[Fall 2017]

By Joan Fontcuberta

What remains of photography in the era of post-truth and the selfie, of Facebook’s indiscreet rear windows and the Sirens of consumerism, emojis, and spam? Who will intone the elegy for the art of light? Just when we thought we had all the answers to the enigma of our memory fixed in silver salts, life – without so much as a by-your-leave – changed the questions. Perhaps because life is not a problem to be solved, as Søren Kierkegaard said, but a reality to be experienced. It is in these intellectual realms that the work of Michel Campeau, a photographer intent on squeezing the last drops from those silver salts rather than surrender to the overwhelming invasion of the pixels, defiantly runs its course.

Kierkegaardian existentialisms aside, photography was and is one of the pillars of the industrial revolution and the techno-scientific culture of the nineteenth century, and its invention is one of the cluster of innovations that fostered and boosted the dramatic expansion of modern transportation and communications systems: the railway, the steamship, and the telegraph. From an economic and political perspective, photography contributed, by means of its symbolic appropriation, to the control of the world and the visual formatting of its new spatiotemporal models. From a social and cultural perspective, the camera acted as an instrument of veridiction and of the archive, facilitating the mapping and encyclopedifying of knowledge. And from a spiritual or religious perspective, photography transcended finitude and death and aspired to magically supplant reality. The photographic image was destined to reveal the irreplaceable particularity of a life. Thus, in Giorgio Agamben’s view, the angel of the end of time – the angel of the Apocalypse of John – was one with the angel of photography.1

It is ridiculous to pretend that such values can remain intact in the twenty-first century. Today we are confronted by savage globalization and the virtual economy. Commodity capitalism has been swallowed up by a capitalism of images or, as Iván de la Nuez proposes, an iconocracy: the tyranny that the image exercises on us, which has demoted us from sovereigns to subjects. We inhabit a hypermodern society marked by consumption, quantification, excess, and urgency – a society in which the emphasis is no longer on the break with but on exacerbation of the values of modernity. We discover the world by way of digital screens that give access to a fluid, complex, and monitored reality. Internet, social networks, mobile phones, surveillance cameras, and myriad forms of graphic recording devices generate an oversaturation in which images are no longer submissive mediations between the world and us but have become active and furious.

The numbers for this massification have reached mind-boggling proportions. At the beginning of 2017, 800 million photos were being uploaded to Snapchat every day; to Facebook, 350 million; and to Instagram, 80 million. We can simply ignore the other platforms: if a single observer were to devote just one second of attention to each of the images uploaded every twenty-four hours on those three sites alone, it would take almost fifty years to see them all – if the observer never closed his or her eyes. Every minute that you invest in reading this text, a quarter of a million images are uploaded to Facebook. The paradox is that we no longer take pictures in order to look at them: we are drowning in images that almost no one sees. The outcome is that other values, such as connectivity and communication, now prevail over the photographic act. Post-photography thus ushers in a society that is losing its memory in order to gain more interaction. Science fiction augurs a world of screens, physical or immaterial, that we will access through a mental interface: screens that will provide us with multi-sensorial holographic representations from all angles and perspectives.

While this future of hypervisibility is being consolidated, post-photography predisposes us to a world of ubiquitous images with neither body nor support. It is blindingly obvious that photography is no longer just a “writing of light” practised by privileged scribes but has become a universal language that we all use naturally in the many and various facets of the everyday. It is this that I propose to call the advent of Homo photographicus. But that universality, and the excess that goes with it, imposes a toll on what has until now been the ideological scaffolding of photography: we are entering new regimes of truth and memory. The uncertainty about the documentary value of the post-photographic image has received a great deal of attention: the camera has shamelessly renounced its power of conviction, its capacity to persuade. Memory, too, is affected. If photochemical photography was associated with the prodigious memory of an elephant, the post-photograph has the precarious memory of a fish, which is said to last only a few seconds.2 The paradigm of this “fish memory” is Snapchat. Enormously popular among young people, this application for sending and receiving photos and videos automatically deletes messages after ten seconds. This is the ecstasy of the present at the expense of the past: a “now” in suspension, eternalized as a limbo between the horizon of experiences and that of expectations. Post-photography replaces memory of the past with nostalgia for the present.

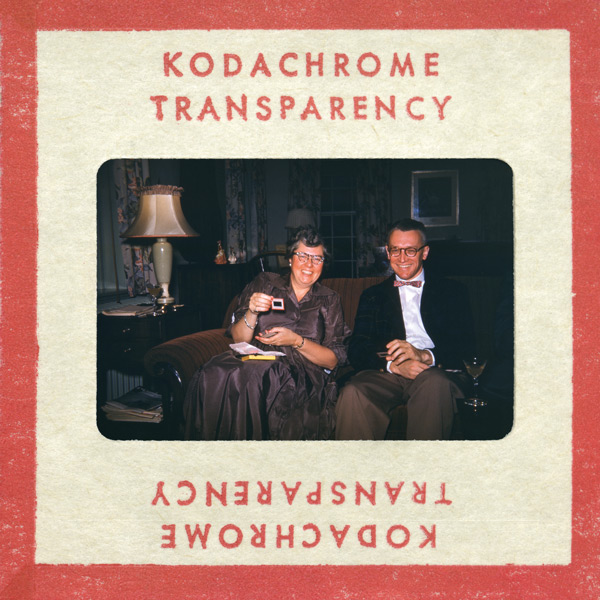

We respond to these changes with both hope and uneasiness, and in artists (among others) this ambivalence generates attitudes of resistance and critical witness-bearing. For example, the return to nineteenth-century artisanal processes and the recovery of discontinued materials such as Polaroid film not only reflect a retro sensitivity but can also be read in terms of militancy and activism. The fact that many photographers are going back to the analogue cartridge can be explained not only by nostalgia but also by a rejection of all that digital culture represents. For similar reasons, there have always been photographers who have preserved the practice of the daguerreotype and other archaic systems. This can be understood as a preference for the process itself, over and above its relative effectiveness for the purpose of communication. We travel by car, but a few of us still ride horses, due to either snobbery or ecological awareness. Neither film cartridges nor horseback riding will disappear completely, but they have become exceptional and unsustainable.

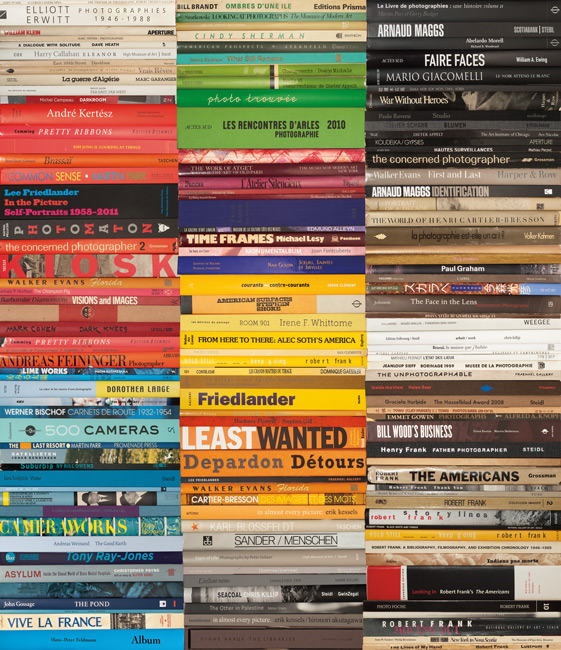

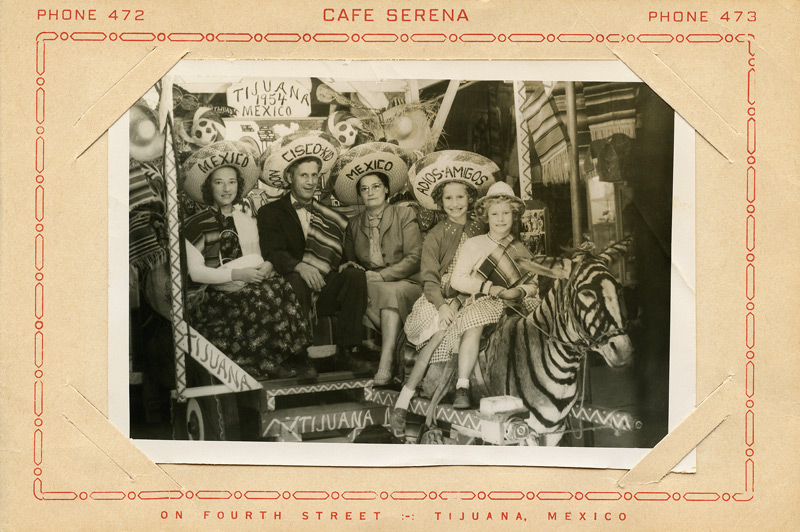

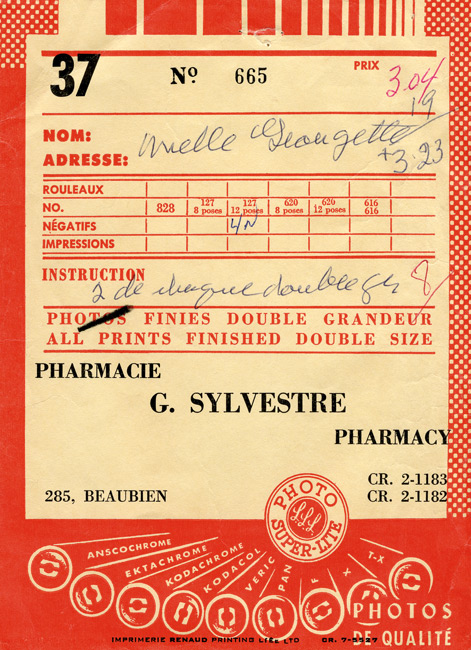

Other forms of resistance champion what has been sidelined and marginalized, what has failed to obtain the blessing of the canonizing institutions. It is in this light that we can interpret the increasing reaffirmation of the value of the vernacular: family albums, amateur photography, popular advertising, commercial photography, pornography, forensic documentation, and other areas of production classed as forms of low culture. We justify the phenomenon on the grounds that it privileges a sociological approach to the mounds of photographic waste, which will compensate us by enriching the aesthetic heritage with the unexpected, the accidental, the overlooked, and the hope of finding neglected gems in the most lumpen repositories, to glimpse flashes of gold in the mass of anodyne images. Outside of the academic sphere and its evident emphasis on a sociological and anthropological engagement with vernacular photography, the pioneers in recovering this kind of material for art were Hans-Peter Feldmann and Sándor Kardos. The latter founded the Horus Archive and declared that the act of collecting was an independent art form, with value equal to that of the actual taking of photographs: to select an image from many available images is equivalent to selecting a shot from many possible shots; the creative act consists not so much in producing as in choosing. Today, the legacy of Feldmann and Kardos is kept alive by photographers such as Martin Parr, Erik Kessels, Joachim Schmid, and Michel Campeau, but almost fifty years after the pioneers, this second generation has gone from making dazzling discoveries and celebrating happy accidents to recording the swan song of a once exuberant photography now in its death throes.

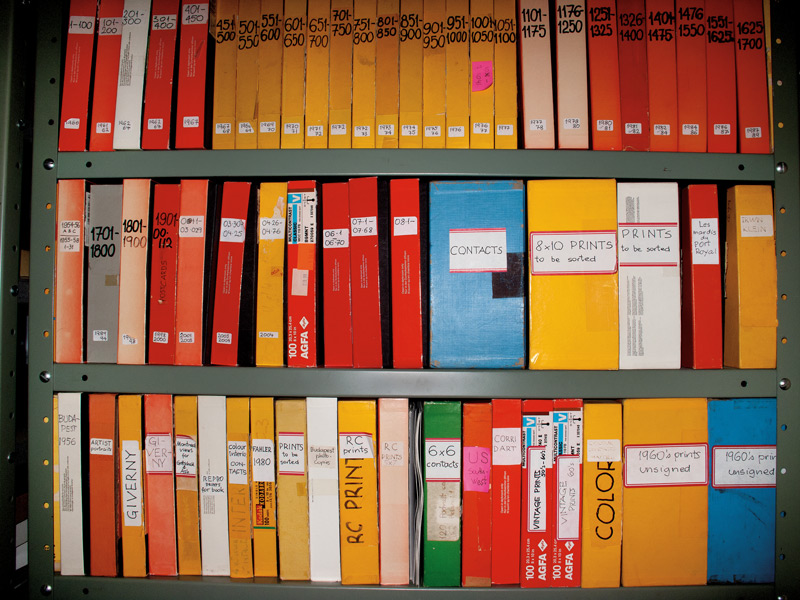

To combine this kind of vernacular material with images from the darkrooms of yesteryear, as Campeau does, is to enact a commitment to narrating the end of a (hi)story. The old photo labs were the ritual caverns in which the miracle of light was celebrated. If the camera was the place of insemination, where the image was conceived, the darkroom was the birth channel. Many of today’s digital-era photographers know nothing of the darkroom – its mystery and its intoxicating effluvia, the experience of safe-lit darkness, the exultant poetics of the wait, the euphoria and the frustration, the pain of a forceps delivery, and the joy of the first cry – these sensations now lie in the sediment of an enchanting past; the darkroom has become a sanctuary-relic. Campeau retains for posterity those odd corners, impregnated with magic and memories that want to tell us something, or that have indeed said something we should not have forgotten. It is the imminence of a revelation that does not come to pass . . . or better yet, of a testament.

Given that writers write about the art of writing, there is nothing untoward about photographers photographing the act of taking photographs, or what is left of it, or what is attached to it. This is what Campeau does, and he does so as an exercise in conceptual art in which the gaze precedes the concept, in which the intensity of the words – which, here, are images – prevails over the depth of the story. There are amnesic modernities that are raised on the abolition of the past. Campeau’s is a modernity constructed with the materials of memory, with the scraps and ruins of a yesterday that seems remote but was only a very short time ago – a yesterday that was swept away in no time by the alluvial accumulations of vertiginous post-photographic images.

It is said that at the moment of our death, with our last gasp, the most important events of our life pass through our minds. The sequence of materials that Campeau offers us here can be understood as that succession of visions, a handful of moments and places that filled photography with happiness and to which we cling as we take our leave of it, as a way of ensuring that we at least retain the story.

Because it’s a matter of conserving the story above all else. In his book The Fire and the Tale (Il fuoco e il racconto, 2014), Agamben retells the story of Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1790), founder of Hasidism, known as the holy Baal Shem. When he was faced with a difficult task, he would go to a special place in the forest, light a fire, and meditate in prayer, and the task would resolve itself. The years went past, and his successors forgot how to light the fire, but they went to the forest and prayed, and everything continued to go as they wished. The same thing occurred in the next generation, and they went to the forest and said, “We can no longer light a fire, nor do we know how to say the prayers, but we know the place in the forest, and that can be sufficient.” And it was. In time another generation had passed, and another successor had to perform the same task: “We cannot light the fire, we cannot speak the prayers, and we do not know the place in the forest, but we can tell the story of all this.” And, once again, it was sufficient. With photography, we too have lost the fire, the prayers, and the place: we no longer have the truth, or the memory, or the encapsulation of transience, or the revelation of the identity, but Campeau preserves the history – its crumbs, at least – and we can hope that once again this will suffice.

In this book, Campeau succeeds in getting us to look at every image, even the most commonplace, with the suspicion that it may be a revelation or a threat, an inexplicable piece of future archaeology. And we end with the print of a donkey done up as a zebra. This is a beautiful, illuminating metaphor of post-photography: an image that is clumsily disguised as a photograph, passing itself off as photography, and that we can even laugh along with, but that cannot prevent us from recognizing its true nature and its false promises of salvation. Hence the programmatic nature of this project. To photograph is to find the right images to convey something, but it also means letting the images find us, even if they then slip away from us when we think we have mastered them, only to reappear, epiphanically shaking all our thoughts. And from the heart of an infinite melancholy this is precisely what happens here.

Translated from Spanish by Graham Thomson

2 So much for popular belief: in 2014, researchers at MacEwan University in Edmonton found that the episodic memory of the African cichlid – a fish commonly found in domestic aquariums – could be as long as twelve days.

Michel Campeau’s work extends over the past four decades of contemporary photography. Expressing a concern for interiorization at odds with the medium and breaking with the formal conventions of the documentary, he explores photography’s subjective, narrative, and ontological dimensions. His work has been shown at and acquired by numerous Canadian and international institutions, been published, and received numerous awards. Campeau lives and works in Montreal, where he is represented by Galerie Simon Blais. He is also represented by Eric Dupont Gallery, in Paris.

Joan Fontcuberta is a renowned conceptual photographer and a writer, editor, curator, and teacher; he has played a significant role in achieving international recognition for the history of Spanish photography. He was one of the founders of Photovision, launched in 1980, which became a major magazine on European photography. His work has been exhibited and collected internationally by prestigious institutions, and he has received many distinctions, including, in 2013, the Hasselblad Photography Award.

![Michel Campeau, Sans titre [Montréal, Québec, Canada], de la série / from the series La chambre noire, 2005-2010, impression numérique / inkjet print, 69 × 91 cm](https://cielvariable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/107-12-michel-campeau-1.jpg)

![Michel Campeau, Sans titre [Montréal, Québec, Canada], de la série / from the series La chambre noire, 2005-2010, impression numérique / inkjet print, 69 × 91 cm](https://cielvariable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/107-13-michel-campeau-1.jpg)