[Fall 2013]

Images are connected to our physical environments more dramatically than ever before – literally opening up new spaces of interactivity and connection that transform the experience of being in the city, its semiotic forms, and its modes of public gathering, navigation, and movement. ValéLrie November, Eduardo Camacho-Hübner, and Bruno Latour have argued, “The common experience of using digital maps on the screen, and no longer on paper, has vastly extended the meaning of the word navigation.”1 Indeed, these authors provide us with a definition of the new GPS-enabled real-time cartographic environments that describe a new experience of territoriality in urban spaces. Importantly, they differentiate between mimetic and navigational systems, offering an explanation for why the cartographic is such an important term for sense making in the city. They emphasize the new flexibility of forms of navigation that enable users to shift seamlessly between 2D and 3D interfaces, between the local detail and the macro view of the territory and the planet found in Google Earth. Urban screens, mobile media, digital mappings – ambient and pervasive media of all kinds – create ecologies in which entire communities dwell or in which singular entities take refuge. They also create layers of simultaneous temporalities and networks of histories that coexist in one place.

A new generation of artists are using media technologies to explore these interfaces and the meanings of translocality, public spaces, and mobile networks that are distinct configurations grounded in place – indeed, often several places and several times at once. How do such art practices function as forms of public art and in site-specific settings while serving as a tool for enhancing communication and forms of media art?

The ways in which the cartographic has moved beyond mere two-dimensional representations toward constructed, dynamic, and layered spaces is explored in an upcoming exhibition, Land/Slide: Possible Futures (21 September to 13 October 2013).2 The organizers of the exhibition have invited thirty artists working in a variety of media (from sculpture to data visualization) to transform and reimagine a heritage village at the Markham Museum in the Greater Toronto Area. The artists have been asked to reinterpret over thirty pioneer houses built between 1820 and 1930, as well as eight thousand historical artefacts, in the context of climate change and a world in transition. Working with digitized diaries, 3D projections, augmented reality (AR), and other media, participants are proposing new histories and new futures for the use of land. This is an example of a contemporary form of public space that uses museums and archives, often seen as static and “dead,” to create dynamic simultaneous temporalities and invite participation by the public.

This approach to animating archives and collections can be seen in recent art approaches to archives. For example, the exhibition Archival Dialogues: Reading the Black Star Collection, the inaugural exhibition of the Ryerson Image Centre in 2012 curated by Peggy Gale and Doina Popesku, invited eight artists to engage with Ryerson’s Black Star photographic collection. In his TAUT, Michael Snow projects photographs of crowd scenes (demonstrations, riots, and protests) over a classroom furnished with tables and desks wrapped in white paper. The artist’s white-gloved hands hold photographs up one by one. The projected image is broken up by the physical space, fragmented across the architecture of the classroom, as the process of reading images is materialized. Thus, the still photographs of urban crowds that have been locked away for so long are reanimated by the video of the artist/archivist presenting them to us. Indeed, these moving images constitute pedagogical moments in which the archive is activated through the different digital and physical interfaces.

Similarly, in April 2013, artists David Colangelo and Patricio Davila produced a massive projection on the Archives of Ontario building at York University. In 30 moons many hands, it appears as if hands are reaching into the building and bringing forth various images from the archives for inspection. The images that emerge begin to tell the story of the Canadian adventurer Douglas Carr, who, in the late 1930s, traversed Europe and Africa by bicycle, a journey that he documented extensively through photography and film and that lasted, in his words, for “thirty moons.” The new availability of large-scale projectors and image-mapping informatics, along with the new attitudes of archivists who are valuing public access to images as equal in importance to their preservation, is encouraging the active participation by the public in the rereading of historical artefacts.

It was in the spirit of this openness that the director of the Markham Museum, Cathy Molloy, agreed to open the museum’s archive to the thirty artists in Land/Slide. The role of digital media is central to the exhibition, as the entire site will be enhanced with projections, audio walks, and an AR app that opens the archive, including previous cartographies that had long since vanished in this new, “levelled” (sub)urban space. What is changing in this iteration of urban space and temporal space is the interface among the built environment, the viewer, and the image. Canadian artists Jennie Suddick and Camille Turner have designed a se- ries of guided audio walks through Markham that exhibition goers will be invited to download onto their smart phones. Suddick is interested in generational differences and has interviewed “old-timers” and a younger generation of Markham dwellers about the walks that they remember or like to take. Camille Turner is researching the history of black people in Markham and the slave trade in Ontario, narratives that she locates in the twenty-five-acre landscape of the museum’s property. Turner’s walk will be directed by AR markers embedded on buildings and geographical elements of the site. Filmmaker Philip Hoffman’s installation will be situated in the slaughterhouse on the museum grounds and will recall his years of working for the family business, Hoffman Meats in Kitchener, Ontario. He presents a series of small-scale projections visible only through the exterior of the building; viewers will peer through the holes in the barn board and witness scenes from the past. The tiny images that he is working with are made possible through small projectors that he is embedding in the wood and through small cameras such as the Go Pro, which can penetrate the building’s nooks and crannies. His installation tells the story of the massive industrialization of the meat industry in Canada, a hidden history of carnage. The small and large images, like the audio projects, feature the flexibility and portability made possible through advances in digital imaging and projection.

In July 2012, Markham became one of Canada’s newest cities – previously a suburb located twenty minutes north of Toronto – with a population of over 300,000 and growing. It claims to be Canada’s hi-tech capital, as there are a number of large companies in the area, such as IBM, Motorola, Toshiba, Lucent, Honeywell, and Apple. It is also the most demographically diverse municipality in Canada, with East and South Asian residents (many of them newly arrived immigrants) making up more than 65 percent of the population. Land/Slide is concerned not only with different interpretations of history but also with the different interpretations and memories of landscape that this ethnic diversity represents, and with the different possibilities for ecological and social sustainability that these hold. Markham serves as a case study through which to develop a community conversation and critical reflection on the future of land use in Toronto’s outer municipalities. What is the future of development in one of the fastest-growing regions in North America, the exhibition asks, and what impact will such development have on our shared sense of what land means in terms of food, ecology, and the inherent value of nature?

Internationally acclaimed Chinese artist Xu Tan is featured in Land/Slide. Xu has been carrying out a residency in Markham for the past several months and is seeking to understand the Chinese diaspora living there. He is curating his own Chinese pavilion featuring members of the Chinese community – Elvis impersonators, immigration consultants, chefs, and people who have created not-for-profit organizations to help newcomers acclimatize to their new environment. The pavilion will be an architecturally stunning structure to reflect this cultural specificity of Markham; audio and video interviews will be downloadable through the AR app designed for the exhibition.

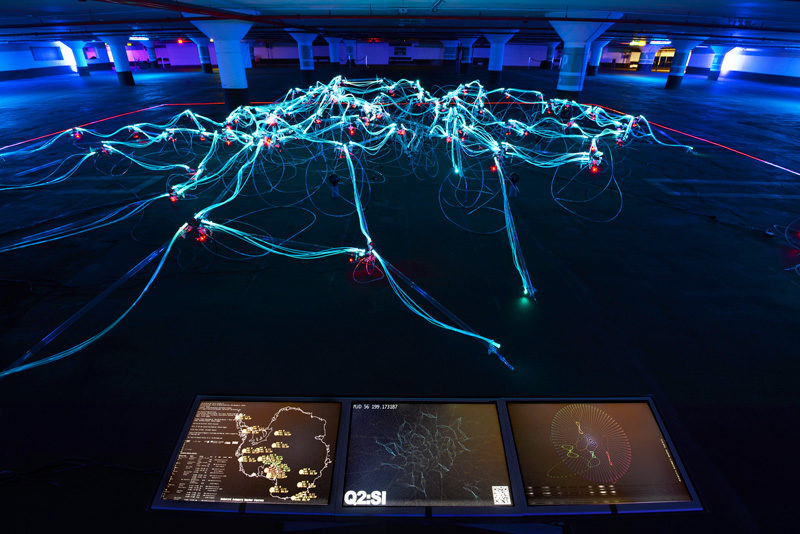

Computer programmer and artist Mark David Hosale is working with the Los Angeles architect Jean-Michel Crettaz to create Quasar 4.0, a massive, web-like sound and light sculpture some eighty feet long; it will sit in the museum’s gallery at the centre of the exhibition. The sculpture is made up of an array of crystalline elements and fibre-optic strands, which are supported by an intricate metallic substructure inspired by quantum loops. Resembling an octopus, it is an advanced composite of systems that measures and processes information from three different sources. First is the body heat of viewers in the gallery, which will form an interactive base that activates sound and colour aspects of the structure. Second is meteorological information from three weather stations in the Antarctic, which includes data streams and observations from the year prior to the exhibition. Third is geological information that cartographers have been extracting from the nearby 1.8 million hectares of protected greenbelt land in southern Ontario – the largest greenbelt in the world and one of the most innovative strategies for combating the effects of climate change. Connected to the sculpture is a triptych of screens that provide tangible information (descriptions, maps, photographs, visualizations) that feeds into the Quasar 4.0 archival network, where past and future come together.

Indeed, this exhibition transforms the museum into a robust network – one that is not simply about safeguarding the past behind glass vitrines for passive viewers to look at. Land/Slide: possible futures will open a gateway between past and future. It will create a space of multiple interactions between virtual and real cartographies – from the micrological elements of located stories of migration and indigenous voices to cosmological visualizations of geological data that tell us about our planet in transition.

1 Valérie November, Eduardo Camacho-Hübner, and Bruno Latour, “Entering a Risky Territory: Space in the Age of Digital Navigation,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28 (2010): 586.2 www.landslide-possiblefutures.com.

Janine Marchessault is a Canada Research Chair in Art, Digital Media and Globalization at York University in Toronto. She is the director of the Visible City Project at York University, which is examining urban art cultures in the twenty-first century city. She is the author of McLuhan: Cosmic Media (Sage, 2005) and co-editor of Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema (UTP, 2007). In 2009, she co-curated the Leona Drive Project, a site specific exhibition in six vacant 1940s bungalows in Willowdale, Ontario. She was co-curator of the 2012 Toronto Nuit Blanche monumental project, “Museum for the End of the World,” at Nathan Phillips Square in Toronto. Her latest project is Land/Slide: Possible Futures, a multi-sector site-specific exhibition that brings together over thirty artists to look at future land uses in one of Canada’s fastest-growing regions. She recently received the Trudeau Fellowship to support her research and curatorial practices in the area of public art and civic cultures.