[Summer 2009]

Relevance is a word that permeates discussions about the role of museums within the social fabric of community. As repositories, museums have a primary function of cultivation not only of objects but also of a public to engage with them. Museums amass, describe, preserve, and, ultimately, display facets of their contents, arranged and presented in ways designed to prompt interconnections between viewers and a story. The tale being told in this manner can be understood as a trajectory punctuated by places to look and to think. Within such experiential encounters, an institution hopes to say something new, to underscore its particular point of view, or to shatter mythologies, all the while striving to inspire reactions and responses that, in turn, create return visits.

by Johanna Mizgala

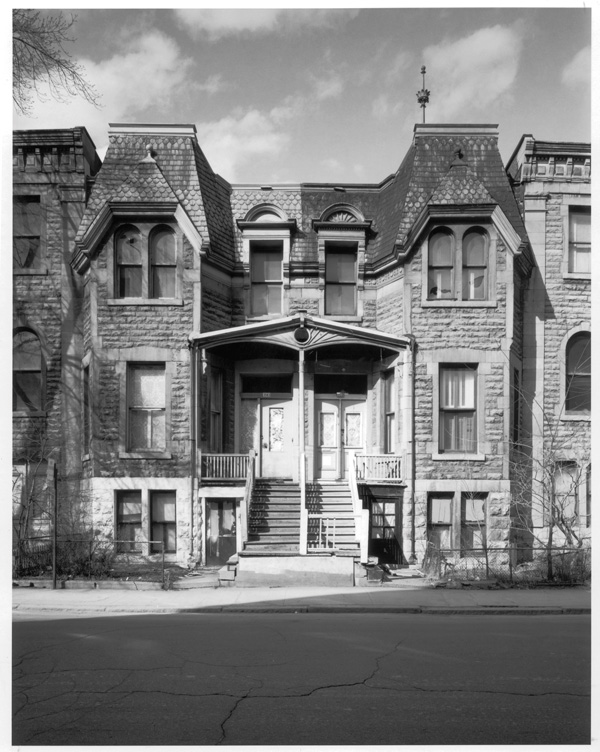

At the heart of the McCord Museum’s collection rests a desire to tap in to a collective memory that reflects the history of the city of Montreal; the McCord’s objects and images serve to quantify and qualify some of the numerous experiences of the historical and contemporary communities and cultures that coexist, intermingle, and diverge throughout an ever-changing urban landscape. Fixing such an iconic place is a task altogether intoxicating in its impossibility, for just as any given landmark, green space, or street corner is undeniably and indelibly emblematic of the city at a particular moment in time, perspectives on these places cannot be set in stone. Instead, impressions are imbued with a capacity to shift as places and faces are seen anew or through new eyes. In this way, the city’s commonalities are as countless as its changes through recollections and lived experience, not to mention the layers and traces that are lost and found through the ebb and flow of its constant and inevitable deterioration and renewal.

The focal point of the Museum’s collection is the Notman Photographic Archives, composed of over one million photographs, including some 450,000 photographs and negatives taken by the Notman Studio itself, which was in existence for over seventy-eight years. William Notman (1826–91) built a thirty-five-year career as a photographer in Montreal; he also established some seven other studios in Canada, as well as several interim studios at colleges and universities in the northeast United States, photographing the scholastic set during the academic year. It was the largest photographic business in North America, offering a range of portrait options to patrons from all socio-economic strata. The Notman name continued to be synonymous with studio portraiture long after William Notman’s death and well into the twentieth century; his son Charles eventually sold the family business and retired in 1935.

In addition to the Notman material, the Photographic Archives also holds a wide range of photographs taken by practitioners such as Alexander Henderson, Benjamin Baltzly, and William Topley, as well as a host of intimate and candid images by amateur photographers and unidentified artists. The Photographic Archives offers a glimpse into the lived experience not only of Montreal and its citizens, but also, by extension, of places and faces from other parts of Quebec and Canada, from the earliest days of photography to the present. An accumulation of everyday life – portraits of Montreal society as well as random and anonymous faces – collectively, the Photographic Archives represents the passage of time through a multitude of marked occasions, mundane activities, celebrations, and sombre obligations, as well giving visual evidence to the growth and development of the economic, political, and social landscape of the city. While photographs fix the past in a figurative and literal sense, with each viewer comes a new appreciation of the work through their own lens of sensibilities, as photographs “mean” different things with each successive experience. It is the layering of reception that produces the richest encounters, in the same way that well-travelled streets can yield unexpected turns and startling discoveries.

Responding to an institutional desire to attract new audiences and to bring the collection out of the vaults and into a wider sphere of circulation, the McCord Museum presented three interconnected installations of large-scale reproductions, shown along the sidewalk of McGill College Avenue in downtown Montreal, over three successive summer and fall seasons. The images were mounted in large aluminum brackets, in a manner similar to advertisements or neighbourhood maps that a passerby might view. With images from the collection presented in this way, as opposed to a more conventional exhibition within the Museum’s walls, the viewer’s imagination was enlivened through the possibilities of happenstance. In the course of their own everyday lives, people were free to wander in and out of the collection for a moment, as if they were daydreaming while glimpsing a poster on the Metro platform or window-shopping on the way home from work.

Responding to an institutional desire to attract new audiences and to bring the collection out of the vaults and into a wider sphere of circulation

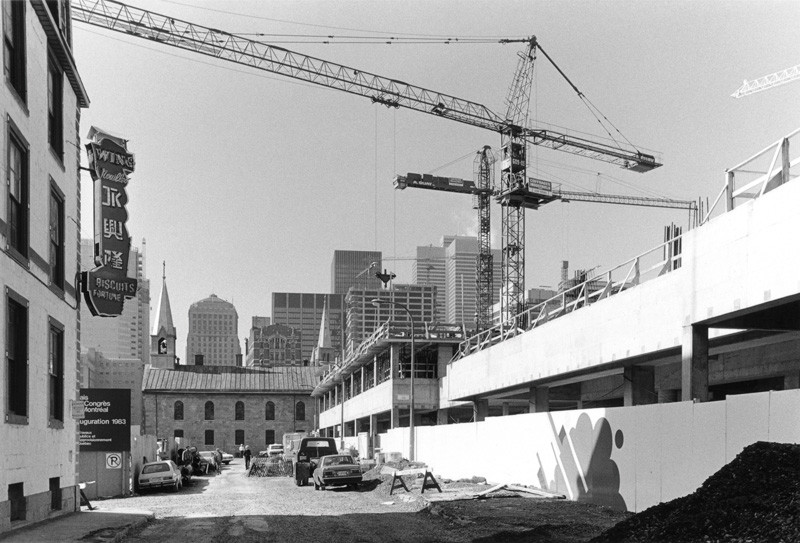

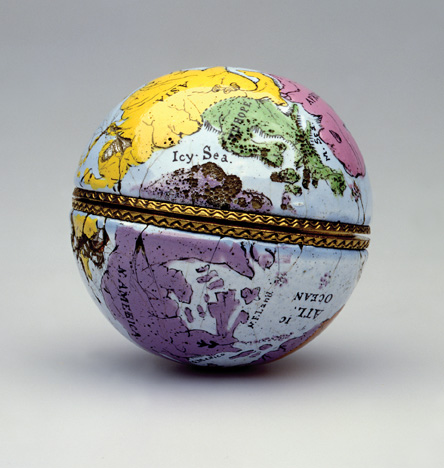

The first installation, Transactions, proposed juxtapositions of detail colour views of objects held in the collection with reproductions of black-and-white photographs from the Notman Archives. Using the metaphor of the social and economic permutations of exchange, the twenty-eight pairs of images in the installation posit connections between material culture and photographs of Montreal life. Transactions enabled the Museum to showcase pieces, albeit in a reproduced format, that might seldom be seen due to their fragility or some other consideration precluding long-term display. Objects were chosen in part for their affinity to the archival photograph in question, such as the pairing of an antique machine for making cheques with a photograph of office workers who might have employed such a device (William Notman and Son, 1903). Enlarged to monumental scale and presented outdoors, other gems from the collection, such as an exquisite nineteenth-century ceramic and enamel snuffbox in the shape of a globe, shown here with a view of the Montreal harbour (William Notman and Son, 1884), could be exhaustively examined and appreciated in a way altogether impossible in a traditional exhibition format.

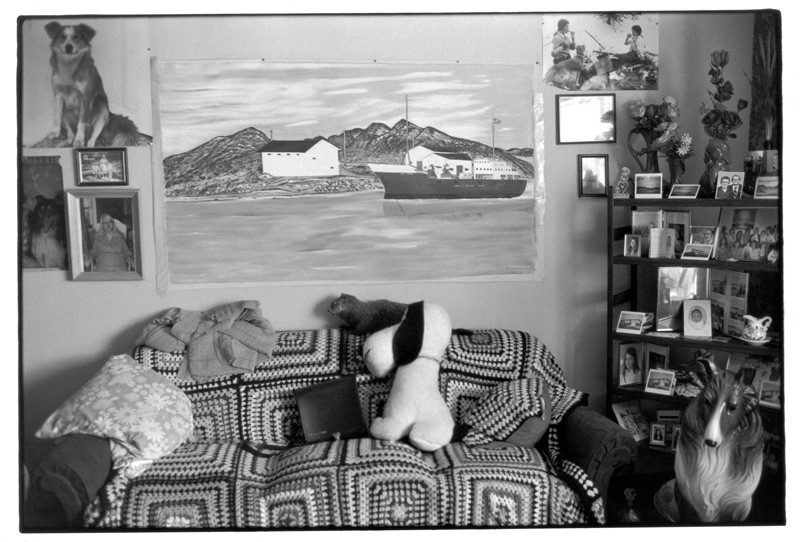

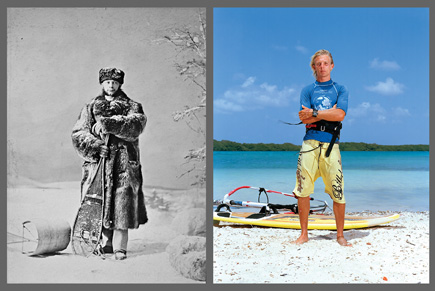

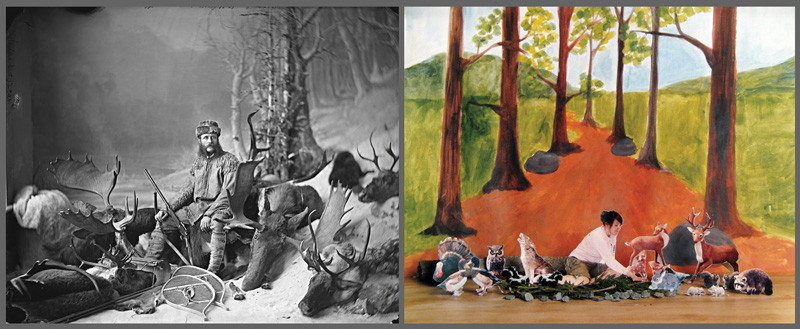

Last summer, the McCord presented the third and final incarnation of its outdoor installations, Inspirations, aptly titled in that it was perhaps the most lyrical of the three shows. In this offering on the street, new photography by students from the Concordia University Studio Arts Department was featured alongside the historical photographs. Just as in the earlier versions of the project, pairs of photographs were linked for points of resonance, whether for their visual affinity, such as the body lines of the figures in Edward Walter Roper’s photograph Under the Green Arbour (1901) and in Shannon Lucky’s Apartment Dweller (2008), or some other point of verisimilitude, such as the replicated outdoors in William Notman’s portrait of Campbell McNab and his hunting trophies (1873) and Christine McNabb and Animal Friends (2007) by Zoe Yuristy. When the historical images were brought together with contemporary work, the viewer was asked to consider the Notman Archives’ photographs not only as portraits in their own right but also for their capacity to provoke creative responses by other photographers. Moreover, in these echoed images of Montreal and the people who inhabit its places, this installation not only offers a glimpse into what the city once was, but also hints at what it will has become.

Together, the McCord’s three installations brought the museum’s collection out onto the street in a large-scale format that possessed the kind of dynamism typically associated with advertising billboards or street art. By mounting an exhibition that underscored the connections between the faces and places of Montreal’s past and present and its local and urban environments, while simultaneously being easily accessible and visually engaging, the museum was able to reach audiences that may not have taken the time to come through its doors. In bringing new viewers into dialogue with the archival photographs, it may, in turn, foster additional points of interrogation and association. Ultimately, it may yet achieve that elusive measure of relevance.

Johanna Mizgala is a curator and critic based in Ottawa. Her most recent preoccupation is an investigation of the occurrence of humour in early studio portraiture and how such flashes of personality appear to transcend distinctions of race, class, and gender.