[Fall 2018]

By Pierre Dessureault

Photography. The exhibition Michel Campeau – Life before Digital,1 a retrospective of Michel Campeau’s approach in the early 1970s, offers a wellrounded view of his ideas on photography, on the figure of the photographer, and on that of the collector who finally took over from the producer of images. In The Donkey that Became a Zebra, as well as in his series La collection Bruce Anderson and La chambre noire, which open the exhibition, Campeau compiles an almost archaeological inventory of the medium of photography as physical and chemical image production process. Ranging from objective views of historical photographer’s tools, reproduced to highlight the beauty of their mechanical precision, with “a host of images gleaned here and there from the historicity of the ‘discourses’ on photography and its industrialization,”2 to the personal register, with montages that reconstruct his selftaught photographer’s library and a portfolio of photographs in the name of Mlle Georgette (Campeau’s mother), these corpuses of disparate images read as vestiges of an obsolete art issuing from the industrial revolution. As an extension of this collection of artefacts, views of darkrooms offer a reminder of what one might call the photographic kitchen. These creative workspaces were cobbled together by the photographers and organized according to their creative needs. Campeau brings them to life through a play of light and chemicals that reveals their precariousness. The crude light of a flash hollows out their details, magnifies their textures, saturates their colours, and exaggerates their pictorial qualities, transforming these darkened rooms, with drawn from the world, into gaudy tableaux featuring the instruments through which images transitioned from virtuality to reality.

A series of pictures of photographers at work in the darkroom celebrates different stages of this process. Concentration. Attention to detail. Precision. In the end, an image revealed on a sheet of paper. This motif of the materiality of images is recurrent in Campeau’s work; we might think of the grey frames around the images of Week-end au “Paradis terrestre”!, the black backgrounds against which stand out family snapshots and photographs borrowed from revered masters in Tremblements du cœur, and the successive reframings, solarizations, and negative and positive effects that shape the particular texture of Éclipses et labyrinthes. All of these traces belong to the process that melts into and becomes one with the image. In recent works, the red frame typical of Kodak slides plays a similar role, as a reminder that before being images, silver halide photographs are material and method.

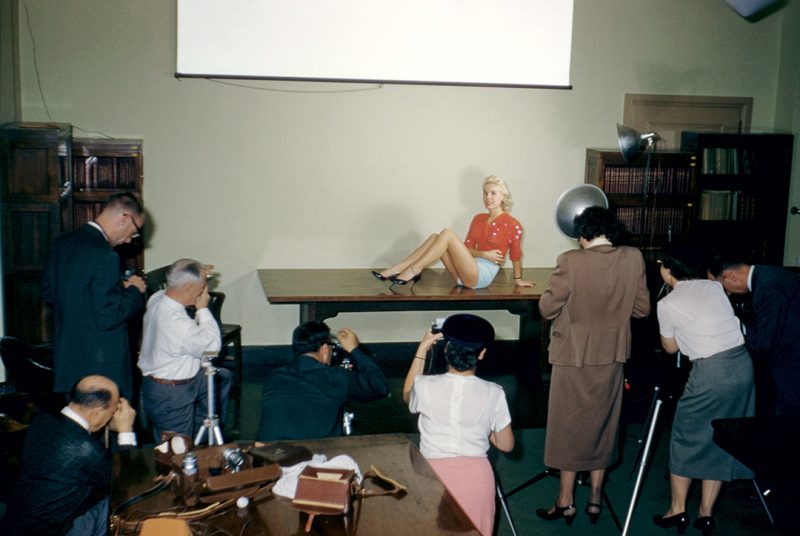

The Photographer. The marketing of the first Kodak camera in 1888 and the standardization of production protocols that it brought in its wake led to mass access to photographic practice. This gave rise to the figure of the amateur photographer who took pictures for his or her own pleasure without regard for received ideas on aesthetics and, most of the time, solely to immortalize special moments in daily life in the vernacular form par excellence, the snapshot. Campeau was an early adopter of the codes of this popular use of the medium. His images of residents of his neighbourhood in 1971 and those in Disraeli, une expérience humaine en photographie fall naturally within such a direct approach to people and things. The photographer’s familiarity and ties with his subjects is manifest: they look him right in the eye and pose in their usual living environment, usually facing the camera head-on. Here, Campeau has ample room to present people straightforwardly, without aesthetic detours, and, above all, to make known his affinity for the working classes. His snapshots show shared moments, forming a portrait of the community modelled on the family album. Week-end au “Paradis terrestre”! claims a piece of the photographer; he stamps his character on the image by assuming his dual role of observer and commentator of the rituals of social life, in which he participates through the photographic act. In this sense, his amused, sometimes ironic gaze at these amateurs at work constitutes a commentary on the social uses of photography. The recent group of pictures taking up the same motif is situated in a different register. Abandoning critical distance here, Campeau appropriates these images to highlight his admiration for and take as his own the body language of these amateurs, absorbed in taking their own pictures.

The figure of the photographer as protagonist of the photographic act takes an autobiographical turn in Les tremblements du cœur, one of the emblematic images from which is prominently displayed in the current exhibition. The composite formed of a self-portrait at the light table and a snapshot taken from Campeau’s family album against which are juxtaposed the words “L’enfance me court après” (Childhood is running after me) fading into the black of the photographic matter inaugurates a long introspective journey of singularization. Two spaces of memory are superimposed: that of childhood, formed of snapshots recording the past, and that of the photographer who grabs moments from the present and tries to play on resonances among the images to bring to light the texture of life of a creator who is also a son, spouse, and father. In this approach, the photographer, as both author and assembler of images, and his subject are merged in an open narrative. Éclipses et labyrinthes is somewhat of a detour from this arc in that he puts aside the opacity of images. In this sequence, the self-portrait on the light table reappears pinned on the wall and covered with Campeau’s notes and with scribbles by his son Léandre, whose hands and pencil we see as he gets busy making his father’s print his own. Mise en abyme and reprise in the form of quotation speak here of the limits to revealing the person and the failure of images to relate a reality other than their own materiality. Another self-portrait follows, this one in the darkroom, in which Campeau appears behind the massive structure of the enlarger that occupies and dominates the entire foreground. This same image, the object of a series of successive reprises and transformations, evokes Campeau’s work on photographic matter and blocks any necessary or definitive meaning that might be assigned to it, for Campeau puts it through multiple variations in his darkroom – a Plato’s cave, a realm of shadows, impressions, and opinions.

The snapshots drawn from Campeau’s family album to weave the narrative for …si je mens, j’irai en enfer! were gathered not to confront the past with the present and present the photographer as an other in the distance of souvenir images, but to recompose a symbolic genealogy in which the portraits of relatives and a few close friends are juxtaposed through free association with images gleaned in various cemeteries in the Montreal area. The narrative disappears, giving way to a series of visual metaphors each of which forms a whole turned in on itself, representing a decisive figure in Campeau’s career.

The figure of the photographer trying to wind up the thread of his life, show emotional connections, and explore family relations that dominated the autobiographical path gave way, in the early 2000s, to self-portrayal. In L’ombre de soi, Campeau took many pictures in which his shadow was projected on plants in a garden, marking the nature of his presence. From what is considered a fault in many amateurs’ snapshots he makes a symbolic motif, that of the photographer in absentia. The shadow becomes his double thanks to the ability of the photograph to convey the contrasts between the dark zones of the silhouette and the luminous luxuriance of nature into which it cuts; these images constantly oscillate between light and dark, between empty and full, between appearance and disappearance. The series Humus and Paysages métaphysiques place Campeau, dressed in black, in the frame in landscapes that are also inner territories. He inhabits the landscape and melds with the natural elements to the point of vanishing. What counts is only the photographic instant that records this intimate ceremony in which the author’s personality is wiped away, leaving room for the pure, concentrated presence of the photographer’s body and his figure as visual motif.

The Collector. Using snapshots taken by amateurs, adapting photographs from Robert Frank’s The Americans, and appropriating pictures from the family album of American scientist Rudolph Edse to compose the book Rudolph Edse: An Unintentional Autobiography,3 Campeau adds a chapter to his own story – that of the collector who, through the practices of other image producers, finds a reflection of his personal and professional concerns. An exercise in admiration as much as a reflection on images and their impact on the gaze posed upon them, these borrowings acquire particular resonance and raise a number of questions. Who is their author: the one who took them? Or the one who appropriated, passed them through the filter of another gaze, and revealed dimensions foreign to the intentions behind their production?

Even earlier, in Les tremblements du cœur, Campeau was integrating into the weft of his discourse, like so many quotations, pictures by photographers who had inspired him, such as Koudelka, Kertesz, Michaels, Gibson, Riboud, and Frank, through whom he re-created an intellectual family. The reconstruction, in the form of tribute, that Campeau has performed using Frank’s iconoclastic work is on this order.4 Frank’s pictures – with their skewed perspectives, surprising angles, and rough lighting that capture things as they’re happening, on the spur of the moment, without preparation or compromise – disrupted the generally accepted canons due to both their glorification of spontaneity and the banality of the subjects, which were deemed insignificant by serious photographers. They were not, however, insignificant to amateur photographers of the time: in the images chosen by Campeau, it seems that Frank borrowed some aspects of his subjects and approaches from the codes of vernacular photography that modulated the gazes and constituted the spirit of the times. As an experienced photographer, however, Frank inscribed these visual codes in a unique process and in a project with clearly formulated intentions. The link here is Campeau – his interpretation of Frank’s work and his vision of photography – who deals with mishaps by selecting them for their affinities and their thematic coherence as if they were fragments to be inserted within the continuity of a much vaster ensemble, that of the collection based on a relationship to objects which does not emphasize their functional, utilitarian value – that is, their usefulness – but studies and loves them as the scene, the stage, of their fate. The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership – for a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.5

The group of photographs by Rudolph Edse, for their part, evince the coherent personal vision and sustained visual quality of a talented photographer, well versed in the characteristics and possibilities of the medium, and the shots bring to a rare degree of perception the characteristics of vernacular photography. In Edse’s production we find the same motifs as in Campeau’s: family and the ties that bind its members, daily activities, the presence of the living environment, the rituals of posing and of taking the picture, and above all, the omnipresence of the photographer, his work, and his tools. “I have conflated myself with the parental figure of Rudolph Edse – his self-taught practice, his involuntary autobiographical quest, his compulsion with appearing in his artistic attributes, his chivalrous soul, his melancholic gaze, and the people who came to affectionate encounters.”6

In this process of identification with Edse and of projection of the self into a memory space that belongs to someone else, the image becomes a screen on which Campeau projects his own experience and examines the truth of his practice. We are no longer, here, in the autobiographical mode or in the symbolic register of works in which the photographer places himself as an other, but in the elucidation of conditions for producing images through the figure of the photographer’s tools and the reconstruction of a continuity in the distanced gaze of an alter ego in which Campeau finds and moves into himself. It is this migration of images of one conscience to another that enriches them. For the image exists only in a beam of gazes that break through the surface and project into it their knowledge, desires, concerns, and questions. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Michel Campeau, “The Donkey that Became a Zebra,” in Campeau, Carrière, Clément: Accumulations (Montreal: Éditions Simon Blais, 2015), n.p (our translation).

3 Michel Campeau, Rudolph Edse: An Unintentional Autobiography/Une autobiographie involontaire (Paris and Montreal: Les Éditions Loco and McCord Museum, 2017).

4 This project was also the subject of a video presented during the exhibition: Romain Guedj, director, Michel Campeau – Revoir Les Américains de Robert Frank, 2018, 18 m, 43 s.

5 Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 60.

6 Michel Campeau, introduction to the exhibition section devoted to Rudolph Edse’s photographs.

Pierre Dessureault is an expert in Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized some fifty exhibitions, published catalogues, contributed to books, and written a number of articles on photography. Since his retirement, he has devoted himself to studying international photography in a historical perspective and, reviving his early interest in philosophy and aesthetics, to exploring in greater depth the theoretical approaches that have marked the history of the medium.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 110 – MIGRATION ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Michel Campeau. Photography, the Photographer, the Collector – Pierre Dessureault ]