par Zoë Tousignant

I have been reading Ciel variable since 1996. A while ago, its editor-in-chief, Jacques Doyon, asked me to write an essay, destined for the Archives section of the magazine’s website, that would demonstrate “the importance of the magazine as a medium and space of exploration for photography.” And so, over the past few weeks, I have been re-reading Ciel variable back to back, from issue 1 to issue 99. Having previously undertaken the exercise with other periodicals, I knew that this research process had the potential to reveal another perspective on Ciel variable. Treating a magazine as an object of methodical study gives one a bird’s-eye view of its character and history. From this inclusive vantage point, one can see patterns and mutations more clearly. It is a way of reading that runs counter to the essentially ephemeral nature of magazines, which are intended as mirror reflections of particular moments in time. Their mode of address is largely in the present tense: readers are told and asked to think about issues and events relevant to the now. Yet, through a global reading, present-tense utterances become historical.

Magazines are regularly injected with what I would call “signs of self-consciousness,” passages in which the identity and purpose of the publication are reiterated. It is as though, faced with the constant threat of dissolution, magazines need to repeatedly justify their own existence. (The periodical business, like the periodical itself, is built on shifting ground.) Each justification is never exactly identical to the previous one, however, so it is from them that the evolving shape of a magazine can be deduced. A prime location for such declarations is the editorial page, but they can also be found in the credits, the contents page, subscription notices – even in the very name, for magazines frequently change titles and subtitles. Less overt self-definitions can also be detected in the actual content – in the texts and images that a periodical chooses, out of an infinity of possibilities, to publish.

From a reading of the complete run of Ciel variable emerges a continuous yet developing statement about the nature of photography as an art form and the role of the magazine as a vehicle for this art form. In the absence of sustained support for local photographic publishing, its ninety-nine issues, published from 1986 to the present, constitute an account of almost thirty years of photographic practice in Quebec and Canada, a comprehensive (and unique) document of photographic history as it was unfolding. At the risk of oversimplifying the work of many different individuals, it is possible to discern a qualitative shift halfway through Ciel variable’s three decades of publication. Broadly speaking, the year 2000 marks the beginning of the magazine’s transformation from tool of dissemination to medium of creation, a switch that reflects both local institutional changes and international currents in photography.

The Magazine as a Tool of Dissemination

During the first fifteen years of Ciel variable, the magazine was a kind of battleground – a site where recognition of the practice and history of photography made in Quebec and Canada was actively defended. Co-founded by Marcel Blouin and Hélène Monette, it was dedicated to exploring social causes through texts and documentary photography. Each issue used photographs to investigate a given theme, such as culture, family, the city, or power. The publication of extended portfolios was instituted in issue 20 (Fall 1992). Before this, contributors were numerous and images acted like individual, one-word statements.

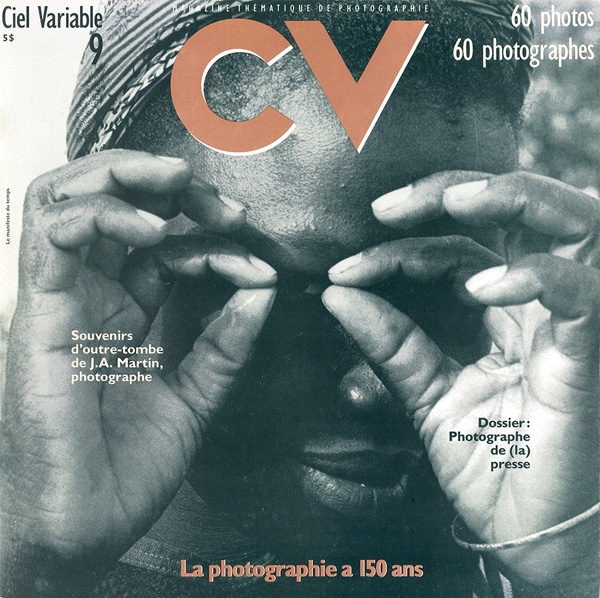

A conception of the magazine as an agent of photographic history is already evident in issue 9 (September 1989), which commemorated the 150th anniversary of photography’s birth. That fall also saw the first edition of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, an event announced in the magazine by a one-page advertisement identifying September 1989 as “a climax of photographic effervescence on a scale never before seen in Montreal.” The ad was illustrated by a photograph of 4060 Boulevard Saint-Laurent, the headquarters of Vox Populi.1 The impact of this organization – which initiated Le Mois de la Photo, La Galerie VOX, and Ciel variable – on the institutionalization of photography in Quebec cannot be overstated. Rallied by the historical consciousness and spirit of celebration inspired worldwide by photography’s sesquicentennial, the people at Vox Populi made it their mission to diversify the ways in which Quebec and Canadian photography were disseminated. The tactic was a multi-fronted onslaught, and Ciel variable was the organization’s publishing arm.

The role of Ciel variable as a key element in the construction of photographic history would be reinforced over the next few years, especially once extended photographic portfolios became central to its form. Writing in issue 21 (Winter 1992), Blouin, who then co-edited the magazine with Robert Legendre, reiterated the “importance and necessity of diversifying the means of dissemination” and the “importance of the print publication, of the trace (the trace of a photographic trace).”2 Despite the major strain caused by continual funding cuts brought on by the 1990s recession, Legendre could still affirm, in issue 29 (Winter 1994), “In the long term, we believe that we are establishing, with the most modest of means, an anthology of Quebec and Canadian photography that provides an accurate overview of contemporary photographic production in this country.”3

As the magazine, Le Mois de la Photo, and La Galerie VOX continued unabated (eventually becoming autonomous institutions), other ways of disseminating photography were added. The launch of Le Musée virtuel de la photographie québécoise, a database available on CD-ROM produced by Vox Populi, was advertised in issue 32 (Fall 1995), as was an exhibition shown as part of Le Mois de la Photo, mounted by Les Productions Ciel Variable, on photography magazines (it was promoted as “the exhibition you can consult”). The same issue includes an essay by Marie-Josée Jean previewing a conference that would investigate the presence of photography in Canadian museum collections.4 The point (and outcome) of this multiplication of interconnected outlets for photography was the medium’s steady, rhizomatic institutionalization. At the centre of the strategy was the idea that for a thriving local photographic culture to exist, the medium needed to have its own institutions. Or so the issue was expounded by Jean, who, in her preview article, posed these burning questions: “Should we focus on this medium’s specific qualities, or should we view it through the prism of its eclecticism? . . . Should we, in Quebec, create a new institution within which to gather Quebec photographic production?”5 The latter question would be answered implicitly in the affirmative in the following years by editor-in-chief Franck Michel. Taking, in issue 41 (Winter 1997–98), the recent scrapping of the position of curator of photography at the Musée du Québec as a sign of the lack of institutional recognition for photography in Quebec, Michel pleaded, indignantly, “How can our museums treat photography, which has a preponderant role in contemporary and modern art, so lightly?”6

The tone was to become more optimistic in the final months of the century, when the magazine offered a review of the wealth of photographic art produced – and disseminated by Ciel variable – since the 1980s. While the fight had not entirely been won at the institutional level, evidence of the centrality of photography in contemporary art practice was rampant. The last number of the millennium, issue 48 (Fall 1999), included essays on Quebec photography in the 1990s by Martha Langford and Mona Hakim that served to obliterate any remaining doubt as to the medium’s contemporary artistic significance.

The Magazine as a Medium of Creation

The year 2000 signalled the start of Ciel variable’s institutional autonomy, the beginning of Jacques Doyon’s tenure as editor-in-chief, and a gradual move away from the conception of the magazine as a kind of “carrier.” Whereas in its first fifteen years Ciel variable was seen as one among several modes of dissemination and promotion of photography, its subsequent fifteen have demonstrated an increasing awareness of the magazine’s impact as an author of photographic history. It is as though the rush of historical awareness brought about by the new millennium – much like the 150th anniversary of photography – heightened the consciousness that the magazine’s producers had of the constructive role Ciel variable itself could play. No longer conceived as an ongoing anthology of contemporary photographic practice – as a representation of something existing outside itself – Ciel variable seems now to be understood as a space in which the writing of history happens.

This heightened state has been accompanied by an expanded definition of photography: reflecting international developments in both photographic studies and art (and perhaps heeding Marie-Josée Jean’s earlier thoughts on the eclecticism of the medium), the magazine has been publishing content that has widened the scope of the photographic to include digital and media imagery, vernacular objects, and archival and collecting practices. An interest in archives, for example, can already be seen in issue 59 (November 2002), a number showcasing portfolios that explore the subject and including an essay by Anne Bénichou on the aesthetic of the archive in contemporary art. Since the turn of the century, a form of historical consciousness has been present in the very images published in the magazine. The early 2000s were also pivotal because of the impact that photographic and video imagery had on the experience of the events of 9/11, a question that Doyon discusses in his editorial essay for issue 55 (Fall 2001), titled “The Shattering Image.”7 Since then, the notion that one can watch history unfold in the present has become almost commonplace.

Issues 77 (Winter 2007) and 78 (Spring 2008) were a two-part celebration of Ciel variable’s twentieth anniversary. Here, the heightened self-consciousness is overt, since one of the forms taken by the celebration was reproduction of all the covers, from issue 1 to issue 76. Reproducing the magazine within the magazine is not an unusual practice in the periodical business, yet it is uncommon for readers to be presented with such a comprehensive view of a publication’s development through time. This commemorative act, which was accompanied by a short history and a list of all the artists and authors who had contributed to the magazine, illustrated the extent of Ciel variable’s output and its formative role in the creation of photographic history – as a visual and physical object.

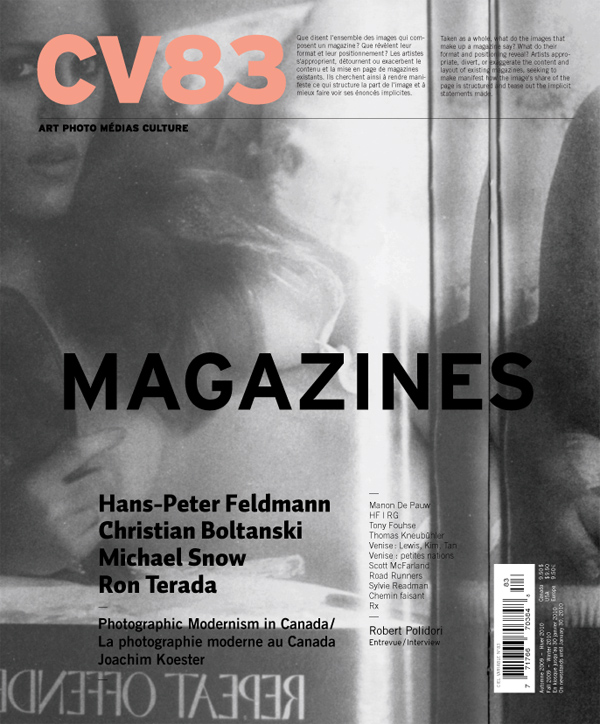

Illustration of the magazine’s objecthood reached new heights in issue 83 (Fall 2009–Winter 2010), which was titled “Medium: Magazines.” Devoted to the use of periodicals by artists, specifically Hans-Peter Feldmann, Christian Boltanski, Michael Snow, and Ron Terada, this issue considered the magazine as source material for artistic expression, but also reflected on the art of magazine production itself. It asked readers to become, in turn, conscious of the magazine medium and its impact on how photographic imagery is framed and therefore perceived. As Doyon wrote in the issue’s editorial essay, “For the image, the magazine goes beyond being a space for presentation to being one of enunciation.”8 For the history of photography in Quebec and Canada, Ciel variable has been just that: a space of enunciation.

I was asked to write this essay, and I was asked to write it for the Archives section of Ciel variable’s website. Is it paradoxical that the Web, considered the most ephemeral of contemporary media, is “hosting” an essay on the historical importance of a print magazine? It is, but this is exactly how things now stand. The ongoing threat of the dissolution of magazines has only been amplified by the Web. But at the same time, this very real danger has undoubtedly fuelled the recent scholarly revaluation of print culture. And so, the need to reiterate the purpose and history of the magazine is felt all the more strongly.

1 Advertisement for Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal (1st edition), Ciel Variable 9 (September 1989): 63 (our translation).2 Marcel Blouin, “Éditorial,” CVphoto 21 (Winter 1992): 5 (our translation). Blouin was involved with the magazine from 1985 to 1998. He was co-editor from 1992 to 1996.

3 Robert Legendre, “Éditorial,” CVphoto 29 (Winter 1994): 4 (our translation). Legendre was co-editor of the magazine from 1992 to 1996.

4 Marie-Josée Jean was active in the production of Ciel variable from 1995 to 1999.

5 Marie-Josée Jean, “La présence des photographies dans les collections des musées. Spécificité d’un médium… d’une culture/The Presence of Photography in Museum Collections: The Specificity of a Medium – and of a Culture,” special supplement, CVphoto 32 (Fall 1995): 27. The conference previewed by Jean was later panned by Sylvain Campeau in a review essay entitled “Le silence des agneaux.” See CVphoto 34 (Spring 1996): 5, 32.

6 Franck Michel, “Éditorial,” CVphoto 41 (Winter 1997–98): 4. Franck Michel was the magazine’s editor-in-chief from 1996 to 1999.

7 Jacques Doyon, “L’image sidérante/The Shattering Image,” Ciel variable 55 (Fall 2001): 3.

8 Jacques Doyon, “L’espace du magazine/The Space of the Magazine,” Ciel variable 83 (Fall 2009–Winter 2010): 3.

Zoë Tousignant is a historian of photography and independent curator living in Montreal. Her research interests centre around the dissemination of photographic culture in Canada, both historically and in the present. She has been a regular contributor to Ciel variable since 2008.

RELEVANT ARTICLES

CV83 – Matériau magazines

CV79 – Chantal Pontbriand, sur la situation des revues d’art contemporain

CV99 – Vincent Lafrance, ART SYSTÈME. Magazine d’art et d’idées