[Winter 2011]

A resurrection of hand-drawn film animation as a procedure to be presented in museum installations in this era of digital abstraction is a brilliant move. The simplicity of this strategy highlights the delusion resident in the efforts of so many contemporary artists to produce a critical art practice using technologically “advanced” techniques. In many cases, these attempts simply play a role in confirming the cultural status quo.

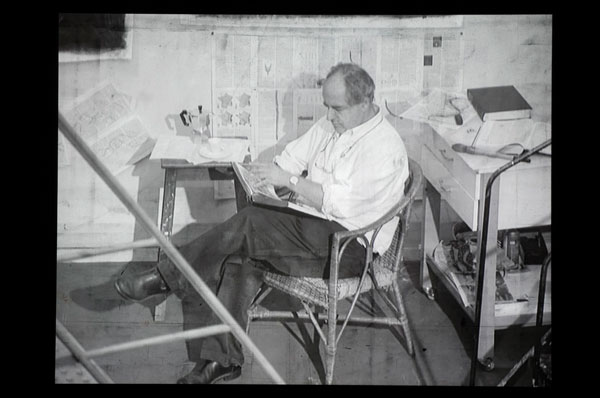

This summer, Le Jeu de Paume in Paris presented a retrospective of about forty of William Kentridge’s recent works, all of which offer for our consideration his continuing dedication to “the hand” and handwork as worthy of merit in contemporary art. The exhibition includes an earlier collection of films, Drawings for Projection, and a more recent work, Five Themes. Kentridge, born in South Africa in 1955, has received extensive international acclaim for his practice, which combines drawing, film, and theatre. He first gained recognition in 1997, when his work was included in Documenta X in Kassel, Germany, and the Johannesburg and Havana Biennials; ambitious solo exhibitions followed.

In the Drawings for Projection series, we encounter Kentridge’s characters Soho Eckstein, a rich businessman, and Soho’s angst-ridden alter ego, Felix Teitelbaum. During this one-hour cycle of animated films, we follow the pursuits and catastrophes of Soho and Felix, two fictional inhabitants of Johannesburg. The animation is remarkable for its wealth of primitive sensuousness and materiality, even though the medium is the technical one of photographic mediation and filmic projection. Drawn with soft charcoal (the ashes of burnt wood), these handmade animations let the dust fly as the technique records or traces itself out in the motions of composing image and story.

“Drawings for projection” is how Kent-ridge describes his hand-drawn animated films, and “palimpsest” is the term frequently used by commentators to describe the result of his unique combination of drawing, erasing, and single-frame filming. What seems unique in his technique is that both procedures, additive and subtractive, occur on the same sheet of paper. And what we see are, as films, visible scenes perpetually in progress, equally mechanical and artisanal, building and unbuilding as a process ongoing before our eyes. Marks and images are drawn and erased as the projection device moves the film always ahead, each frame displaced by the next.

What is most remarkable in this play between the handmade and the technical is that not only does the automated linear sequencing of film make the visible scene disappear, but the hand improvises the drawing’s disappearance by erasing fragments and layers of what has just been drawn in charcoal. A single drawing becomes the repository of its own disappearance while simultaneously becoming a cinematic appearance. What Kentridge is doing disrupts or cancels mechanical “clock” time and, in a way, the time of film projection itself, replacing it with an open-ended temporality; the result is the creation of a theatrical style of viewer involvement.

While temporal process may be the central attribute of the filmic medium, this is not entirely so, for drawing – a process of hand-worked inscription – gives a degree of fixity and permanence to artistic perception. And so, although initially we appear to be faced with a return of the anthropomorphic in Kentridge’s work, we are more accurately confronting a relationship between a handmade improvisation and a machine-made frame or technical image. This perception is encouraged by Kentridge’s choices not only of rudimentary technology and technique but also of dated imagery and styles in which technologies are less obscured by the familiarity resulting from prevailing usage. However, a perception of Kentridge as a typical proponent of expressionism, political doctrine, or other version of immediacy is countered by his appropriation of the technical apparatus and its regulation of the visible field. The fixed linear repetition of the filmic apparatus “exhibits” the organic expressiveness of the hand and thus critiques any notion of “the hand” or “the body” as a founding artistic concept, as pure spontaneous creativity. But, equally importantly, what is sometimes described as his “fusion” of media (film, drawing, theatre) is not that at all. He actually maintains the distinction between each medium so that they may interact, even to the point of friction or conflict, and retain a form of criticality that is directed by the questioning of the medium itself.

“The hand” is in quotation marks because I am referring not to Kentridge’s actual hands but to the hand as he pre-sents it in theatrical form. The hand is the star performer and, juxtaposed with film, compels an interpretation locating Kent-ridge in the questioning of humanism, although an argument to the contrary might be derived from the place of “transformation” in his oeuvre. Transformation is a decidedly technological “non-human” concern. It appears in examples such as that of a river disappearing as such in becoming a supplier of electrical power, a forest as such disappearing in becoming the daily journal, passengers being a “supply” for airplanes to transport. The dominant logic of film animation is that of transformation: in Kentridge’s drawings the narrative is that of objects being transformed into other objects, and he has referred to this practice as “the performance of transformations.”

The explicit political and social dimension in Kentridge’s imagery is constructed from a personal and, in the more recent works, autobiographical perspective. With an art career begun while South Africa was still in the grip of the apartheid regime, he has faced the constant question of how best to negotiate his positioning as a white, educated male unavoidably aligned with the powers of an oppressive state. The choice that he has made about how best to respond to his situation there has involved considerable subtlety; he has defined his work politically by way of process rather than by the route of explicitly political content. Attention to strategic manipulations of the modernist categories of medium, form, and content define for Kentridge a critical rigour that differentiates his trajectory from the arbitrariness favoured by so much contemporary art.

Stephen Horne is an artist and a writer whose essays have appeared in periodicals (Third Text, Parachute, Art Press, Flash Art, Canadian Art, C Magazine, Fuse) and anthologies in English, French, and German. He edited Fiction, or Other Accounts of Photography (Montreal: Dazibao, 2000) and published Abandon Building: Selected Writings on Art (Press Eleven, 2007). Horne was an associate professor at NSCAD from 1980 to 2005 and taught MFE seminars at Concordia University from 1992 to 2000. He currently lives in France and Montreal.

This text is reproduced with the author’s permission. © Stephen Horne