[Winter 2020]

By Claudia Polledri

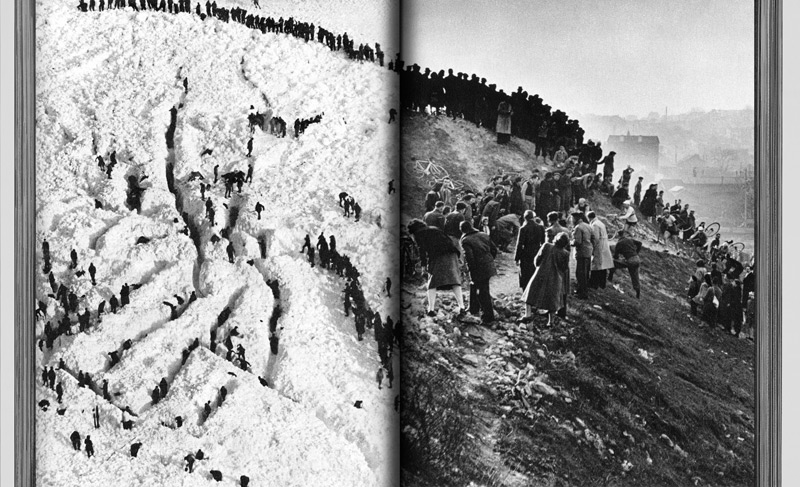

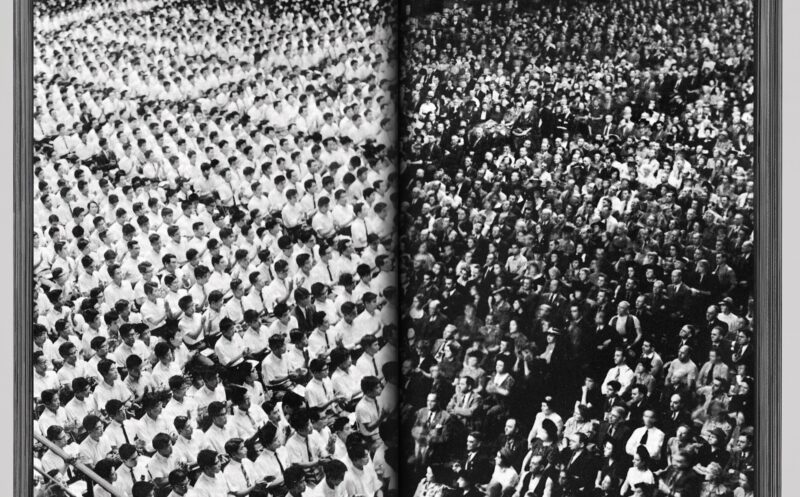

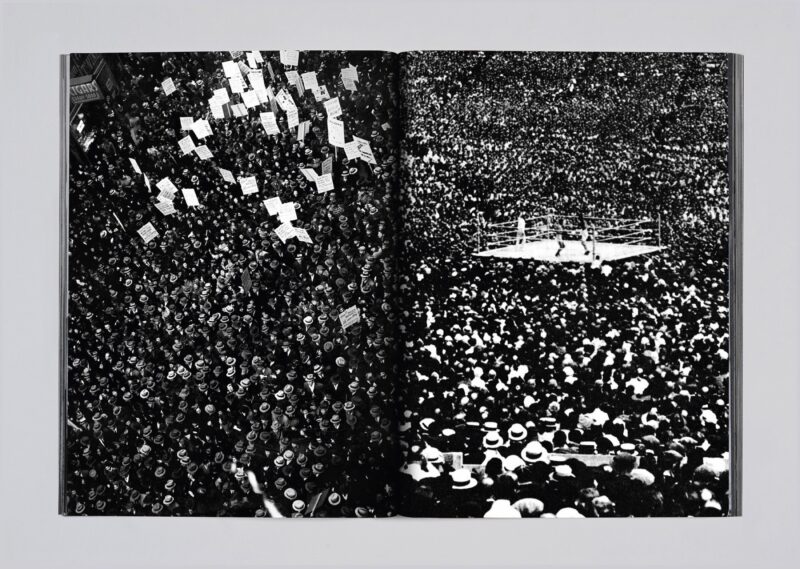

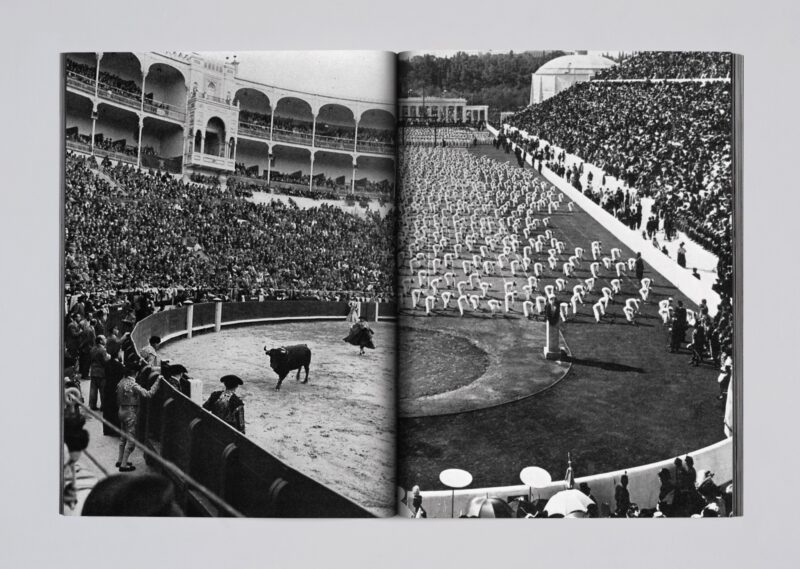

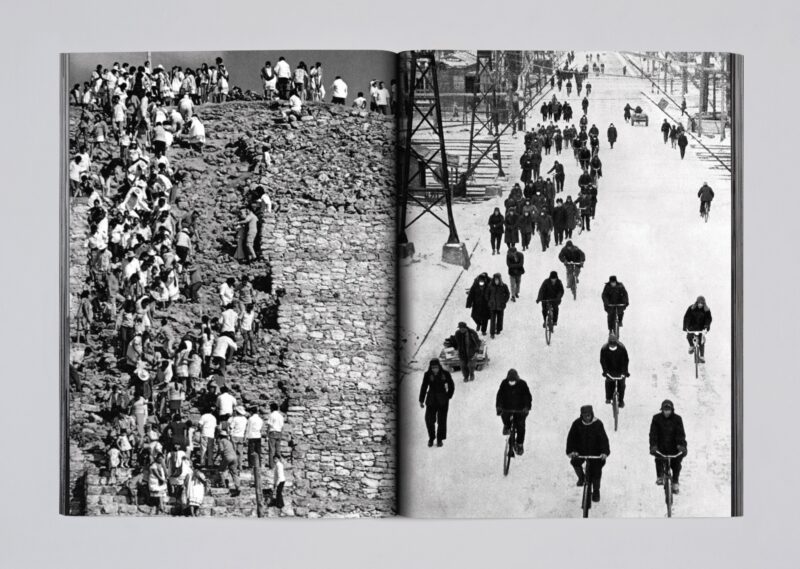

What is a crowd, and how can a photograph teach us about this protagonist of twentieth-century history? In her photobook Foules, Mélissa Pilon underlines the visual complexity of crowds as living organisms, casting an original gaze upon them. In this work, defined as photojournalism, Pilon aims to offer a new approach to the photojournalistic image, as she has arranged more than 130 black-and-white pictures into diptychs. It is an ambitious project – Pilon does not exclude a sequel – bringing together a collection of images from books, magazines, and photographic archives. The timeframe covered is very broad, from 1896 to 2016. Although the list of photographic credits on the back cover contains dates corresponding to the major events of the last century, the photographs are not organized following a chronological sequence. Geographically, there is a wide diversity of countries (almost thirty), and the images were produced by both well-known and unknown photographers. Finally, the total absence of legends describing the context or nature of the event connected to the images – in other words, the reason for these pairings – confirms that any reading of these pictures as illustrations of a historical fact or the present time is here definitively ruled out.

Thus, one of the key principles of photojournalism, the association between text and image, is missing. The frustration is undeniable for any reader accustomed to reading images through the prism of their legends. On page after page, readers are literally assailed by a crowd of questions destined to remain unanswered. What has brought these thousands of people together? Who are they saluting with their arms raised? What are their pickets shouting “no” to? Toward what are they marching or what are they waiting for in the rain? There’s no point in searching, because the only information given about the images (date, location, and photographer) will not tell us. This radical gesture of subtraction nevertheless seems necessary for Pilon to lay the basis for a new structure. In the space left by the absence of legends, she composes a new type of writing through the images, in which the one and only grammar is the representation of crowds. The primary “subject” of this collection of pictures, as well as the true objective of this visual research, thus emerges. Deprived of text – or liberated from the tyranny of the legend, depending on your point of view – the reader/spectator is therefore obliged to look through this collection of photographs focusing only on the shots presented, with a gaze finally free to concentrate on the images.

When we look at these crowds, it is above all the power of their movements, their energy, that seems to come to the fore. Suddenly, we find ourselves searching for clues by following the shapes and trajectories of these human currents, observing how they resemble each other outside of time and space, measuring the tensions and ripples that pass through them. Orderly or chaotic, silent or loud, smiling or anxious, these crowds capture our gaze, which is guided by the play of composition carefully designed by Pilon. Each diptych offers a different association that underlines a particular element in the photograph. Certain combinations emphasize, for example, the relationship between the crowds and space, their free or controlled relationship with the environment or architecture, and accentuate the resulting visual effects. By focusing on the orientation of gazes or the repetition of gestures from page to page, some diptychs highlight the emotional charge that emanates from the crowd. Others play on a “qualitative” description of these assemblies by decoding, sometimes ironically, their psychology via the uniformity of reactions of a collective composed of individuals; and still others are drawn to the quantitative aspect – the immensity of these human tides. We thus grasp the symbolic and political power of such congregations, in which the participants’ profiles converge in a single direction and saturate the visual space. Alongside these associations, some images underline the visual dimension of the subject of “crowd,” illustrating the masses and volumes sculpted by its actions. Others dwell on the pictorial range of crowds, drawing out the geometries created by the arrangement of bodies in the photographic space, the alternation between empty and full spaces, and the play of contrasts between blacks and whites or between clarity and blur. The enlargements shown in the last part of the book, each “section” being implicitly introduced by a blank page, ultimately give shape to the photographic matter and texture of the shots, which become more and more abstract. And then, of course, due to its variety, this collection offers a plethora of anthropological information about different social classes and cultures represented throughout the last century. No longer subjected to the domination of the event, the photographs assembled in this photobook acquire a visual, symbolic, and aesthetic power, producing the significant effect of restoring to the representation of the crowd a new strength and currency that transcends eras.

From this book, the nucleus of Pilon’s photographic and aesthetic research, resulted an eponymous exhibition presented this summer at the tenth edition of the Rencontres internationales de la photographie en Gaspésie. Placed in a setting that was both suggestive and historically charged, where massive land expropriation in the 1970s preceded the creation of Forillon National Park, Foules follows essentially the same diptych structure as the book. The landscape was spectacular: on one side, the horizon opened out to the river in the distance; on the other side was the protective flank of the mountain. In the middle, on raised ground, Pilon’s images were printed on both sides of rectangular panels rising vertically from the earth and somewhat separated from each other. It was up to spectators to assemble the diptychs as they wandered through the space. Only one image placed on the ground, portraying an audience of children, their faces attentive and surprised, was set apart from the rest of the exhibition path. It was a sort of inaugural image that metaphorically projected these photographic readings of the past into the future. Of course, as is often the case, the exhibition generated a quicker experience of the images than does the book, as the details and the structure as a whole do not appear with the same precision. Here, however, the site itself produces the secondary, beneficial effect of endowing the visual and symbolic presence of crowds with even greater strength. Reflecting the history that has marked this land, though not limited to that reflection, Mélissa Pilon’s generous, refined photographs took on a new form of realization and reactivation of memory in this exhibition, bringing her artistic approach to life and making it even more embodied.

Translated by Käthe Roth

A postdoctoral student and lecturer in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Université de Montréal, Claudia Polledri is also the academic coordinator of CRIalt (Centre de recher ches intermédiales sur les arts, les lettres et les techniques, UdeM). She holds a PhD in comparative literature from the Université de Montréal; the subject of her dissertation was photographic representations of Beirut (1982–2011) and the relationship between photography and history.

Mélissa Pilon is a visual artist and graphic designer with a degree in photojournalism and image culture from the Werkplaats Typografie in the Netherlands. Through poetic narrative, photographic essays, and exploration of archives, Pilon deploys a practice of visual writing. She has contributed to numerous projects, including Paul Ellman’s Untitled (September Magazine), and participated in many international group exhibitions. Her project Fox News, produced using a portable digitizer as camera, was published in the form of a journal by Werkplaats Typografie in 2014, and a solo exhibition in Montreal followed. Among the grants she has received is the Bourse d’excellence du millénaire from the Faculty of Arts at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She lives and works in Montreal. www.melissapilon.com