[Winter 2019]

By Érika Nimis

Every summer since 2010, Les Rencontres internationales de la photographie en Gaspésie has literally pushed art photography into parks and forests and onto beaches, inviting visitors to a true treasure hunt along the legendary Route 132. During each edition, this photographic and human adventure is punctuated by a number of public events: screenings, discussions with the artists, book launches – all in a friendly, intimate atmosphere that encourages conversation, unlike the “high masses” of photography.

In an updated setting,1 the ninth edition of the event,2 with the theme of chaos, presented fifteen exhibitions, five of which resulted from art residencies initiated by Les Rencontres. Providing a counterweight to shocking photojournalistic images, the coherent selection for this year explored the traces of chaos that mark territories shaped by both the convulsions of history and the backwaters of capitalism.

In Quebec, this chaos, often experienced as subterranean, haunts northern Indigenous territories. Director Éli Laliberté travelled through these areas, shooting a “video road trip” to be used in a play, Philippe Ducros’s La Cartomancie du territoire, presented in Montreal in spring 2018. A public reading of an excerpt of the “hardline” play took place in Carleton-sur-Mer on the evening of August 17, accompanying Laliberté’s images of the damage done to these lands. On the same subject, Elena Perlino used a humanist documentary approach to highlight the resiliency of the Innu and Naskapi, to whom she paid homage in a photographic series accompanied by a video shot over the shoulder, Indian Time; these works were presented first in Gaspé, and then in Matimekush-Lac John and Montreal as part of the satellite programming.

Still in relation to the “subterranean chaos” sustained by a long history of exploitation of territories and communities, for her series Le vent est tombé, presented in Caplan, Myriam Gaumond explored Murdochville. This mining town, which had its moment of glory from the 1950s to the 1970s and became a ghost town in the 2000s, is now converted into a ski resort in wintertime. Murdochville may be empty of life today, but this desolation is softened by a nostalgia for better times, embodied in the stories and family photographs that the miners’ wives shared with Gaumond.

Other places, other kinds of chaos. In Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay (2016), presented in Percé, Debi Cornwall, formerly a civil-rights lawyer, presented her unvarnished scrutiny of the underside of the media setting for the now sadly famous military base. Despite drastic censorship, she managed, through meticulous research and subtle detours, photographing places and objects that seem unspectacular, to show the hell of imprisonment (a “feeding chair” for hunger strikers, a screening room for “model prisoners”). Her main goal is to rehabilitate the innocent people shattered by their arbitrary detention, whom she was able to meet and photograph (from the back) once they were freed.

In Parc de Forillon, Nadav Kander developed an “aesthetic of destruction” with his colour series Dust (2014), a project produced in the post-apocalyptic setting of the Semipalatinsk polygon in Kazakhstan, the site of nuclear tests in the 1950s and 1960s. The site is now home to the military town of Kurchatov, contaminated and partly abandoned, as if frozen in the Cold War era.

Since 2014, Youri Cayron and Romain Rivalan (Demandez aux oiseaux, presented in Paspébiac) have been highlighting urban-planning aberrations in Israel and Palestine, where architecture is a tool for both survival and oppression. In this land of migrations, the birds, paradoxically, are the only living things not subjected to borders, and as a consequence they have access to all versions of the history on both sides of the wall.

Physical and mental borders that generate chaos were a recurrent theme in the works presented, so much so that a connection is woven, a dialogue established, among all the exhibitions visited. In Chandler, Daniel Schwarz’s installation, inspired by his accordion book (presented in late 2017 in the exhibition Frontera at the Canadian Photography Institute), a reconstruction of the United States– Mexico border compiled from Google Maps satellite images, is literally spread at our feet, like a spine, inviting us to cross it, walk along it, and reflect on it. On the same subject, Andreas Rutkauskas’s series Borderline (in New Richmond) documents the surveilled no-man’s-land along the longest terrestrial border in the world – the one between the United States and Canada.

Whereas Google’s satellites allow artists to see the infinitely big, other techniques, such as photogrammetry, enable them to examine the tiniest spaces. The poetic and experimental offerings of François Quévillon (Météores), presented at Parc de Miguasha, are the result of an in situ residency in which the artist took an “interplanetary” voyage to the region’s geological landscapes. In a different vein, Mathilde Forest and Mathieu Gagnon, in Red Hook: fragments et empreintes (in Bonaventure), appropriated this technique for their examination of the transformation to the architectural heritage of an industrial Brooklyn neighbourhood being gobbled up by developers. In Stratotype Digital-ien, Isabelle Gagné, a “geological artist” from the digital world, breathes chaos into Quebec landscapes using a computerized autonomous robot that randomly recomposes images of landscapes compiled through a collaborative digital apparatus. The result is a booklet for each of Quebec’s seventeen administrative regions.

Diametrically opposed to Gagné and her digital experiments, but just as adept at “photographic extremes” and also presented in the Vaste et Vague artist-run centre in Carleton-sur-mer, Martin Becka makes his negatives, photographs with a large-format view camera, and prints in his darkroom. All, slowly. During his residency, he went along the section of train tracks between Matapédia and Gaspé, unused since 2013, which has been gradually invaded by weeds. He thus revisits the story of the railway by linking it to both economic history and the history of silver-halide photography.

In Marsoui, Janie Julien-Fort also revealed, in a way that was random, wild, and poetic, the chaos generated by mercantile interests by installing “spy pinhole cameras” at construction sites in Montreal to record how they advanced over several months. The resulting latent images (Paysages éphémères) refer to the fragility of the urban environment, as does the presentation device (one of the most striking, along with Schwarz’s): an alley of printed flags at the mercy of the wind’s ire.

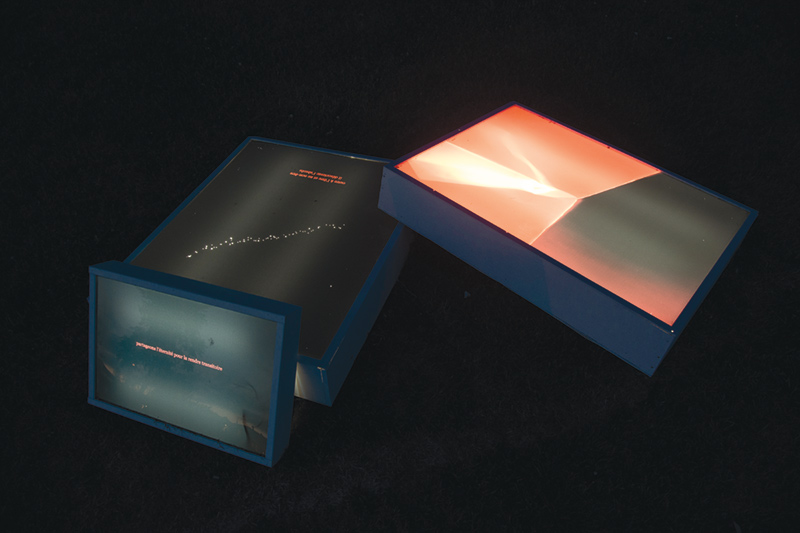

Last but not least, Fiona Annis’ installation Perdre le nord (in Maria), made of fragments of falling stars (materialized as light boxes on the ground), offers a meditation that is both poetic and metaphysical on the chaos of our inner existence. Starting from a single sheet of photo-sensitive paper crumpled and exposed to the light, then developed, Annis explores the fissures and scars in our memories, in light of writings by Maurice Blanchot (particularly his essay L’écriture du désastre, published in 1980). And the circle of chaos is closed. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The event was held from July 15 to September 30, 2018.

Érika Nimis is a photographer, Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Rencontres internationales de la photographie en Gaspésie. Traces of the Chaos — Érika Nimis ]