[Winter 2019]

By Pierre Dessureault

The exhibition Camerart, produced by Galerie Optica and presented in Montreal from December 16, 1974, to January 14, 1975, was a pivotal event in the photography/art debate in Quebec. Although a place in the art market had been carved out for photography in the late 1960s, museums were proceeding more cautiously. Across Canada, certain national institutions were mandated to collect and display contemporary Canadian photography, including the National Gallery of Canada and the Photography Service of the National Film Board. The former focused on what, at the time, was called art photography or creative photography, which involved image autonomy and specific production protocols. The latter, directly descended from the interventionist tradition promulgated by John Grierson, fell within the current of documentary photography that scrutinized the present. Thus, the Photography Service was seen less as the repository for a collection than as an active participant in production of the photographs exhibited at its Image Gallery in Ottawa (inaugurated in 1967) and published in a series of books on Canadian photography.

In Montreal, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM) still favoured traditional forms of art and left room for multimedia works and photography only in thematic group exhibitions. One example at the MMFA was Montréal plus ou moins (1972), conceived by curator Melvin Charney as a vast multidisciplinary display bringing together photographs, all kinds of documents, and conceptual works to offer a critical gaze at the city. At the MACM, Périphéries, organized in 1974 by Alain Parent, gave an overview of the diversity of current production by the member artists at Véhicule Art. The intention of Normand Thériault, who curated Québec 75, was to go beyond a compendium of individual practices to offer a portrait of the energy of the art milieu building in Quebec. And we mustn’t forget Corridart, organized for the Montreal Olympic Games of 1976, which prominently featured photography in many of the installations deployed along Sherbrooke Street – and was censored by the municipal administration.

In the early 1970s, in response to the demands of a generation of artists dissatisfied with the “museum-bound” art promoted by established institutions, a network of parallel galleries sprang up to provide a dissemination channel specifically for artists whose alternative practices included multidisciplinary and pluralistic approaches. Galerie Optica and Véhicule Art (Montréal), both founded in 1972, were the first artist-run centres (as they came to be known) in Montreal. Véhicule was to make Land Art, performance, conceptual art, and media art its warhorses. Optica, originally called Galeries photographiques du Centaur, would position itself as a promoter of photography of all types. Between 1972 and 1974, it produced exhibitions featuring current production by, among others, Gabor Szilasi, Sam Tata, Michel Saint-Jean, Charles Gagnon, Tom Gibson, Sylvain Cousineau, Robert Bourdeau, Michael Flomen, Michel Lambeth, and John Max, as well as documentary photographs by GAP, GPP, and Clara Gutsche and David Miller. International artists included Tony Ray-Jones, Lee Friedlander, Eikoh Hosoe, Roman Vishniac, and Edward Muybridge, as well as group exhibitions on themes such as French families seen by the Viva agency and the influence of Alexis Brodovitch.

The change in name from Galeries photographiques du Centaur to Galerie Optica in 1974, like presentation of the exhibition Camerart, signified a broadening of the gallery’s original mandate by adding eclectic works by contemporary artists to those by photographers. Bill Ewing, director of the gallery and instigator of the project with artist Robert Walker, clearly situated the intention: “Camerart is an attempt to focus further attention on this relationship by bringing into a gallery of photography a number of artists who incorporate photographic ingredients yet do not consider themselves to be photographers. . . . While the twenty-four contributing artists have little concern with the preoccupations, precedents, and standards of photography as a tradition sui generis, their works are not to be taken as negations or denials of this tradition. Rather, their interest in photographic processes results from an entirely separate intellectual tradition – art history.”1

For the artists in Camerart,2 many of whom were members of Véhicule, photography was merely one tool among others, and the camera was an impersonal, neutral machine that made it possible to produce and reproduce images, short-circuiting work done by hand and the expertise upon which traditional art production was based. Some artists treated photographic images as raw materials to be taken up and integrated into a hybrid ensemble by means, notably, of non-photographic processes, returning them to circulation in compositions or assemblages. Michel Leclair, for instance, used serigraphy to transform photographic images into signs of working-class culture or Ti-Pop accents. In her etchings, Jennifer Dickson incorporated photographs into feminist discourse by diverting classical imagery and juxtaposing it with a celebration of female sensuality. Charles Gagnon employed the cyanotype process as a means of structuring a pictorial space. In Gagnon’s case, the use of old processes to meld photographic images into an original visual totality by transposing them into another medium conferred a new materiality on the structure by preserving characteristics resulting from their production protocols.

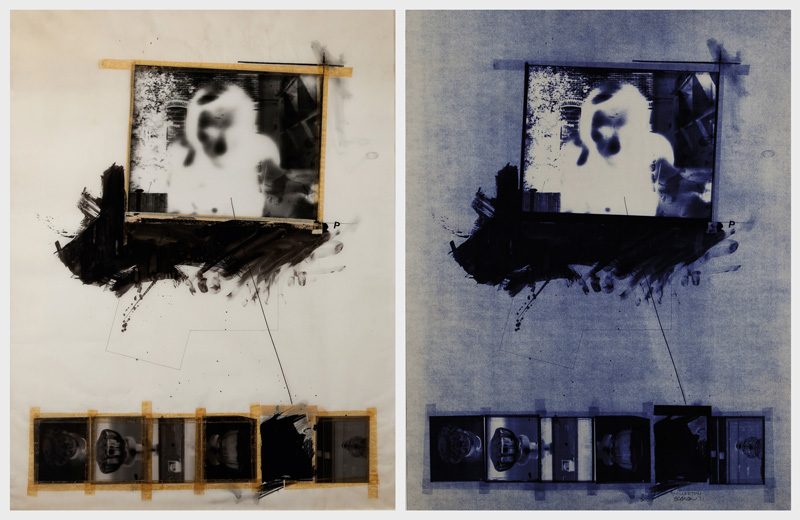

If the autonomy and uniqueness that pure photography conferred upon the image were demolished, then all production in the medium was equally valid and the print became simply a surface – a support for interventions made with other art techniques, such as drawing, painting, and collage, which marked and altered its meaning. Christian Knudsen manipulated images with a combination of photographic emulsion, acrylic paint, adhesive tape, and pencil lines to create composites in which each technique underlined or modified a motif to create a representation that was the sum of all of these techniques, each adding its own expressive register to the ensemble. Irene F. Whittome, for her part, was interested in gesture and its portrayal, and she juxtaposed in a single image two versions that had been revised and corrected by drawing. The creative act, seen as a series of interventions, became the subject of the artwork. It was brought to fruition in three images, marked by the artist’s successive additions, that remade the story of its trajectory.

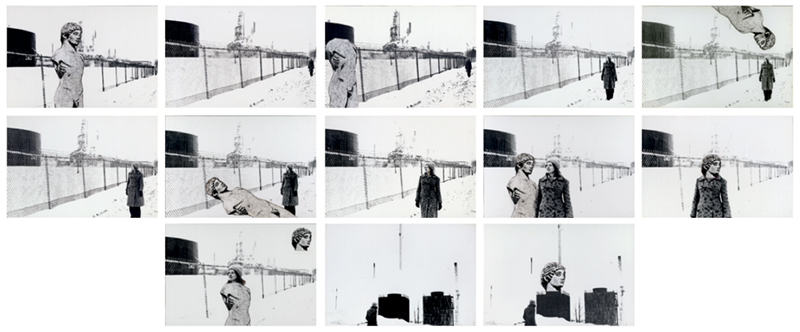

The infinite reproducibility of the photographic image opened the door to seriality, and thus to compositions in which its meaning was found no longer in a hermetic singularity but in the series within which it was inserted. Using strategies such as repetition, sequence, grid, and juxtaposition, artists arranged images in relation to others to form groupings that could be read in the flow of the spectator’s gaze. In an exploration of identity, Suzy Lake created a grid of ninety images on which she traced the gradual transformation of her white-painted face as she traced a new physiognomy on it. Her performance was displayed for and by an unmoving camera that recorded not only the traces intended to make a permanent record of her gesture, but the process brought to light by the continuity of events. In the recombination through which Lake played on the representation and transformation of her identity, it was all of the links within which the image was inscribed that became singular and unique. Françoise Sullivan composed a frieze that offered an unfolding narrative based on three figures: the strolling artist, a reproduction of a statue of Apollo, and the oil refineries in the east end of Montreal, which served as the setting. A back-and-forth relationship was established among these three motifs: their configurations shifted as the artist moved around, so that her path was transformed into a trajectory between the ideal of Antique beauty and the modern industrial structures that were putting the balance of nature at risk.

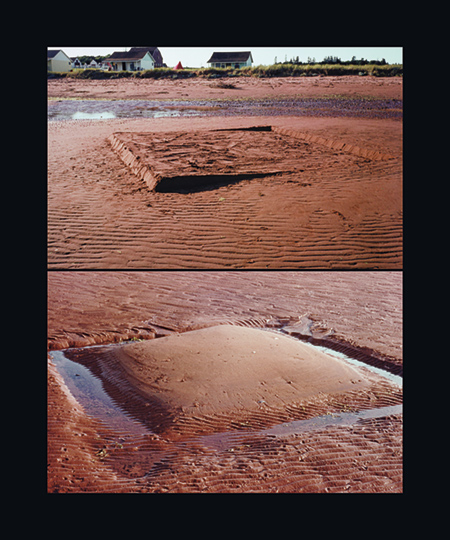

The capacity of photography to extract instants from visible movement in order to record them and give them form was fundamental to the work of Serge Tousignant and Bill Vazan. By photographing multiple points of view of a cube drawn with adhesive tape in a corner of his studio, Tousignant frustrated the classical perspective based on the fixity of vision and established, in a grid that acted as a unifying principle, a series of anamorphoses organized and fixed by the photographic framing. Vision thus depended on both the camera and its operator, who subtracted a fragment of the visible. Vazan’s drawings in the sand of a beach in Prince Edward Island, destined to live only as long as the next tide, were torn away from the ephemeral and rendered permanent in the form of images that went well beyond simply recording the artist’s intervention in nature. The framing of the tracings in the red sand, the palette of shimmering colours, and the plays of light on the textures of water and sand are all visual characteristics of the medium that both marked the rendering of the print and magnified the portrayal of the artist’s gesture.

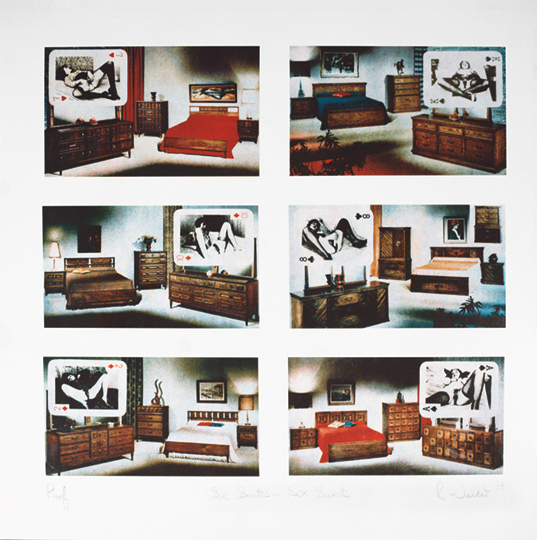

Robert Walker and Jean-Marie Delavalle produced radical reflections on life and the production of images. Walker used emblematic portrayals of working-class culture as raw materials, appropriating and recontextualizing them to reveal their hidden meaning. The coexistence of generic photographs of middle-class interiors and reproductions of a deck of pornographic cards in a new visual space created by the artist had shock value and denounced the status of advertising imagery, which, though glossy and anonymous, nevertheless transmitted social values. Subverting images by turning them upon themselves, he created a critical distance in an attempt to shield them from ideology by “the only possible rejoinder, [which] is neither confrontation nor destruction, but simply theft: fragment the old text of culture, science, literature, and change its features according to formulae of disguise, as one disguises stolen goods.”3 Delavalle’s slide show was part a group of works in which he inventoried the systematism of the photographic apparatus. After methodically reviewing the framing, focus, materials, and apparatuses that structure the gaze and its transposition into image, he concluded his cycle of studies by featuring, with slide projector and sound track, the projection mechanism itself, which acquired autonomy through an automatic timer – an integral part of the projector. Just as the photographic apparatus constructed the artist’s gaze, the mechanism of the projection structured the spectator’s perception.

In thwarting the specificity of the medium and questioning the transparency of its representations – the foundation of pure photography and its social aspect – the artists in Camerart put into play a panoply of forms that updated the full potential of the photographic apparatus and counted on its ambiguous status, as it both imprinted its mechanical qualities on images and borrowed from the aesthetic categories of art history. In doing this, without questioning the legitimacy of the photograph and its apparatus as a tool for art production, these artists subjected the very status of art and its tradition to critical examination. In this sense, the exhibition displaced the debate on the relations between photography and art. The question was no longer whether photography had the capacity to portray the world and its relations with the art of its times or whether or not it belonged to the domain of art production – a debate that stretched back to the nineteenth century – but whether photography was a medium that art, in its contemporary iteration, could annex as a production protocol, the logic of which made it possible to create signs that would compose an original text to decipher. In this sense, we might ask, with Walter Benjamin, whether, with the invention of photography, “the entire nature of art had changed.”4 Translated by Käthe Roth.

2 Aside from the works discussed in this essay, the exhibition presented works by Jan Andriesse, Allan Bealy, Pierre Boogaerts, Eva Brandl, Tom Dean, Gloria Deitcher, François Dery, Michael Haslam, Stephen Lack, Kelly Morgan, Nancy Nicol, Jean Noël, and Gunter Nolte.

3 Roland Barthes, Sade, Fourier, Loyola, trans. Richard Miller (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989),

10.

4 Walter Benjamin, “L’œuvre d’art à l’époque de sa reproductibilité technique” (1939), in Sur la photographie (Paris: Éditions Photosynthèses, 2012), 174 (our translation).

Pierre Dessureault is an expert in Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized some fifty exhibitions, published catalogues, contributed to books, and written a number of articles on photography. Since his retirement, he has devoted himself to studying international photography in a historical perspective and, reviving his early interest in philosophy and aesthetics, to exploring in greater depth the theoretical approaches that have marked the history of the medium.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Camerart. Art from the Point of View of Photography — Pierre Dessureault ]