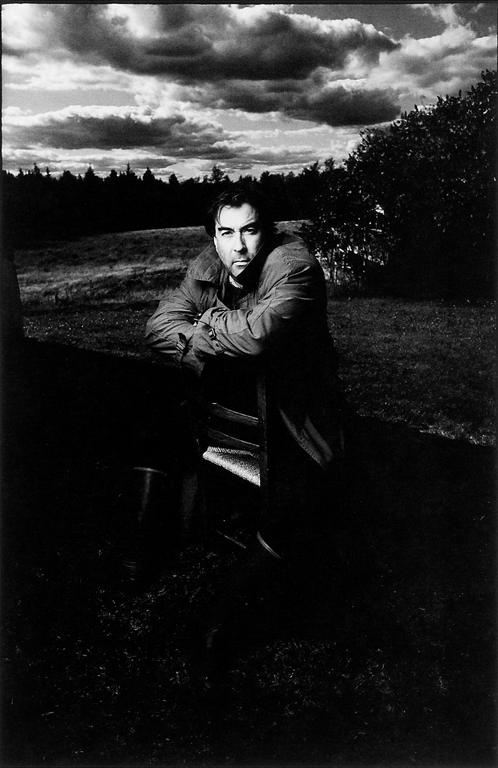

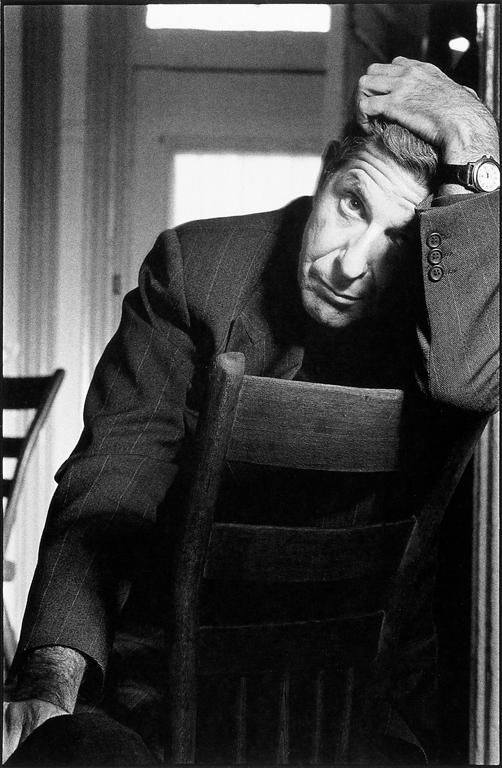

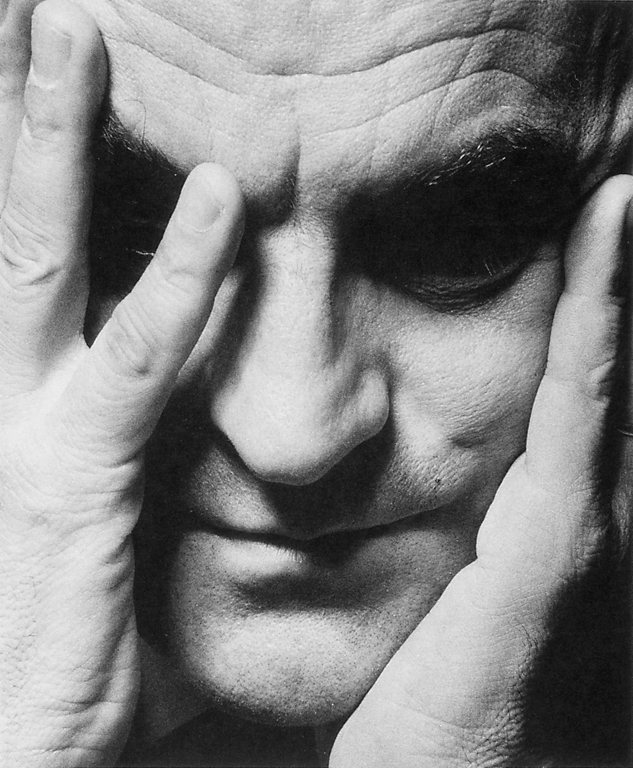

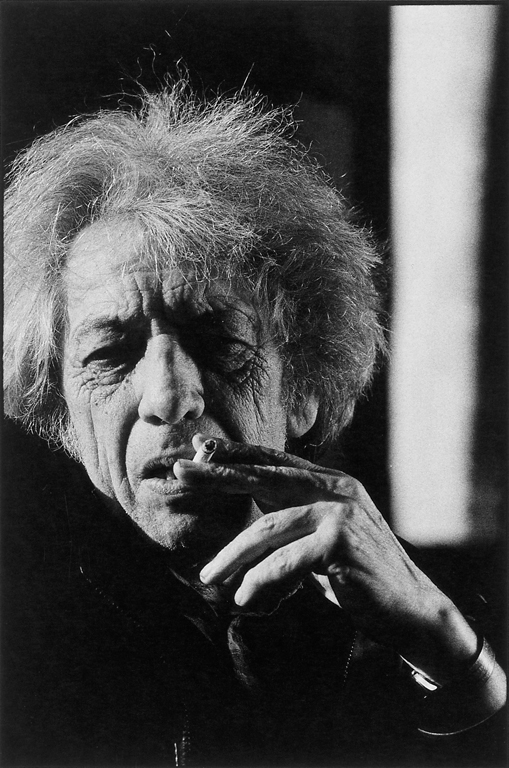

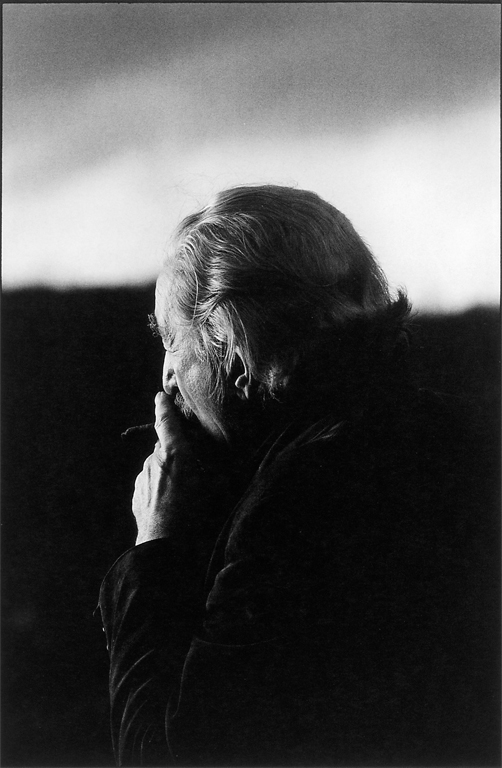

To make his photographs, Bérubé works in the studio or explores the environment of his subject. He sets a stage. The exercise gives rise to sober images, in keeping with certain traditions of the portrait: solitude of the subject, importance of the face, pronounced evidence of the hands, postures. The portraits of Michel Chartrand and Jean-Paul Riopelle which greatly move me present us with images of fighters, wild white hair, cigarettes jutting from the mouths. Density of the blacks, brilliance of the whites that permit the effects of the years to be seen: Faces — and hands as intense as the faces — become territories delineated by a network of lines, traits, wrinkles, and veins. And creases surrounding the eyes.

The strength of these portraits of men perhaps derives from the fact that they can be perused like the chapters of a life or, in a more abstract sense, as a rambling landscape of shadow and light — regardless of whether we recognize the “personage” portrayed.

Draw me a body, I will draw you my soul… The portraitist essentially offers us his vision of the world and of people, united with the play of identity introduced by his subject. The portraitist photographs what he sees, but he models his vision in the framing, the light, the use of accessories, and through an appreciable feat of staging. The photograph is an illusion, but the photograph “is still a testimony of truth”4in that it bears witness to a meeting, to a presence. “Portraiture consists of letting the richness of the interaction that passed between the subject and the artist — and between the subject and himself… ”

We will play the jeu du portrait. We will dispense with the questions. Draw me a body, I will draw you my soul…

2 Roland BARTHES. La Chambre claire. Note sur la photographie, Paris, Cahiers du cinéma, Gallimard/Seuil, 1980.

3 Régis DURAND, op cit., p. 54

4 Régis DURAND, Le Regard pensif – Lieux et objets de la photographie, Paris, La Différence, 1990, p. 67.

* Translator’s note: In the original text, the author makes a play on words with the French “portrait,” and calls repeatedly upon this word play in the development of her theme. Central to this wordplay is the French term “jeu du portrait” (which she defines for us at the outset), whose meaning is encompassed by the English “guessing game”; however, in the text, “jeu du portrait ” have been left untranslated, so that we may more readily follow the author as she associates this term with the more usual notion of a pictorial portrait. To assist her in her initial definition, the original French citation that she draws from Le Petit Robert has been partially translated for the reader.

A native of the Vallée de la Mata-pédia, Jean-François Bérubé was introduced to photography at a very early age by his late sister Suzanne. His formal education in photography was acquired at the Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel de Matane, and he has since refined his base of skills through his engagements as an assistant to well-known photographers. His photographs can be seen in numerous Canadian and Quebec publications. Bérubé regularly shows his work in solo and group exhibitions. His photographs reside in the Collection Prêt d’ceuvres d’art of the Musée du Québec and in private collections.

A native of Montreal, Suzie Larivée is finishing a Master’s degree in arts studies at the Université du Québec à Montréal. For the last several years, she has been chronicling the work of the artist Nicole Jolicoeur in an extensive collection of remarkable essays. In Issue Number 23 of CV photo, we were treated to a glimpse through her insightful eye in her commentary on the young photographer Nicholas Amberg. She has also written texts for exhibitions and has published articles in contemporary art magazines and catalogues. Suzie Larivée currently works for Montreal’s Maisons de la culture network.