[Fall 2007]

by Dayna McLeod

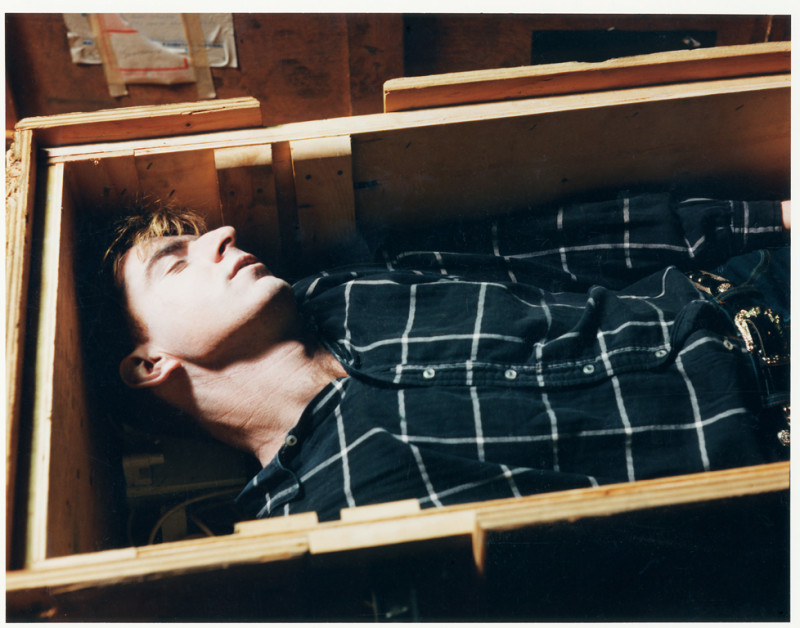

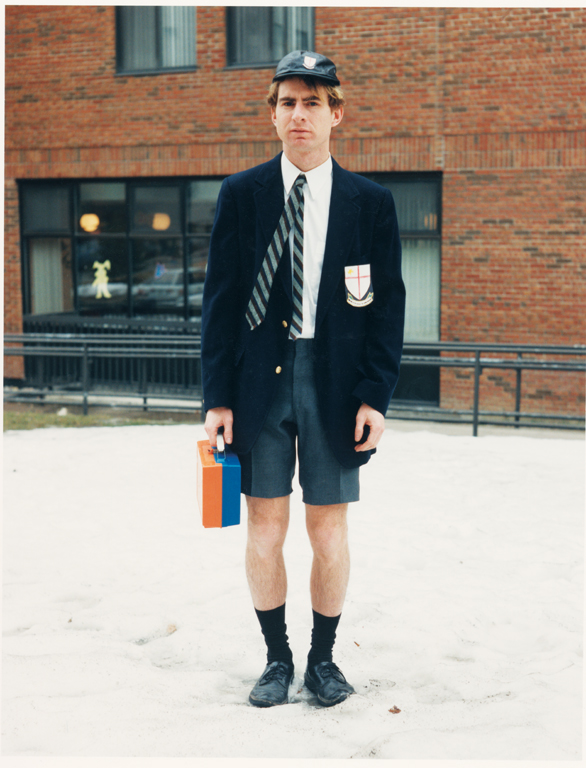

Performative in nature, this series is in fact a selection of images first shown as part of Litherland’s 1993 storytelling performance piece, Souvenirs. In this earlier work, viewers chose an image of Litherland from a table of self-portraits in which he was dressed “as he is, wanted to be, or had lived,” activating him to respond with a short story to “create a poetic juxtaposition with the photograph.”2 This performative drive continues within this pared-down selection of images; however, this time, the responsibility for any narrative is left to the viewer. Binary notions of what are masculine/feminine, submissive/dominant, and passive/aggressive are put into a blender and served up for the viewer after being passed under a microscope, but whether this microscope is the viewer’s or Litherland’s to share is in question. His self-portraits nudge us to search our own baggage for personal alarms, bombshells, and other incendiary devices that may actually be disguised forms of theoretical discourse, political correctness, or voyeuristic projection – all set to go off at any moment.

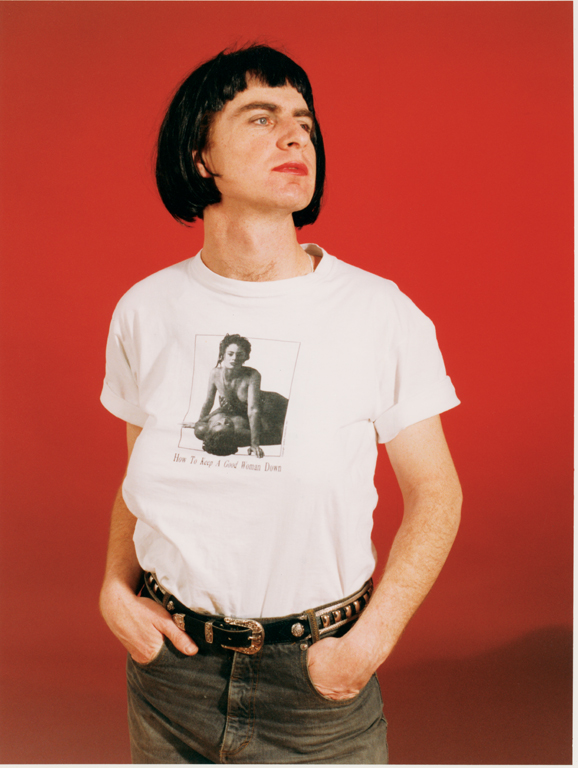

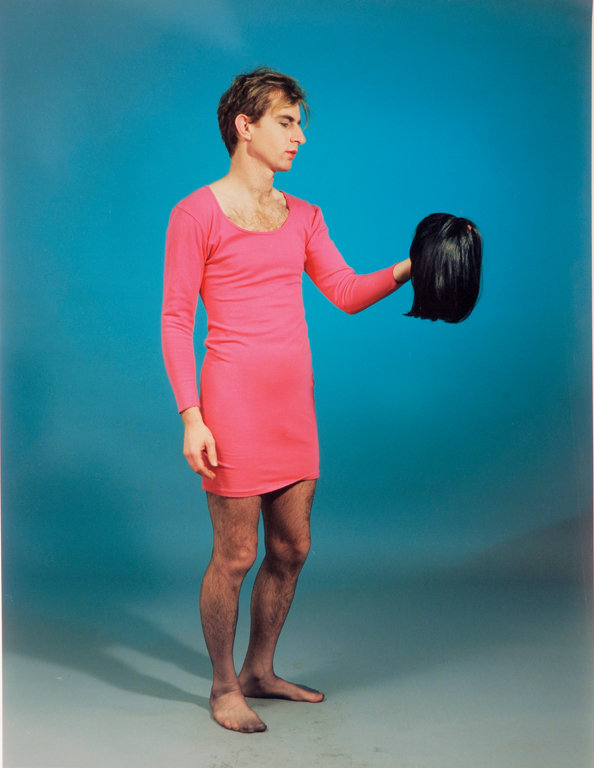

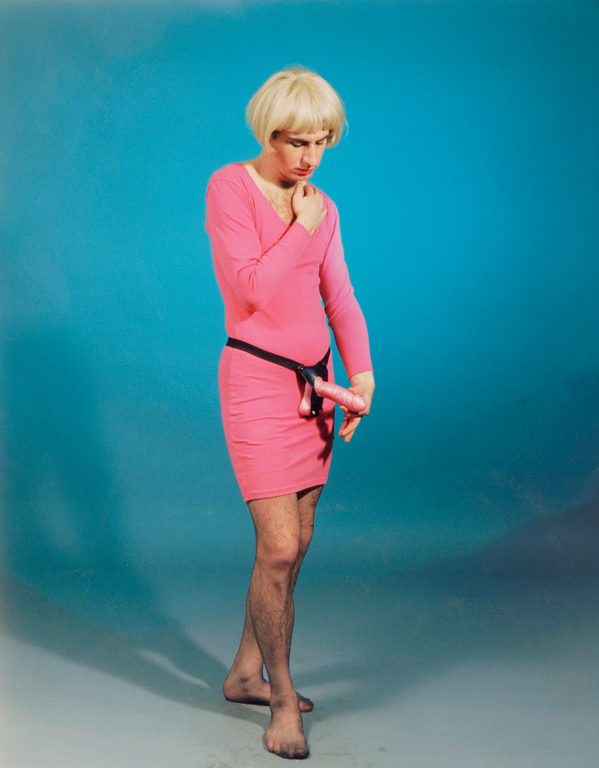

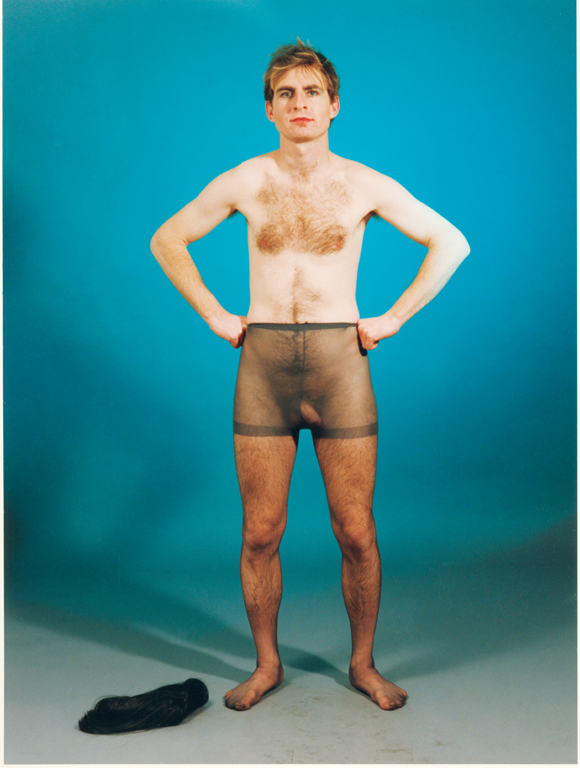

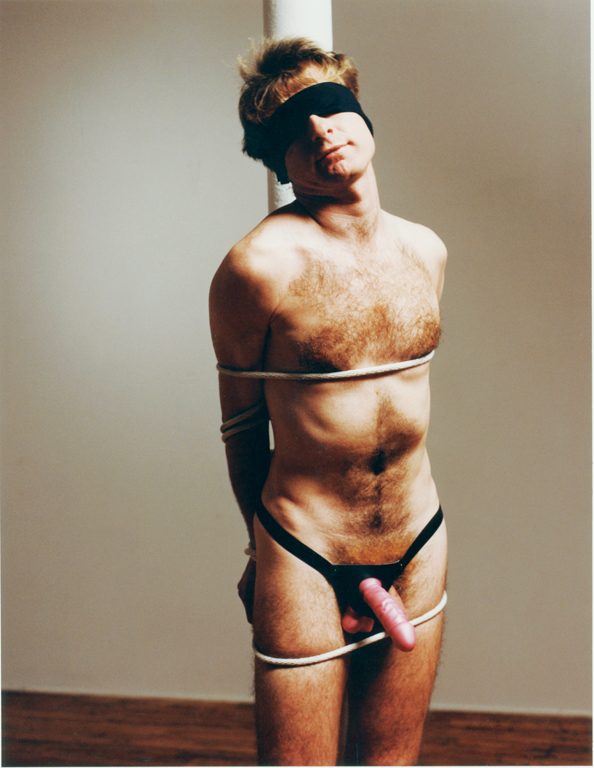

With face made up, Litherland stands hairy-legged in stocking feet, passively posing in the five portraits that are grouped together within this series. In each image, Litherland poses with a single accessory: cigarette, strap-on, make-up mirror, or wig. These props accentuate Litherland’s feminine performativity despite his unpadded flat chest and the authentic crotch bulge beneath his clinging pink dress. He seduces us with his eyes in “Cigarette”; he smiles unabashedly into his mirror with his back turned to us in “Mirror Boy”; he confronts us with an unsmiling full-on stare in “Conqueror” – naked except for the transparent pantyhose that covers his hairy legs and flaccid penis. At first glance, it may seem that he dons feminine signifiers while maintaining a masculine base to “subvert overly restrictive heteropatriarchal sexual scripts;”3 that he is purposely letting his masculine slip show in his feminine performativity to ultimately challenge the viewer’s preconceived notions of what constitutes femininity and masculinity through his use of (in)complete drag. Appropriating these (feminine) signifiers, Litherland uses them against us: challenging us as viewers and consumers of cultural, feminist, queer, and trans theory about our own reservations of binary sexual codes. He confronts us with semi-transformational representations, but there is something else going on here; there is something else in play. There is a focus on communicating the personal in public, of getting the viewer to see a bigger picture of the artist that exposes an awkward, honest vulnerability that is underscored by quiet humour.

“Hamlet” features Litherland’s pink-clad she-male holding a black wig, true to her Shakespearean namesake, yet sidesteps a potentially tragic reading of this portrait quintet with humour that relies on the viewer’s familiarity with the infamous Prince of Denmark. This naming and action reaches past divisive gender politics, theoretical rhetoric, and any biases that the viewer may bring to their reading – humanizing Litherland’s Hamlet while allowing her to pose problematic questions about identity, gender, and representation. Similarly, “Diesel Queen,” an image that in name alone is an obvious play on queer culture labelling, makes Litherland’s self-portrait a Lesbian-Gay-Bi-Transsexual hybrid that combines lipstick lesbian fashion savvy, Diesel Dyke bra-less-ness, and other stereotypical signifiers of queer culture to create an improbable construction that indulges our general mainstream view of lesbianism.

This queer culture quoting continues in “Bigger Than Life” and “Tied Up,” in which Litherland reveals the gendered power of the phallus. “Bigger Than Life” features his pink-clad he-she in a blond wig and erect pink strap-on over her dress, gazing down at her phallus with a passively contemplative look on her face. Seemingly empowering because his performative femininity trumps his own masculinity, the strap-on represents a borrowed masculinity for Litherland’s female subject. However, in “Tied Up” the semiotics of the strap-on are complicated by its now emasculating potency. Here, Litherland is blindfolded, naked, and tied to a pole in a St. Sebastian pose wearing the same pink strap-on. But in the math of strict binary gender codes, in which heterosexual masculinity is defined by what it is not – that is, “not being compliant, dependent, or submissive,” “not feminine and not homosexual,”4 “being not-female”5 – the act of adding borrowed masculinity to existing masculinity implies that the original masculinity is somehow lacking, less than, or impotent – negatively impacting on the heterosexual male subject.

However, these strict gender codes start to fall apart within the series, as do queer codes of straight males performing queerness, as viewers recognize that they are surrounded by Litherland’s feminine/masculine personas, a recognition that, in turn, contributes to the deconstruction of other hegemonic binary systems for viewers. Here, Litherland illustrates “the boundary between queer and heterosexual as permeable and blurry” while “breaking down the assumed association between male femininity (or the absence of masculinity) and homosexuality, further challenging commonly accepted beliefs”6 of what constitutes heterosexual masculinity. He is subverting heteronormality – not inverting gender, but constructing portraits of his own that are imbued with his own personality, fragility, and fantasy. He does not simply put on a disguise and create a caricature; he thoughtfully forms character. There is an earnest vulnerability here that challenges our biases and political correctness. Litherland sidesteps his “right” to ask these questions, to subvert his own masculinity, simply because he is a heterosexual white male artist.

Litherland challenges the viewers to explore their biases as much as he explores the boundaries of his own masculine/feminine identities by attempting to disrupt traditional heterosocial binary codes, and by “highlighting the artifice of gender and denaturalizing the association between man and masculinity and women and femininity.”7 “Masculine” portraits within this series and context borrow narratives from the surrounding images and provide the viewer with a multi-faceted portrait of the artist, as do the “masculine” portraits of him dressed in motorcycle and skydiving wear in the original series, Souvenirs. Further confusing the readings of these portraits is how feminized heterosexual masculinity has changed the way we see gender construction and, in turn, the way we now view Litherland’s work. His penchant for gender play and self-portraiture reveals his intention of communicating difference complicated by awkward questions and vulnerability.

Feminist, cultural, queer, and trans politics have evolved since 1993, when Souvenirs was originally performed, and likewise, the theoretical baggage that we carry with us now has changed, charging the Absolutely Fabulous collection with a new vigour. Teasing us with binary signifiers, Litherland dares us to acknowledge our subjective biases while infusing a quiet humour into the work, leaving us to question the theoretical structures in which we choose to live, and the codes by which we think.

2 Paul Litherland, “Souvenirs Index”, paullitherland.com, (09/01/2007).

3. Hill, Darryl B. (2006). “‘Feminine’ Heterosexual Men: Subverting Heteropatriarchal Sexual Scripts?”. The Journal of Men’s Studies, Vol 14, No. 2, Spring 2006, 145-159.

4 Herek, G.M. (1987). “On Heterosexual masculinity: Some psychical consequences of the social construction of gender and sexuality”. M.S. Kimmel (Ed.), Changing Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity (68-82). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

5 Bird, Sharon B. (1996). “Welcome to the Men’s Club: Homo-sociality and the Maintenance of Hegemonic Masculinity”. Gender & Society, Vol 10, No. 2, April 1996, 120-132.

6 Hill, Darryl B. (2006). “‘Feminine’ Heterosexual Men,” p154.

7 Shaw, Deborah (2000). “Men in High Heels: The Feminine Man and Performance of Femininity in Tacones lejanos by Pedro Almodóvar”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies, Vol 6, No. 1, 2000, 55-62.

Paul Litherland studied photography and fine art at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in Vancouver. He moved to Montreal in 1988 and graduated from Concordia University with an MFA in photography in 1994. In 2006, he participated in an artist residency in Mexico City and performed at the Rencontre internationale d’art performance in Quebec city. He will be showing photographic work from the series Art Photography at Gallery 44 in 2007. He is represented by Galerie Thérèse Dion, Montreal. www.paullitherland.com

Dayna McLeod is a freelance writer and video and performance artist. She has written extensively on art, and her videos have played internationally. She has just received a grant from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec for an animation series that examines the iconography of the vagina dentata legend in a modern context.