[Fall 2018]

By James D. Campbell

In a remarkable group exhibition recently on view at Optica,1 Raymonde April, one of Canada’s finest living photographers, marshalled the talents of an intrepid group of itinerant fellow travellers – and to radiant effect. April formed Outre-vie/Afterlife in 2013. The group comprises thirteen accomplished photographers2 all of whom work from and contribute to the notion of an “afterlife” that is native to the idiom of photographic images.

Taking its cue from a work by the late Quebec poet Marie Uguay, the cabal is devoted to an open-ended dialogical investigation (there is nothing doctrinaire or solipsistic at work here) of what “afterlife” – understood as thematic chrysalis and unique point of fulcrum, using narrative means to achieve mnemonic ends and vice versa – might mean. Members of the group have in tandem exhibited large-scale photographs, video projections, object installations, experimental writing, and sound installations in Quebec and abroad in institutional exhibitions and performative and archival contexts. The work on display at Optica is mostly photographic. April and her coalescent hive mind are all empowered by what Uguay wrote:

Afterlife is when one is not yet in life, when one watches it, when one seeks to enter it. . . . Afterlife is like overseas or beyond the grave. One must pass beyond the rigidity of the obvious, of prejudice, of fears, of habits, pass beyond the obtuse real and enter into a reality at once more painful and more pleasant, into the unknown, the secret, the contradictory, open one’s senses and know. Pass beyond the opacity of silence and invent our existences, our loves, where there is no longer destiny of any kind.3

April herself says, “I imagined forming a group that could collectively map the existence of photographic images – their past and their future. I wanted to create a community that could consider the way images have their own space and their own lives, and how they respond to you when you look at them.”4 That she has brought such a community into existence is clear.

The catalyst for realizing April’s desire was a residency in Mumbai:

When I went to India for the first time in 2012, for a residency in Mumbai, this project was still living in me but was not yet born, in a sense. I needed to make images just to understand what was going on in Mumbai. When I came back to Montreal, Mumbai was like a surreal fantasy that inhabited me, because no one else around me had been there. I invited more people into the story that was emerging and they had their own affinities. Our practices as image makers began to reflect and expand the concept of afterlife so that it gained new values and meanings. Some members of the group explored geographies that resonated with spectral traces of disappearance. At the same time, others found, in the sculptural forms of objects, ways to observe or distinguish layers of history and memory embedded in the material world. Eventually, more and more members of the group went to India. It’s a biographical thing. It just happened this way.5

April started the “research group” at Concordia University. She had originally planned for it to involve graduate students, but she eventually invited both students and fellow teachers to join. Most of the students have now graduated, but the collaboration, which has metamorphosed into what is almost an organic process or an “afterlife,” lives on.

Normally, research groups have a formal structure and a physical space within the university, but Afterlife would be different from the outset. Members of the group started meeting outside of the university. They shared meals, travelled together, and did some fieldwork. The Post-Image Cluster at Concordia remains something of a home base for them, but they work mostly on production issues there, and most of the production is done by individual members and not by the collective as such.

Jessica Auer, the noted photographer and teacher, says, “Our ‘research’ usually takes the form of sharing work, storytelling, and photographing together. We’ve done some overnight trips to Kamouraska that have been very productive.”6 Kamouraska is April’s home turf. She cultivated what was already a trait shared by most photographers in the group: a decidedly nomadic and somewhat maverick propensity.

The eponymous Optica exhibition includes some arresting images and gives us an opportunity to understand something of the collective spirit and imperatives of the group. April’s own images in the exhibition offer a sort of diaristic sortie through her august body of work, and it’s heady stuff. Classic early images that many viewers are already familiar with, such as Autoportrait, Québec, juin 1978 (2016, inkjet print on Tyvek, 36 × 51 cm), are interleaved with more recent photographs taken in Mumbai. They all share the photographer’s trademark ascetic and laconic aesthetic.

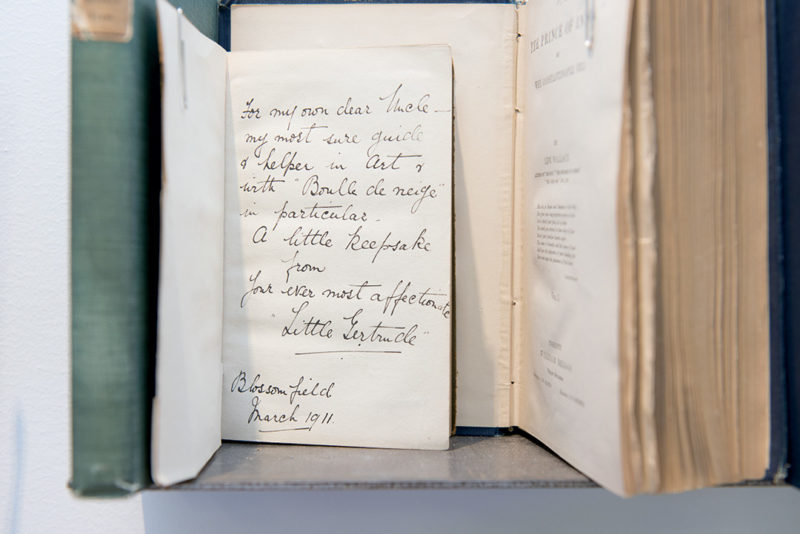

Velibor Božović’s work also runs the gamut from accomplished earlier black-and-white images from his voluminous archive to work done after his immersion in the group. His great love of books is felt in one of the few object installations in the show, composed of an audio piece and a hundred sundry books and shelving, Encore/Odyssey (2011–present). The selected volumes, each one marked in a different year of the twentieth century, demonstrate his quirky reading propensities. It is a wonderful valorization of the library. The audio piece is a compilation of paragraphs from each of the books, enunciated in the inimitable voice of the artist jake moore. Božović says, “One of the many qualities of being part of this collective is that we all somehow preserved our own distinctive practices while being able to share work and exchange opinions and ideas. Working ‘alone together’ was something of an inside joke within the group but it is actually quite accurate.”7

The gifted young nomadic South Korean-born photographer Jinyoung Kim seconds Božović’s sentiments. Her powerful images of her parents and their home in Seoul, South Korea (also showing at Galerie Patrick Mikhail in Montreal), are accompanied by several powerful images taken in Mumbai. Celia Perrin Sidarous is represented by several images that serve as a compressed vision of her poetic, idiosyncratic practice. Her interest in historical artefacts, so evident in her recent show at Parisian Laundry in Montreal, is seen again here in works such as Fragments, side view, Acropolis Museum (2015, inkjet print on matte paper, 46 × 34 cm).

Veteran photo-based artist Andrea Szilasi’s large collages in grey and black tones are particularly striking in gravity and aura. These are part of her Plotter Prints series; they were printed during the course of her MFA studies at Concordia University and exhibited in their entirety at Joyce Yahouda Gallery in Montreal. Chih-Chien Wang’s inordinately eloquent, spare aesthetic is another high point of the show, particularly in images such as Light and Lamp (2018, inkjet print, 76 × 51 cm).

Jessica Auer’s nomadic images are also highly resonant. Her work entitled Neon, January 12th, 2016 (2016, solvent print on clear film, in lightbox, 31 × 46 cm) is one of her finest. Auer and April, both teachers known for excellence and dynamism in the academy, were certainly creative spurs for the collective’s work. In her continuing projects, in Iceland and elsewhere, Auer investigates how tourism is changing previously unspoilt environments beyond any hope of reparation. Her imagery, with its grandeur and scope, is always arresting.

Auer says, “I would say that our main purpose is to consider the ‘other lives of images.’ We think about this within our own practices and as a group, sharing our own individual works within a collective. But if you asked another member what we are about they are likely to say something different and that would be totally all right. We like how our stories often get mixed up or crossed.”8

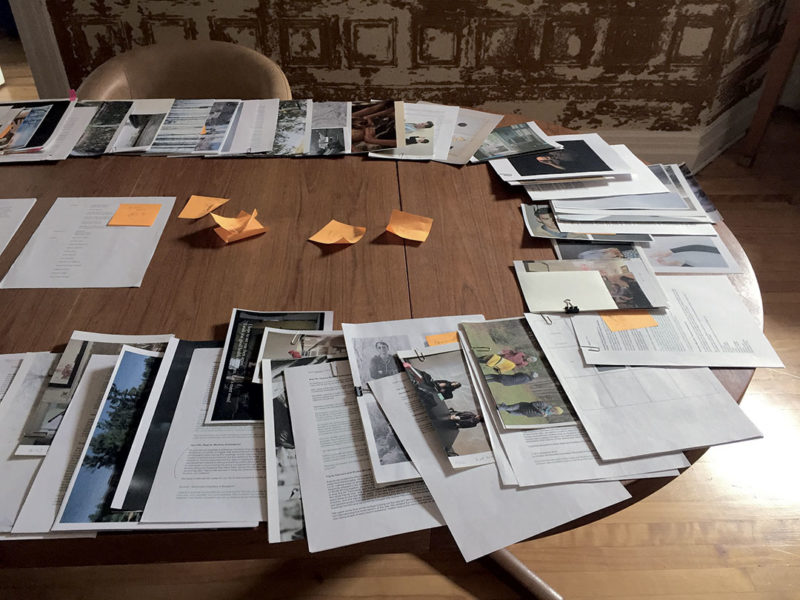

The exhibition also includes nomadic images taken both in Quebec and in far-flung locales such as Tibet and Athens by other members of the group: Jacques Bellavance, Gwynne Fulton, Katie Jung, Lise Latreille, Marie-Christine Simard and Bogdan Stoica. April’s first move was to enjoin her fellow travellers to engage in a sort of communal imagistic storytelling, which is deeply rooted in memory and nomadism and has ritualistic overtones. This preliminary instruction (or, better, invitation) meant opening up the archives of the participating photographers, to see what might fall out. That some real gems did is clear from what fills the walls now at Optica.

The archival injunctive was and remains crucial. As April says,

It was logical . . . that we would create a living archive that continues to multiply and proliferate. Through this collaborative process of montage and juxtaposition, overlooked fragments of memory were recorded and gathered in a shared space, giving rise to unexpected new trajectories. This mode of collective work has allowed us to examine the fluid boundaries of self and other, memory and forgetting, reality and fiction, and continuity and fragmentation in generative ways.9

The archive is a powerful inventory the contents of which move restlessly forward and backward in time, releasing hidden stores of meaning, opening up new possibilities, contributing to chiasmic dialogue. This dialogue is not limited to members of the group in question but extends outward to viewers, enjoining that they also bring their interpretive offerings to the table.

Philosopher Jacques Derrida once described “archive fever” as “to burn with passion. It is to never rest . . . from searching for the archive right where it slips away. . . . It is to have a compulsion, repetitive, and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.”10 Clearly, April shares this understanding of the archive, and has communicated it to the collective that she directs.

In this sense, Afterlife cultivates modes of community through the creative act. This idea of “communitas” (communitas being a Latin noun that refers to an unstructured community in which people enjoy equality, or to the very spirit of community itself; in anthropology, it means that sense of sharing and intimacy that develops among persons who experience liminality as a group) is here transformed into a photographic ideal. Noted anthropologist Victor Turner emphasized the importance of storytelling and focused his exploration of liminality primarily on the rites of passage that specifically concern initiation. In his view, such processes embody the ecstatic transitionality, or the essential becomingness, of the liminal state.11 Similarly, April embraces the importance of a provisional and mutable aesthetic and encourages her nomadic cohorts to tell stories from past, present, and future.

This is certainly true of the images of the Afterlife collective, which is understood as a seedbed of creative storytelling. What is perhaps even more remarkable is the way that the images in question draw out a radius that encompasses the viewer as well, and the circle is closed when we experience the same liminality shared among members of the group, by looking hard at their photographs and coming to understand something of the how and the why of their going down to the deep well.

2 Raymonde April, Jessica Auer, Jacques Bellavance, Velibor Božović, Gwynne Fulton, Katie Jung, Jinyoung Kim, Lise Latreille, Celia Perrin Sidarous, Marie-Christine Simard, Bogdan Stoica, Andrea Szilasi, and Chih-Chien Wang.

3 Marie Uguay, L’outre-vie (Montreal: Éditions du Noroît, 1979), 9.

4 Raymonde April, interview with Gwynne Fulton, in Outre-vie/Afterlife (Quebec City: VU, 2018), 7.

5 Ibid.

6 Author’s conversation with Jessica Auer.

7 Author’s conversation with Velibor Božović.

8 Author’s conversation with Jessica Auer.

9 April, Outre-vie/Afterlife, 7.

10 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 91.

11 Victor Turner, “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage,” in The Forest of Symbols (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967).

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator who writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 110 – MIGRATION ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Afterlife – James D. Campbell, In Pursuit of the Afterlife ]