[Winter 2020]

Demonstrations. From Occupy Wall Street to Extinction Rebellion actions, popular resistance demonstrations have become an integral part of international news over the last decade. We are almost accustomed to seeing, over and over, spectacular images of uprisings against dictators, altercations among citizens, identity-related confrontations, movements of crowds in war and in desperate migrations. The dynamic of these crowds varies considerably, from pacifist marches to violent riots. Such waves of movements have punctuated the daily news diet on every continent – during a period of undeniable acceleration in the pace of global current events.

Samplings. From day to day, dozens of photographs of crowds accumulate. After a few years, there are thousands of them. Gradually, the images are decontextualized, shedding legends and metadata and then being grouped as a function of scale, density of crowds, farthest to closest, then people’s positions, varying among frontal, profile, and back views. With the information removed, these images become equivalent and replaceable.

Starting from the difference between a group of unique individuals and a crowd within which they are anonymous, these images are at the pinnacle of sampling. The suppression of singularity in the typology of accumulated units corresponds to the negation of the uniqueness of individuals in a population.

The photographs come from outdoor urban spaces all over the world. They are essentially street scenes, many taken during political demonstrations. Then, given the effect of loss of distinctions due to massive assimilation, both in the photomontage and in the demonstrations, the collection of photographs is broadened through examination of diverse contexts: national celebrations, festivals and carnivals, religious and sports events, and any other kind of possible assembly. Whatever their stated purpose, these demonstrations remain political events, explicitly or not.

Cutting out, assembling. From these images, we first cut out details, in square format, that were then assembled in a grid. This systematic organization of the photomontage is considered with a view to the historical dimension of the documents used. We are reminded, here, of a reference text by Rosalind Krauss on the structure of the grid: “One of the most modernist things about it is its capacity to serve as a paradigm or model for the antidevelopmental, the antinarrative, the antihistorical.”1

The reframings generally delete the information that would enable us to recognize the contexts of the demonstrations and the ideologies represented in them, as they cannot explicitly denote the cause of the gathering. They avoid architectural and roadway elements that would make it possible to situate the provenance of the images. The more radical rub elbows with the more moderate, left wing with right wing, and it’s impossible to say which is which.

The law and image appropriation. Making modifications to source images requires an approach that reflects current copyright and image rights practices. Court precedents may set the legal limits for use of portions of images in a photomontage, but the boundaries are not clear. Starting from cases in which certain appropriations are understood as negligible, one concludes with a very relative interpretation of the de minimis doctrine, considering that it is almost impossible to find the sources in the present case, due to the number of details and the digital processing to which they were submitted. The recutting of thousands of fragments will have produced more than ten thousand units altogether.

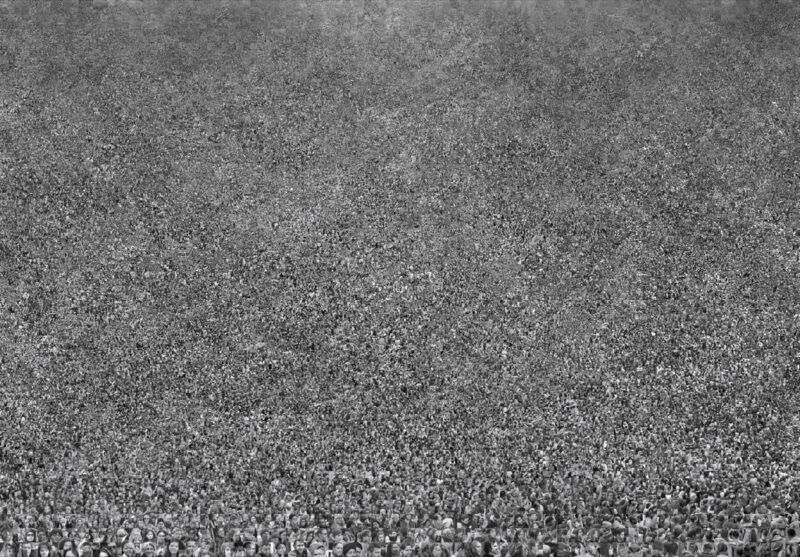

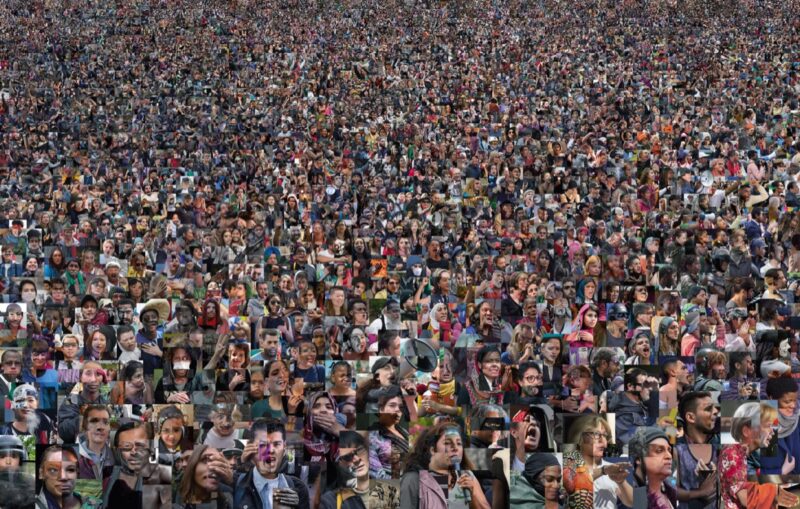

Two tableaux. Although the initial plan was to group all the images on a single surface, the process ultimately produced two large tableaux that are different but related: Masses/particules and Grand rassemblement (vive la sociale).2

Comparable: The tableaux have a single compositional structure, melding a flattening and a false perspective through the creation of tiers and modulation of the scale of the units in the grid. The improbable bird’s-eye views combine high, oblique, and horizontal angles. From a great distance to very close, the crowd is marching toward us. All the actors are aligned in the same direction, gradually turning toward the right side of the image. Direction unknown.

Different: The grid structure is constant in Masses/parti cules, whereas it is variable and gradually crumbles in Grand rassemblement. One, in black and white, draws on the loss of individual singularity in the mass, whereas the other, in colour, exaggerates the expressiveness of the demonstrators. In the first, the hand signals or specific expressions disappear in the crowd, whereas in the other, these elements of significance accentuate the dramatization of the composite crowd.

Masses/particules. We are looking at more than a million human heads, the sizes of which vary from the head of a pin at the top of the image to a bit more than five centimetres at the bottom.

From a distance, we lose sight of the motif of a disproportionate number of people, whose legibility is absorbed in variations of grey. Other figurative possibilities are produced. It’s a bit like watching thousands of insects without understanding how they are organized. The mass is pulverized in a swarm of countless particles. It becomes a hallucinatory texture, a random movement of dust, a weather map, a celestial evocation. Or an energy substance.

Who or what do we recognize in the human mass?

All-over. Lots of people. Exponentially, it becomes the whole world. Through a continuous proliferation from edge to edge, it evokes the entire population of the globe, situated beyond the frame, of which we see here only a tiny proportion. The tableau is an all-encompassing spatial pattern without any definitions except its borders. It is literally an everywhere, evoking everyone. It refers to Edouard Glissant’s whole world,3 which brings up the ideas of co-presence and the interpenetration of cultures and imaginations in a globalized world. The whole world is this globalized reality and at the same time the vision of it that one might have.

Grand rassemblement (vive la sociale). In Grand rassemblement, the pixel-squares of the mosaic become rectangles whose irregularity evolves with the increase in scale of the characters toward the bottom of the image. From closer, the faces are life size. At a distance, they are only dense groupings, entangled clusters.

In the twenty-first century, social tensions are still based on non-recognition of the other and then rejection of the other’s difference. The photomontage mixes up everyone, integrating all differences with hybrid physiognomies – women, men, of all racial definitions.

More and more cities are currently installing hundreds of thousands of coordinated cameras for the purpose of facial recognition. Such hyper-surveillance is implicitly indicated in this work.

Masks. The collage of heterogeneous sources challenges individual expression and the physiognomy defining human uniqueness.4 We are seeing a “masked ball” of invented features. Sometimes grotesque, almost always dramatic. Citizens are angry, crying, laughing, kissing, in prayer and in violence. The extras have become actors, with queer, miscellaneous masks, sometimes mixing smiles with anger, anxiety with bravery. They are as credible as they are fictional. One might come across them in a cosmopolitan city.

We are approaching the tragedy of synthetic characters in a fictional uprising.

This bringing together so many individual expressions in an allegorical social scene is reminiscent of certain famous paintings by Bosch and Brueghel.

Causes. Although some are shouting through megaphones, the collage remains both silent and talkative. The picket signs and banners are out of frame. No text tells us what is motivating the people. For a century, the megaphone has been part of the iconography of demonstrations. It is metonymic. The tool of propagation of the people’s speech becomes its symbol, personifying its expression.

The subtitle “Vive la Sociale” refers to a 1888 painting by James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels, of similar dimensions. At the top of the painting, a banner bearing this slogan is stretched above a crowd of people many of whom are figured as clowns. At the time, the expression “La Sociale” conveyed the project of a citizens’ republic. Ensor’s painting portrays a carnival of masks and causes combined, topped by the ultimate cause, “Vive la sociale,” the battle flag of communitarian democracy. Treated with mockery and ridicule.

People coexist by assembling, in the montage of images as well as in the social body. They have come together for an unidentified “common cause.” What condition might be shared by all the individuals gathered here, including people for and against all kinds of issues, if not the global upheaval in the environment? The climate crisis is, above all, a human crisis. The prospect of its consequences is core to the project.

Beyond a possible cynicism, as suggested by Ensor, we will have chosen to come closer. By trying to resist media representations that degrade peoples.5 To situate ourselves in the world, with empathy.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Masses/particules, exhibition at Galerie Hugues Charbonneau, Montreal, September 5 to October 12, 2019.

3 Edouard Glissant, Traité du Toutmonde (Paris: NRF, Gallimard, 1997).

4 Hans Belting, Faces, une histoire du visage (Paris: Gallimard, 2017).

5 Georges Didi-Huberman, Peuples exposés, peuples figurants (Paris: Ed. Minuit, 2012).

Alain Paiement delves into relations between ordered structures and chaotic phenomena at various scales, from micro to macro. His pluridisciplinary projects are based on methods influenced by geographic science. His works have been included in numerous national and international exhibitions since the 1980s. More recently, he participated in the exhibitions Lost in landscape at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto (Italy) in 2015, and There all is order and beauty at Argos, Centre for Art and Media, Brussels in 2019. The Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal presented his project Bleu de bleu in fall 2019. Paiement has also produced several works for public spaces. Among other distinctions, he received the Prix Louis-Comtois in 2002 and was a finalist for the Scotiabank Photography Award in 2012. He is represented by Galerie Hugues Charbonneau in Montreal. www.alainpaiement.com