With the two-part exhibition Near You No Cold, you are presenting for the first time photographs that you took in India during three visits (one lasting four months). Images of different kinds are on view: interior scenes, street scenes, landscapes, still lifes. What image of India were you trying to capture?

For a Westerner travelling, it’s quite easy to take striking pictures of India. But what is being portrayed in these images is simply culture shock. One stays at a distance. Since I was in Mumbai to work, what was urgent for me was not so much to take pictures as to understand. First, I was struck by everything that was incomprehensible to me: human relations, class relations, and so on. Photography and videography helped me to apprehend this large Indian city and the people who live there.

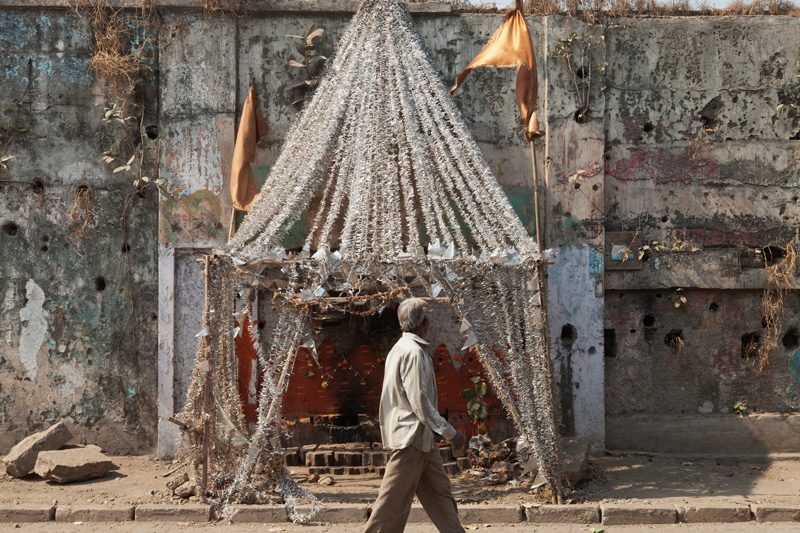

A clue to this search is the fact that you repeat a single motif several times, such as the small sanctuary composed of silvery garlands. The four-image sequence presents a sort of crossing of the space in which it is found. We sense, as we approach the work, that there are other images under each of the four images. We discover them by uncovering them, from very close by. Like you, we must immerse ourselves in the images to understand.

There are sanctuaries like this one all over Mumbai. This one was situated between the apartment (on Marine Drive, a rather upscale neighbourhood) and the studio (in Mazgaon, a very mixed industrial area). At first, I felt like making this trip of several kilometres every day was a test, because of the intense heat, the incessant noise, the density of the traffic, and, especially, because I felt like I had no reference points. The sanctuary became one. I glimpsed it from the taxi, then from the bus. Then, I made the trip on foot, and that’s when I photographed it at various times of day. Through it, I was able to master space, but also time. I saw the passage of light in the city and shadow invading the spaces enclosed by walls, like this one. Spectators who look attentively at the images of the sanctuary notice that a number of details change, such as the cobblestones on the street. This is because the images were taken over three years, and the city is constantly being remodelled by construction. Through the superimposed images of this fragile reference point, the sanctuary, I make transition, transformation, and movement visible.

This idea of movement and travel is central in the video. Although there are images of RA: all sorts, the street scenes taken on board vehicles are the guideline. The noise of horns, in fact, haunts the exhibition space.

You can’t ignore the incessant movement that creates the city’s rhythm. After a few days spent by the sea far from Mumbai, I felt anxious about returning to this torrid flow, which I saw as a kind of hell. But when I got back, I realized that I had to let myself be carried along by the movement. It’s like circulating in a large body. You feel incredibly small, replaceable, but also light, because you’re part of something huge and supportive. I never experienced this intense sensation anywhere else; it led to a sort of trance, of which I absolutely wanted to keep a trace.

It’s funny to think that the route to the studio became the subject of the work.

Not only the route to the studio, but the studio itself. As a photographer, I don’t work much in the studio. In Mumbai, it was in the calm of the apartment that I looked at my images, reflected on what I wanted to do. But because it was expected that I go to the studio daily, I made that site and its surroundings my subject. I started by inventorying what was there when I arrived: a bobbin of thread, a small white chair, a stool. I filmed a spider web – mobile, light, and solid. I photographed the window, the multi-coloured ground, and then the walled space of the yard. It made me think of a theatre. The sparsely scattered things there took on an existential status. I like vast, disordered scenes, such as the seaside in Bandra, sprinkled with rocks, and the sky covered with birds at Marine Drive. In these places, the body is still but the gaze moves all the time – here again, swept along in a sort of flow.

It was in the yard of the studio that you photographed the woman who was burning blue plastic tarps. What drew you to this scene?

A number of things, but mainly, I wanted to understand through her the amazing presence of Indians, their unique way of inhabiting their bodies, their gestures, which, one could say, are theatrical. I felt a certain absurdity in this handywoman’s activity in the chaotic, dusty yard, but at the same time I was attracted to the solemnity and great elegance that emerged from the scene. The jewellery, the colours, the drape of the dress, the tarp, and the fire . . . I had nothing to do at the studio but watch her. She saw me following her with my camera, and she continued to work quietly, smiling at me from time to time. When this surprising spectacle ended, she came to see me. I showed her the photographs.

There are a number of images of workers in the exhibition – a subject that you have not addressed very often, it seems to me. One might say that, through them, you are asking about the meaning of your own work. You stop to film their actions, and then you begin to walk again. Stillness and movement are constantly in dialogue.

Photographing workers is almost inevitable in Mumbai. The sidewalks are filled with people working, in plain view. Pedestrians walk in the street, among the cars. In the Mazgaon neighbourhood, which has no tourist attractions, I was quickly picked out: people greeted me, women touched me. This spontaneous contact surprised me. I felt welcome. It was the smell of the spices that drew me to the small shop that I filmed. It was also a smell, that of smoke – less pleasant – that led me to the scene of the woman with the jewellery. In India, all of the senses are summoned. The cramped space of the spice shop also formed a sort of theatre. It reminded me of Autoportrait au rideau, made in Montreal. The people who worked there welcomed me very warmly. After a few days, I asked if I could film them. I was attracted to the colours of the spices being ground by the mechanical pestles, but also by the gaze of the woman and the young man; their eyes were a movie in themselves. Indians’ faces are like that: they may open very wide, and then close off all of a sudden. A thousand things happen on them. In the novel Shantaram, the narrator says, “Indian actors are the greatest in the world . . . because Indian people know how to shout with their eyes.”1

No doubt, such gazes also gave you the impetus to photograph the group of women, also in Mazgaon.

What surprises me in this photograph – again, aside from its theatrical aspect – is how much the expressions on the faces differ. You might say we can see their thoughts. Each of the women is in her own world but allows a glimpse of an absolutely distinct presence.

Spectators who look attentively at the images of the sanctuary notice that a number of details change, such as the cobblestones on the street. This is because the images were taken over three years, and the city is constantly being remodelled by construction.

There is also a striking contrast between the images of these unknown people who look you straight in the eye and those of Ram, taken inside the apartment, whose gaze we don’t see.

When I arrived in Mumbai, I found out that Ram would be living with me for my entire stay, that he would prepare the food and take care of the house. Here again, I had much to learn. Living in a social relationship of this type made me uncomfortable. Communication between us was limited due to the language. But mutual respect was quickly established. As the days went by, we spent more time together. For me, the apartment became a happy place. I felt so good there! It took a very long time before I asked Ram if I could make an image of him. He immediately accepted and proposed that we do it the next day. That day, I photographed him at the window. The photograph sealed something between us. The oblique light was beautiful. It was reminiscent of Vermeer’s. I took very few pictures of him after that.

We can see how much you use art to deepen reality, to embrace it. In this conversation, you have several times made connections between what you experienced and different arts: photography, film, theatre, literature, and now painting.

It’s not just the ethereal light that I like in the photograph of Ram. There is the slight opening of the window through which you see more clearly the leaves on the tree outside. It gives an open yet closed image that makes me think of Ram. He allowed himself to be photographed while remaining deeply within himself.

The entire series of images made in the apartment dwells on this link between exterior and interior.

I was very frantic when I made them, just before I returned to Montreal. I wanted to remember happy moments. I didn’t want to come back. I don’t really claim to have understood everything, but I know that India deeply affected me and that it will stay with me always.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Charles Guilbert writes prose, poetry, a journal, and critiques. He draws, sings, and makes videos. His works have been presented in France, Luxembourg, Mexico, Japan, and other countries. His work has been included, among other events, at the Biennale de Montréal (1998) and the Manif d’art (2005). In the fall of 2014, he presented ink drawings and a short video at Galerie B-312 in Montreal.

Raymonde April has been known since the late 1970s for her photographic practice inspired by her private life – a practice skilfully maintained at the confluence of documentary, autobiography, and fiction. As a photographer, and also as a professor at Concordia University since 1985, she has had a significant influence on generations of young photographers in Quebec and Canada. She has had numerous exhibitions in Canada and abroad, including, in 2013, the FOCUS Festival in Mumbai. In 2004, she received the prestigious Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas, and her works are in numerous private and public collections.

www.raymondeapril.com

______

The artworks included in this portfolio have been shown in a combined exhibition at Centre Clark and at Donald Browne Gallery, in March and April 2015, in Montreal. Raymonde April is represented by the Donald Browne Gallery.

______