[Spring 2006]

Arborealis

Thaddeus Holownia

Anchorage Press

2005

The panoramic format in photography simultaneously poses delicate problems and offers sumptuous opportunities. The problems tend to centre around compositional matters – the way that the image, often more than twice as wide as it is high, is usually informed either by a conventional recourse to the divisions of the golden-section or by the plunking of the image’s centre of interest directly in the middle, relegating the rest of the photograph to imagistic adjacency (like an altarpiece with wings). The chief opportunity that panoramicism provides, by contrast, is an opportunity for the photographer to acquire pictorial sublimity, one of the provisions of the sublime being to offer viewers a picture plane wider than their natural angle of vision: a shard of immensity.

New Brunswick photographer Thaddeus Holownia has been working with large-format view-cameras for a quarter of a century now. Although he has made photographs in 8 x 10, 11 x 14 and 12 x 20 inch formats, he seems most fully himself – that is to say, most luxuriantly expressive – working with the panoramic 7 x 17 inch image.

It is this image size that Holownia has chosen for his latest book, a truly opulent work called, very deftly, Arborealis. According to the book’s unsigned afterword – which, given its historical, geographical, and ecological exactitude, is probably written by New Brunswick poet and now professor emeritus at the Nova Scotia Agricultural College, Peter Sanger, who also contributed thirty poems to the enterprise – the photographs making up Arborealis are “set on the northwest coast of Newfoundland in an area defined on highway maps by the long fjord reaches of Bonne Bay. The area is generally known by the name of its highest peak, Gros Morne.” There are thirty-one photographs in this exquisite book – full-size, stochastic duotone contact prints of the 7 x 17 inch negatives that Howlonia made, according to the specifications at the back of the volume, with a Folmer & Schwing Banquet camera made in 1926, and a Wisner Technical Field Camera made in 1999.

This is the third collaboration between Howlonia and Sanger, the first being The Third Hand (1994), a chapbook-catalogue of an exhibition of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century hand tools, held at the Mary E. Black Gallery in Halifax. Their second book, Ironworks (1995), continued the celebration of their mutual interest in old iron tools and other iron artefacts. It consisted of seven platinum prints by Howlonia and seven accompanying poems by Sanger.

The photographs of Arborealis are uniformly lovely. I use the word “lovely” advisedly because, regardless of the elemental lash of the weather – the damp, the raw, the real – that may have prevailed during their making, the photographs possess a certain relentless serenity that is the inevitable product of extreme horizontality (verticality, by contrast, always looks ascensional and transcendental, while diagonals are invariably edgy, kinetic, temporary, and local).

Because they are almost impossible to avoid anyhow, Howlonia makes constant – and intelligent – use of the panoramic photograph’s inevitable compositional proclivities. His best landscape photographs unfurl like scrolls, for example, across the entire vast field of the picture – as in Trout River Gulch 2001 or the two Green Point 2001 rock-face photos. This transcends the compositional problem and is a logical, unassailable use of the picture’s wideness. Less satisfactory – only because they are so conventionally golden-meaned – are the photographs that are constructed as, say, two-thirds cliff to one-third beach, or two-thirds dark cloud to one-third bright sky. One to two. Two to one. And so on.

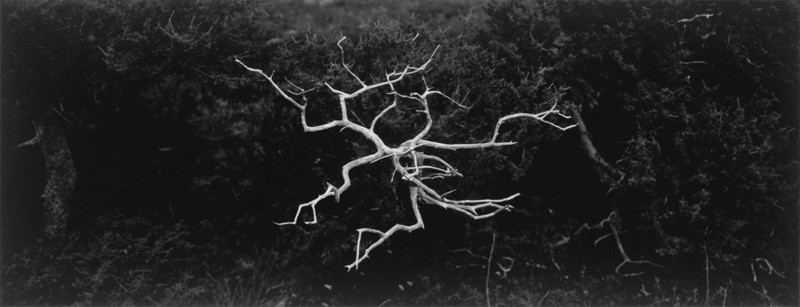

Howlonia seems to perform best when he wields the majesty of the big-screen camera with a almost oxymoronic delicacy (a delicacy that is oxymoronic, that is, given the prodigious largeness of the camera’s means): the finest photos in Arborealis, for me, are those in which the wideness of the camera’s gaze is concentrated on something – often a fine and fragile something – gathered into the middle of the picture. Such is the case, for example, with the ten beautiful Trout River Gulch photographs from 2001 in which Howlonia has isolated dry, gaunt, angular, leafless shrubs, which, glowing as white as bone, claw at the viewer like imploring hands. Placing the chosen subject – in this case, the bare shrubs – at the centre of the photograph is procedurally (paradoxically) the same as allowing the subject to sweep the whole length of the negative. A total sweep of image becomes, photographically, one thing. A centred image, flanked by secondary space, is also, in a manner of speaking, one thing. And these photographic singularities thus gain power by being impervious to division, to distribution, to a parcelling-out along the photograph’s epic length. It was this vivacious oneness (and the ennobling aid of the vertical) that made Howlonia’s stridently vertical panoramic trees of his recent Walden photographs so moving.

Howlonia is very gifted indeed in the showing of multum in parvo – much in little. For me, his photograph of a dry stick (centred and therefore foregrounded) crisping on a bed of pebbles (Trout River Gulch, 2001), one whorl in its long, snake-like length echoing another, bigger one farther along, is the equivalent of a half-dozen of his lowering skies and sweeping shorelines.

Because they are so interrelated, it is probably necessary to say something at this point about the Peter Sanger poems that punctuate and presumably enrich the progress of the photos through the book. As Sanger has pointed out, in an article by Andrew Steeves titled “A Brief History of the Anchorage Press: The First Twenty Years” in the journal of the printing arts called DA (The Devil’s Artisan) for the summer of 2004, “the poems are not linked at every point to a specific photograph. This time [as contrasted with Ironworks], the linkage of text and illustration is oblique.”

Sometimes the meaning of the poems is oblique as well. Sanger is always an absorbing writer, but he tends often to stretch disconcertingly after metaphor (as when he refers to one of Howlonia’s stark branches as an “Uncastable antler whose tines/have locked into stone”) and to alliterate himself into oblivion (“Cars cruise below/ blood-beats booming”). Too often, he reverts to the staccato rapping of lists and disassociated words (“Fel. Temp. Preparatio . . . Stone meal. Stone ground. Magnesium. Nickel, chrome . . .” etc.). Which is okay, I guess, except that the resulting choppiness is very far removed from the slow, dignified fluidity of Howlonia’s pictures.

The book is exceedingly handsome. It has been produced and printed by the Anchorage Press at Jolicure, New Brunswick, which is essentially Howlonia’s own press – though always run as a teaching press for his students at Mount Allison University. The regular edition, 10 x 19 inches and slipcased, is limited to 500 copies and sells for $150.00. There is also a “preferred edition,” limited to 100 copies, fabric-bound and signed by Howlonia and Sanger, which sells for twice that.

Toronto writer, art critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author or co-author of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe and Mail.