[Hiver 1996-1997]

There is the moon, the darkness, the ghost of industry. André Jasinski photographs urban remains at night. He highlights their grandeur and lonely poetry. And he sniffs out the scourges that shaped them.

by Jennifer Couëlle

Although the city and its structure were signs of modern dynamism and faith in machines, celebrated for the geometry of their shapes, in the landscape photography of the early twentieth century, the gears of modernity and the autonomization of the object simply no longer pertain today. (We won’t discuss the exceptions here.) Following in the footsteps of the at first few and now growing numbers of photographers who have sought out the distinctive signs and traumas of industrial and post-industrial landscapes since the end of the fifties, Brussels photographer Jasinski finds wasted sites and decrepit buildings, waits for darkness, and aims his viewfinder.

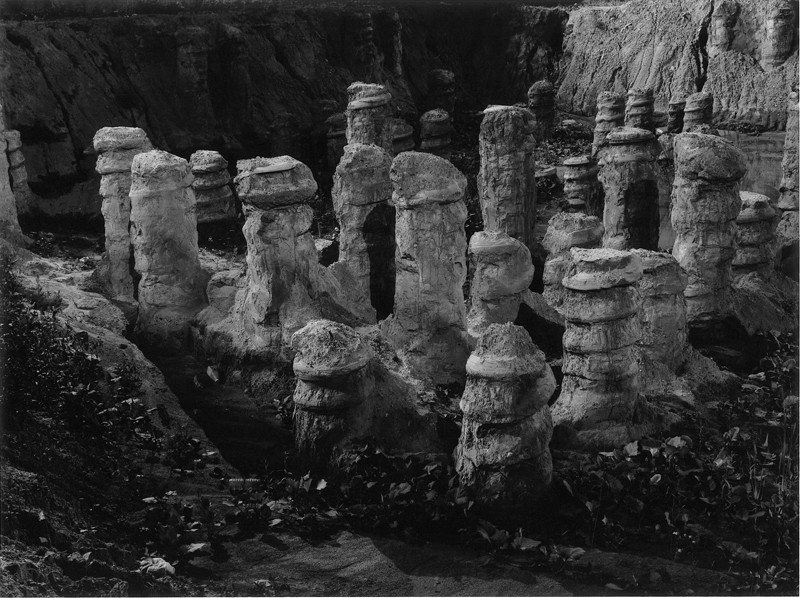

Most of the photographs presented here, taken during a group assignment to rediscover images of Geneva and Brussels and shown last year in the exhibition La Ville et son cliché — regards croisés Bruxelles-Genève, plunge us into a damaged or worn-down urban environment, denuded of all human presence – except for that of the photographer, with whom we share the manifest slowness of his gaze. With the moon as their sole source of light, these night-condensed images require, one might imagine, a prolonged exposure time, during which the glow from the nocturnal sky enters the black box and imprints upon the film a symphony of greys, unexpected details, and a muffled, almost palpable sensibility. The result is perceived as a strange dream in which a solitary eye probes suspect sites. Many of Jasinski’s photographs lend themselves to subjective projection – both his and ours.

Jasinski, as noted above, is not alone in his artistic pursuit. His attraction to ruins and abandoned structures falls within a broad trend that seems to want to be growing in influence in the world of photography in the very late twentieth century. But unlike American Emmet Gowin, for example – whose sensitive photographs have, since the seventies, sounded an alarm over polluted lakes and sites devastated by shut-down nuclear power stations – Jasinski portrays ruins and oblivion poetically. Their intimate character distinguishes them from the industrial archaeology project undertaken in 1959 by German photographers Bernhard and Hilla Becher. Cultivating visual anonymity, their series of water towers, silos, and gas meters is in the current of the so-called objectivity of the scientific inventory – except, perhaps, for the attention paid to the structure of the subjects photographed, and even they are recorded with the greatest possible neutrality.

In fact, Jasinski’s images are not so much testimonies of any particular post-industrial catastrophe but poems that, a little like T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land – without the presence of human beings – bear witness to the sterility of the environment. Erosion and waste are visible, but they serve as a pretext for the emotion that they provoke in the viewers who will live with them for a while. Whether it is the material violence underlying the broken metal rods left behind in a corner of a construction site (Rue des Quatre-Fils Aymon, Bruxelles), the disorienting monumentality of ravaged foundations (Boulevard Émile-Jacqmain, Bruxelles) or the extinguished glory of a voided building draped with tarps and nets (Villa Edelstein. Chemin Rieu, Genève), the door to possible interpretations is wide open.

Having said this, opening a door does not entail crossing the threshold. If one willingly partakes of Jasinski’s dusk-laden offerings and finds oneself staring at them, it is because they lure one in. Jasinski’s main skill is his aesthetic prowess in muffling the striking symbol of his thematic framework. In a way, he dulls the shock. For him, urban decrepitude is revealed to the rhythm of his shots: slowly. This artist makes us wait. He gives us first something to see and then, bit by bit, something to feel. Unlike the Berchers, Jasinski doesn’t fear plays of shadow and light. His photographs are enrobed in effects of depth, relief, and texture. Against impenetrable zones of black are juxtaposed infinitesimal details of branches, sand, and cracked macadam that the moon, and only the moon, illuminates.

Jasinski’s formal prejudice is evident in Ilôt 13. Montbrillant, Genève. Looming over an area – a parking lot or an anonymous asphalt space, perhaps – a couple of corner buildings vie for volumes, geometries, and serial motifs. In the old roughcast wall of one are ghostly silhouettes of long-disappeared, almost identical residences. The other, in a slightly Magrittian style, is embellished with a vertical line of lit-up windows. If the graphic quality of the image is the most important thing here, we can be sure that the purpose is to hold our eye, to let us familiarize ourselves with the site and investigate the crannies of broken stones. Once our eyes are used to the darkness, our imagination enters into play. And in André Jasinski’s photographs, imagination has carte blanche.

André Jasinski lives and works in Brussels, Belgium. For the last ten years, he has had exhibited regularly in Belgium and abroad. In 1995, he was a commissioner ofand exhibitor in La ville et son cliché – Regards croisés Bruxelles-Genève. Most of the photographs presented inthis portfolio originated with that project.

Art critic and journalist Jennifer Couëlle lives and works in Montreal, and she has been publishing pieces on art since 1989. Her writing appears in the magazines Parachute et CVphoto, among others, and in the newspaper Le Devoir.