[Winter 2019]

By Stephen Horne

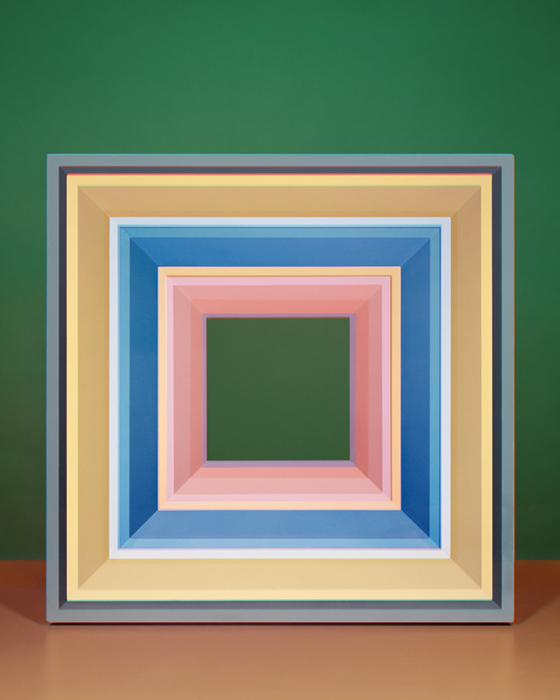

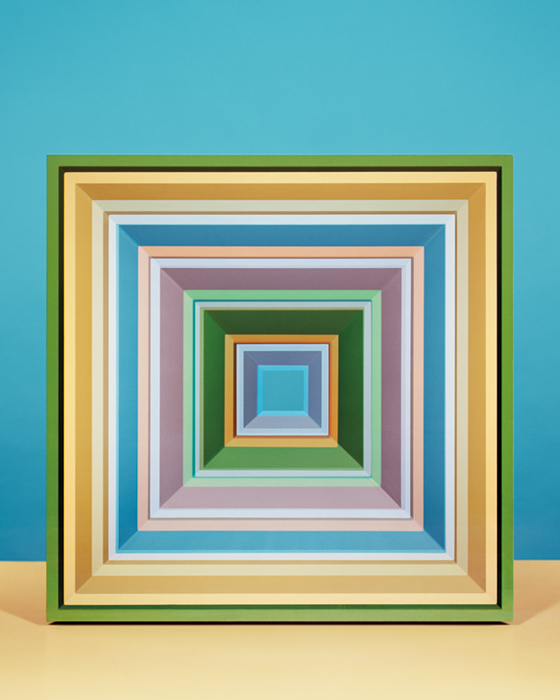

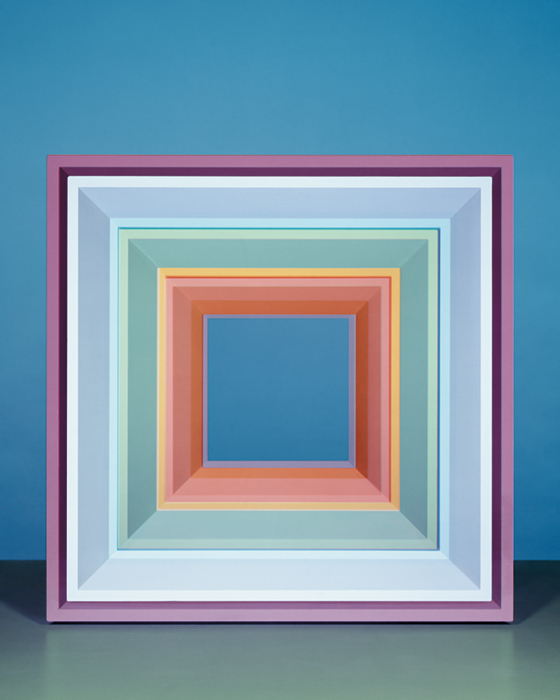

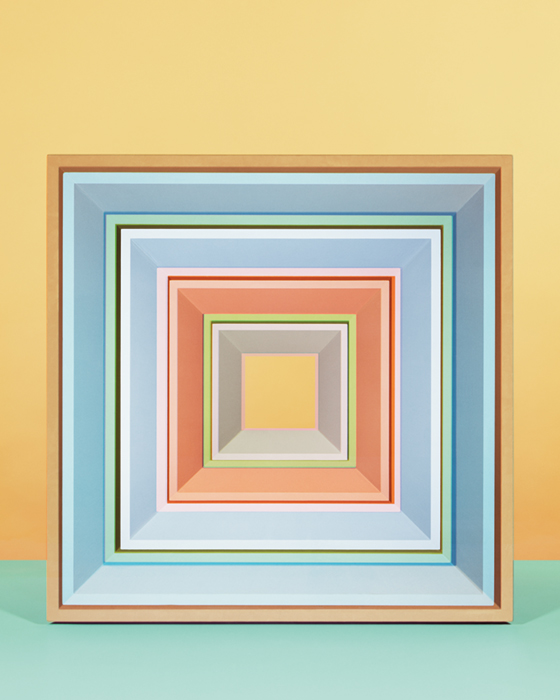

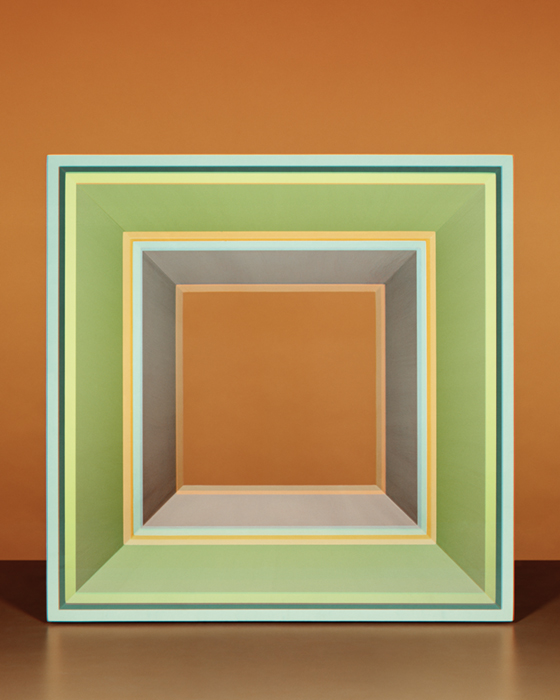

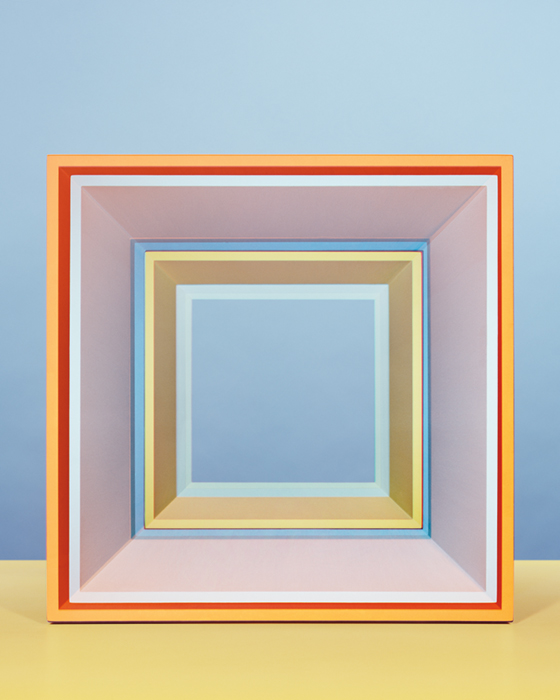

A number of Montreal artists are proposing ambitious responses to the dissolution of traditional artistic genres in what is clearly a “post-medium world.” Jessica Eaton is one of these, as evidenced by her recent exhibition titled Iterations (I) at Galerie Ertaskiran. In this exhibition, we face a long wall of what initially seem to be abstract and sensuously beautiful paintings. These intensely formal mid-size framed rectangles are characterized, however, by an ambiguous feeling of systemic origin. This initial perception is also qualified by the illusionistic space in which frames within frames recede toward a vanishing point. These frames could also be described pictorially as boxes, and this possibility is reinforced by what appears to be a horizon against which the frame/box object is posed. In this sense, we could say that in this fictional space there is a box within which other boxes are enclosed, the entirety resting on a surface with a wall behind.

Close attention to just a few images allows for some initial considerations. For example, these particular images are composed of rectangles nested one inside another diminishing toward a centre, or potential vanishing point. These bands of colour function systematically to differentiate aspects of a plane rather than the painterly expressivity that we might find were these actually paintings. That is, there is a sense of distance and non-attachment that suggests an origin deriving from the predetermined processes so well demonstrated by the original conceptual artists, such as Sol Lewitt. These inspirations arise from outside the traditional artistic bases of human perception and handcraft.

A number of Montreal artists are proposing ambitious responses to the dissolution of traditional artistic genres in what is clearly a “post-medium world.” Jessica Eaton is one of these, as evidenced by her recent exhibition titled Iterations (I) at Galerie Ertaskiran. In this exhibition, we face a long wall of what initially seem to be abstract and sensuously beautiful paintings. These intensely formal mid-size framed rectangles are characterized, however, by an ambiguous feeling of systemic origin. This initial perception is also qualified by the illusionistic space in which frames within frames recede toward a vanishing point. These frames could also be described pictorially as boxes, and this possibility is reinforced by what appears to be a horizon against which the frame/ box object is posed. In this sense, we could say that in this fictional space there is a box within which other boxes are enclosed, the entirety resting on a surface with a wall behind.

Close attention to just a few images allows for some initial considerations. For example, these particular images are composed of rectangles nested one inside another diminishing toward a centre, or potential vanishing point. These bands of colour function systematically to differentiate aspects of a plane rather than the painterly expressivity that we might find were these actually paintings. That is, there is a sense of distance and non-attachment that suggests an origin deriving from the predetermined processes so well demonstrated by the original conceptual artists, such as Sol Lewitt. These inspirations arise from outside the traditional artistic bases of human perception and handcraft.

In fact, Eaton has herself stated her interest in “see[ing] in ways outside of our perception.”1 This could mean seeing in mystical or visionary terms, or it could mean seeing understood as something potentially subject to calculation – that is, by way of the iterative prostheses of algorithmic culture. About a year ago, Toronto art writer Adam Lauder published an article in which he discussed light as presented in the works of various Canadian artists. Eaton’s work was one of his topics. Pursuing the view that Eaton’s productions are “making themselves,” he argued that they are “quasi-automatic manifestations of an inaccessible real… rather than a representation of the world.”2 Eaton has quoted Lewitt’s celebrated maxim “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art,” but this could also be read in reverse – “the machine becomes the idea that makes the art” – and juxtaposed against a prescient passage by Kafka, “Now just have a look at this machine. Until now a few things still had to be set by hand but from this moment it works all by itself… it’s a remarkable piece of apparatus.”3 Side by side, these two excerpts propose that we ask again how meaning is made and for whom it can exist.

Eaton’s fabrications – I say that not being sure whether to call them images, objects, fictions, compositions, or designs – float in an in-between space, neither painterly nor photo- graphically mimicking a worldly subject in front of the camera. In such cases, we would normally have recourse to a back-story that would somehow locate the art for us. In Eaton’s case, this resides in a narration of the artist’s processes, which are of the traditional sort from outside photography itself, procedures involving handcraft. The camera is itself a key element in this story, which includes painting’s historical displacement by a machine.

Eaton proposes that we ask ourselves what a camera is and where its talent resides. Part of her own answer to these questions is that the camera is a prosthetic process and that this process is concerned with capturing, ordering, and recording natural light, the origin of which we would experientially situate in the sun. Part of our being human is our sensory capacity to apprehend this light, or some range of it anyway, and we might want to say that there is light because we can perceive it, and to extend our capability we have prostheses, and these prostheses in turn inform and frame our vision.

In any case, Eaton involves herself, and us, with such reflections. The referent tends to be situated within the technics of image making, in which the image is perpetually in production and circulation without ever touching down, neither as material being nor as reproduction. This is the site of the referent’s production, and it is precisely the conventional camera and its technical procedures that form the basis for Eaton’s process, which consists of interventions in the camera program – interventions that reverse what traditionally have been an outside and an inside of the apparatus. We would, on this basis alone, call her work “abstract” or “research based,” and on the basis of the non-referential style of her work we would in the art context align her with the early modernist artists, especially those explicitly involved with practices of technical experimentation, such as Lazlo Moholy-Nagy.

In the current series, Iterations (I), there is an apparent reference to the vastly influential series of paintings created by Joseph Albers in the 1950s and 1960s titled Homage to the Square. This series was considered “rigorous” in many contemporary accounts, but those on the scientific side contested his observations concerning the interaction of colours. The arguments proceed from differences of perspective: Albers’s notions were primarily perceptual and experiential, whereas his critics favoured an analytic basis for their position. In any case, Eaton invites us to regard Albers as some kind of marker for her concerns by adopting his format of exploring chromatic interactions within sets of nested squares.

Thanks to the sun, there is light, and light is matter, and, materially speaking, there are light waves, and using our prostheses we can measure these waves, some of which are outside the range of human perceptibility. A few of the names for these light waves are familiar. For example, we know radio waves, microwaves, gamma rays, ultraviolet rays, infrared rays, and x-rays. There are others, less familiar, but the point would seem to be that only a small range are immediately accessible through human perception, whereas others we “know” through our prostheses. Many of these prostheses are not tangible but consist of systems, including culture. Eaton avails herself of certain prostheses, including the camera device itself, but also of the sorts of systems we use to organize and formularize our perceptions, which otherwise tend to be comparatively anarchistic. These systems are sources of authority, operations that we use to bring nature into line with our human needs. What is most interesting is the paradox involved. Eaton uses analogue procedures and tactile perceptions in her initial labour-intensive process but also adopts the algorithmic process as the model for her practice. Algorithms are abstract, symbolized, step-by-step instructions normally written in code and expressed in the forms called software or programs. Hence the title of this exhibition: Iteration (I). Working with this process is both Eaton’s motivation and the source of her relevance to the post-medium viewer.

The founding ambiguity presented with Eaton’s project directs us to consider Laura Mark’s observation regarding visuality: “I personally think that the period of visual culture is over… information culture, which is invisible, is becoming the dominant form of our culture.”4 On the one hand, Eaton presents the aspect of art’s continuing dematerialization; on the other hand, she maintains by way of her back-story the perspective of authorship and the handmade sensuous object – the aesthetic and ethical realm or guide to which the contemporary art world continues to refer as a primary authority. It is the tension that she evokes between traditional authorship and the now-prevailing “information culture” that is the source of her considerable pertinence to our moment.

2 Lauder, “Photogenesis,”, 77.

3 Franz Kafka, “The Penal Colony,” in Collected Stories (New York: Knopf, 1993), 131.

4 Laura Marks, “Interview,” in Margaret Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture: A Study of the Visual After the Cultural Turn (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 215.

Stephen Horne is an independent curator and writer living in Montreal and France. He has taught at NSCAD and Concordia Universities and is published in periodicals, catalogues, and an- thologies in Canada and elsewhere.

Jessica Eaton was born in Regina, Saskatchewan, and she lives and works in Montreal. In her abstract photographic work, she explores the conditions of photographic vision and representation. Her work, long recognized in Canada and abroad, has been in numerous individual and group exhibitions, won distinctions, and been the subject of articles in major magazines. She is represented by Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran in Montreal, and by Higher Pictures (NY) and M+B (LA). jessicaeaton.com

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Jessica Eaton, Iterations (I) — Stephen Horne, System or Poem? ]