[Fall 2017]

By Sylvain Campeau

It has often seemed to me that Joan Fontcuberta’s particular aesthetic involves two complementary aspects. One aspect might bring together works such as Fauna Secreta, Sputnik, The Artist and the Photograph, and the Miracles & Co. project. In all of these series, the photographic image is presented as an exuberant testimonial, a trace of an invented real, a convincing artefact of a reality constructed on the basis of a medium perceived as purely documentary. In the other aspect, the truth of the photograph is the result of its flat reality – the apparently immediate contact between photosensitive paper and a material that permeates it. I am thinking here of series such as Constellations, which seem to be shots of starry skies but are in fact photograms of insects that are crushed on the windshield of Fontcuberta’s car as he drives. Fontcuberta plays with similar traces in other series: in Hemogramas, he makes images from dried blood; in Frottogramas, Palimsestos, and Terrains vagues, the trace of a photogram is never far from the direct intervention on the paper; it almost looks as if the images he creates are thrown directly onto the sensitive material of the print. In the transition from one aspect to the other, the photograph is held up to a measure of authenticity. But can this authenticity be understood as having a relationship with the real or must it be reduced to its visual reality, its status as trace by contact, its infusion with chemical substances? The image, in its analogue dimension, is co-presence – evidence of what has been placed in the presence of the camera. In the case of the first aspect described above, the reality of events, narrativized accounts of facts presented as actuality, is suggested. In the case of the second aspect, it is the truth of the contact that is at issue. It is as if Fontcuberta is evoking the very status of the photograph and its documentary capacity: first, as fact presented as reality; second, as reduced to materials in contact, in which would reside the true reality of the image, of images.

Of course, since then Fontcuberta has produced the Orogénesis and Googlegrams series, in which the photographic image is measured against its dispersion, its incredible amplification, and the way in which it is changed by its digital version and its absorption by the web, making it both protean and ubiquitous. We are now in the realm of the digital, less concerned with the visual reality of the image, which no longer seems to conform to this reality, than with its fluidity, its incapacity – by nature, one might say – to attach itself anywhere except for a brief period.

In short, it is as if Fontcuberta’s production has evolved alongside new developments in how photography can be thought of and measured, through the changes it has undergone in terms of materials and significance. Thus, we can understand Fontcuberta’s practice as quite exemplary of what happens to photography as it is absorbed by digitization and then subjected to the imperatives of its dissemination through all imaginable networks established after this fundamental alteration. It is an evolution magnificently challenged by Fontcuberta’s inquisitive and innovative (and intellectually rebellious) mind.

This is how we should address how the series in the exhibition Trauma at Galerie Occurrence and at Centre VU are almost both combined and compared.1 There are three of them: Blow Up Blow Up, Gastrópoda, and Trauma, the last of which lends its name to the show’s title.

The first gallery contains wide sections of Blow Up Blow Up. This ensemble of three attached images, in two different combinations, obviously refers to Michelangelo Antonioni’s celebrated 1966 movie Blow-Up, so often cited in scholarly analyses of the status of the image. Thomas – whose character, it is said, was inspired by David Bailey – is an eccentric fashion photographer who looks and behaves like a typical 1960s bohemian. His relationship with time seems to be based on photographic method – sometimes frenetically taking pictures, sometimes slow and unaware of what’s going on in front of him, depending on whether or not he is on the hunt for images. On the hunt or at rest, he may take and immediately abandon what he captures. Chance leads him to a park, where he takes a picture of a couple of lovers who are behaving strangely. When he enlarges the photographs (as it was done at the time), he follows the upset woman’s line of sight to make out the images of a corpse and a sniper’s gun, almost unintelligible in the oversized silver grains. He returns to the park to confirm what he has seen, but everything is gone. There is no evidence of the reality – a reality that he hadn’t actually captured but was captured inadvertently by what the photograph could see.

It is these oversized enlarged prints that Fontcuberta hung on wires, as one would do with an image to dry it after developing. Except that these reprised images have been made with a digital camera, superimposing the rendering of pixels over the artisanal grain of the original analogue version! Beyond this, we still stumble over the ambiguous status of the image as proof of the real – a notion, of course, that has long been debated. But Fontcuberta sees in this excerpt the manifestation of a long-term critical project, the interpretive heritage of which lives into the present. He even adds, in the mischievous insight for which he is known, a final step. What is seen here, in both the photographic images and the video excerpt in which Thomas examines the image and enlarges it over and over, is not so much an actual murder but the figurative murder of representation itself.

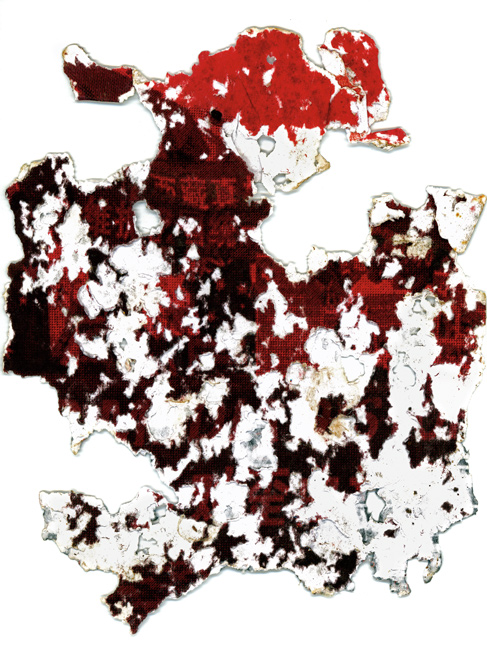

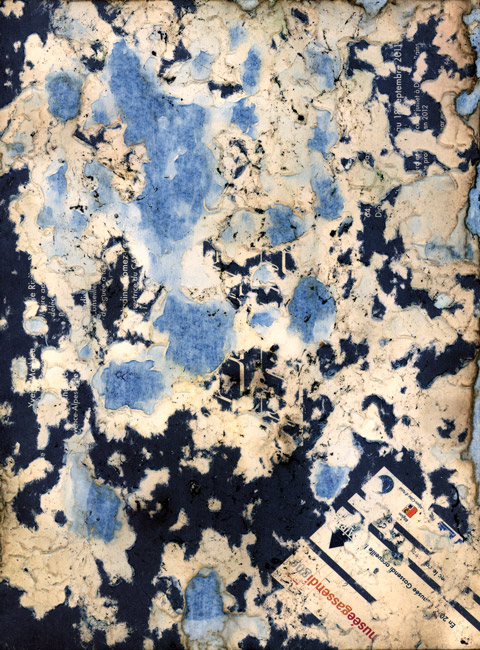

Gastrópoda is based on the voracious appetite of snails and their propensity to munch on photographs and invitations. Delegated as authors by definition, these little molluscs lacerate the paper to the point that they reveal the entrails of the material, repository of chemical or digital images. They offer a parallel to our role as image consumers: we constantly take and retake various images, stealing them, ingesting them, and recycling them like the snails do, using our postmodern and post-photographic tools such as social networks and other media. It is the vestiges of this never-totally-completed consumption that Fontcuberta’s images show.

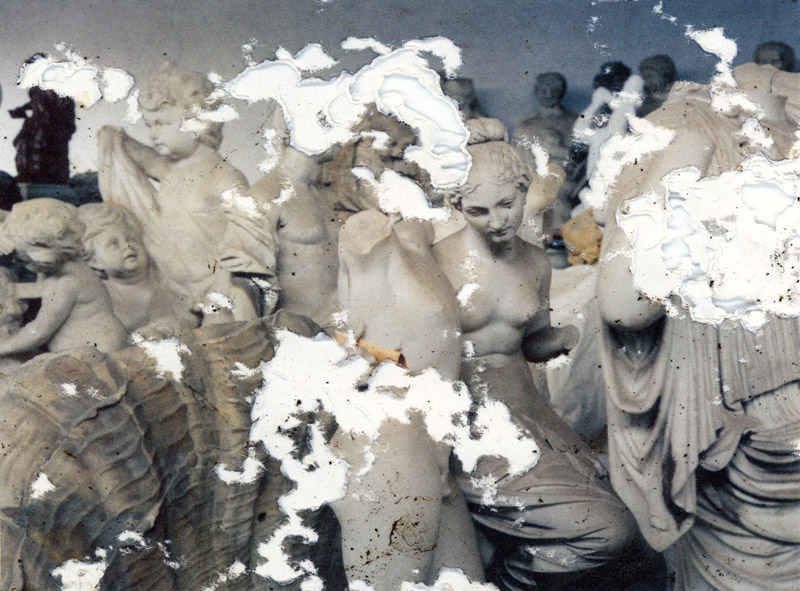

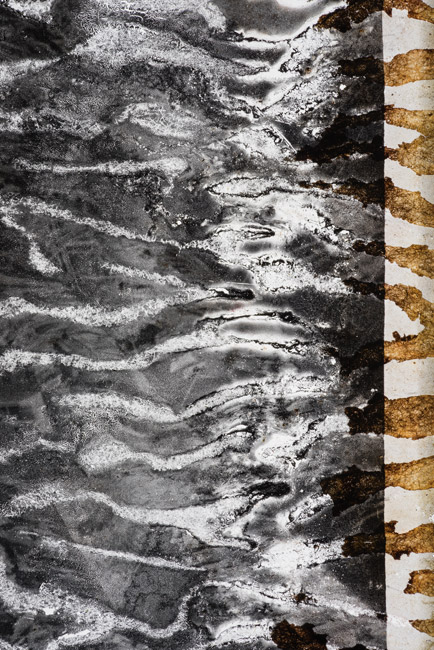

Trauma closes the loop, returning to the materiality of the image as the physical and chemical trace that has for the most part been abandoned in favour of digital. Fontcuberta has appropriated images from archives. These images, damaged by time, stained, accumulating the traces of chemistry gone rogue, show the raw material of photography, the image resulting from a densification of silver salts produced by the effect of light. In that sense, this last opus is related to Constellations – or to other, older series, such as Ría de Bilbao (1993–94), in which, on the background of images of an industrial area of Bilbao soon to be destroyed to make room for the Guggenheim Museum, he superimposes photograms of objects found on this cleared site.

From these images with a high potential for nostalgia to those in Trauma is just one step. Except that in the more recent series, this introspection on the material of photography appears against the background of upheavals revealed by postphotography – of which Fontcuberta is one of the developers (in the photographic sense) – like a sort of autopsy performed on the still-warm body of the mother lode.

Translated by Käthe Roth

In his work, Joan Fontcuberta explores the effects of the real and the capacity for truth generated by the technological image, in order to denounce the authoritarian discourses regarding information and knowledge. His other subjects include nature and the functions of the image in digital culture. His work has been shown in and is collected by major international institutions and has won numerous awards. Aside from his work as a visual artist, Fontcuberta has a multifaceted career as teacher, writer, and exhibition curator. Pandora’s Camera, his most recent book on photography, has just been published in French, at Éditions textuel, under the title Le boîtier de Pandore. La photographie après la photographie.

Sylvain Campeau contributes to numerous Canadian and European magazines. He is the author of Chambre obscure: photographie et installation, Chantiers de l’image, and Imago Lexis, as well as five books of poetry. He has also curated thirty exhibitions.