[Summer 2021]

Bertrand Carrière, Learning photography from books

An Interview by Serge Allaire

Over the last forty years, Bertrand Carrière has produced a personal and varied body of photographic work. His photographs have been exhibited in Quebec, Canada, Europe, and China, and he is represented by Galerie Simon Blain Montreal and the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto. He has taught photography at the Université de Sherbrooke and received grants from arts councils in Canada, Quebec, and Longueuil. He has published several books, including Le Capteur (éditions du Renard, 2015). In 2020, a retrospective exhibition and monograph, both titled Solstice, highlighted the breadth and depth of his practice.

SA: I’d like to talk about your overall approach and the process that led to the Solstice exhibition and book. How did you get the idea for this retrospective project?

BC: I was thinking about a book that would bring together several of my projects. For various reasons, I was sometimes dissatisfied with the previous books: choice of images, layout, printing quality. I wanted to make up for these shortcomings with a book that would be a collection of short excerpts from my projects and previously unseen images. The idea for a retrospective exhibition was quickly abandoned in favour of a collaboration with Plein sud éditions for a monograph.

Then, I received an invitation from Galerie d’art Antoine-Sirois at the Université de Sherbrooke, holding out the possibility of producing a retrospective exhibition. I had already started putting together the book, and I decided to work on both in parallel. After that, the university gallery offered to co-publish the monograph, which involved a major financial contribution.

For the exhibition, which is very different from the monograph, I chose to work with available prints and devote one project to each wall of the gallery. I wanted the exhibition to breathe. I used only images produced starting in 1996. I was my own curator; I selected the works and hung them. I was helped by a really good team at the gallery, starting with its new director, Caroline Loncol-Daigenault, and Mona Hakim helped with the texts.

SA: And the monograph?

BC: Thinking about and working on the monograph started a year before the invitation for the exhibition. This was related to a major reorganization of my studio and a huge research and digitization project. That’s how I came to look over images from the twenty early years, which take up the first half of the book.

During the year, I took advantage of access to the Quebec studio in London. Of course, that six-month stay delayed both projects, but it gave me room to step back and take a fresh look at them. I left for London with a preliminary mock-up of the book, and I had a lot of time to think about it. What luck! I think that the distance created a better book and a better exhibition.

SA: You’ve published a number of photobooks. How important are books to you? How did you discover this form of dissemination?

BC: I really learned about photography through magazines and the LIFE encyclopedia. And the discovery of books was fundamental. The first one I had was a short monograph on Henri Cartier-Bresson, published by Delpire. As broke as I was at the time, I had to borrow it for a very long time. Then, Diane Arbus’s book and Josef Koudelka’s Les Gitans bowled me over.

Finding Charles Harbutt’s Travelog was significant to me for his very personal vision. I was thrilled by his intimate approach to the travel diary. Then, Garry Winogrand’s Public Relations was a turning point because of his anti-journalistic approach, the use of the flash, and what was called snapshot aesthetics.

I learned photography from books. It’s the most appropriate form for deployment of my projects. It always has been. My first major project – Les amuseurs publics (1979–81) – became a book mock-up for a competition organized by the magazine OVO. I was already working on the sequence of images, but clumsily. My tools were very primitive.

SA: Can we see a connection with film editing in the conception of a book – in the choice and assembly of images?

BC: Many of my projects start with a fairly vague idea. Sometimes, the images arrange themselves into series. Yet, even when it comes to more documentary projects, the true creative work happens when it’s time to organize the images sequentially, by juxtaposing them. It’s true that this bears many similarities with the process in film, where editing has the final say. I always liked the idea of going in search of images, without a precise script: to create on a table, with small proof prints, in order to discover the meaning in them, buried in the encounter with the images. It always ends up resembling a book. I have a cupboard full of mock-ups.

All the images in Solstice were first printed in small format, then spread out to form groups and sequences. Only after that did the on-screen work begin. There is something important in the materialization of images, like a deck of cards, necessary for the selection process.

This process, this automatic writing with the images, in which meanings bump up against each other and clash, satisfies my search for meaning. But there’s no simple formula or easy method for reaching a meaningful grouping. It’s a procedure that’s quite intuitive, that you have to go through each time. It’s probably the most difficult part of any photographic undertaking: choosing, perpetually choosing, and challenging your choices.

One creates by subtracting. If I’ve learned one thing with the editor of my films and that I try really hard to apply, it’s how to see the tree (the image) and the forest (the book, the film) at the same time: the unique importance of each image, each shot, in a whole that makes sense.

SA: In this process that led you to review your projects since the 1970s, did you discover, or rediscover, photographs that you had neglected and that seem more significant now?

BC: That was one of the most exciting aspects of creating this monograph: reviewing old work with today’s eyes. Because my point of view has changed, the contact prints and prints offered a wealth of new directions.

The work with Hélène Poirier, of Plein sud, was particularly pleasant. She made numerous suggestions on which works to integrate in order to break up the chronological linearity. She increased the number of pages to facilitate integration of new works and saw to the unity of the book as a whole.

I chose to publish a good number of images that had never been seen, some of them from projects never shown, such as those taken from the North Shore and from Scotland (Don’t go to Glasgow, 2018), and the most recent, Miroirs acoustiques, produced in England. Each series is in small format; some take up more space than others. Sometimes they are emotional choices, related to the importance that I wanted to grant them. The book contains some thirty projects.

SA: I was struck when I first read the book by the absence of titles and by the notes that distinguished each part or project. Can you talk about that?

BC: In my books, I’ve almost always avoided placing titles under the images. I find them distracting. In Solstice, there are notes on the titles and the years of the series, but all the other details are at the end. What I wanted to make visible at the start became more discreet as the design evolved. I privileged a more harmonious transition among series, genres, and eras. I wanted to give precedence to the sequence of the images, to create a continuous flow and minimize graphic interruptions between the series. I wanted to avoid a “catalogue” effect.

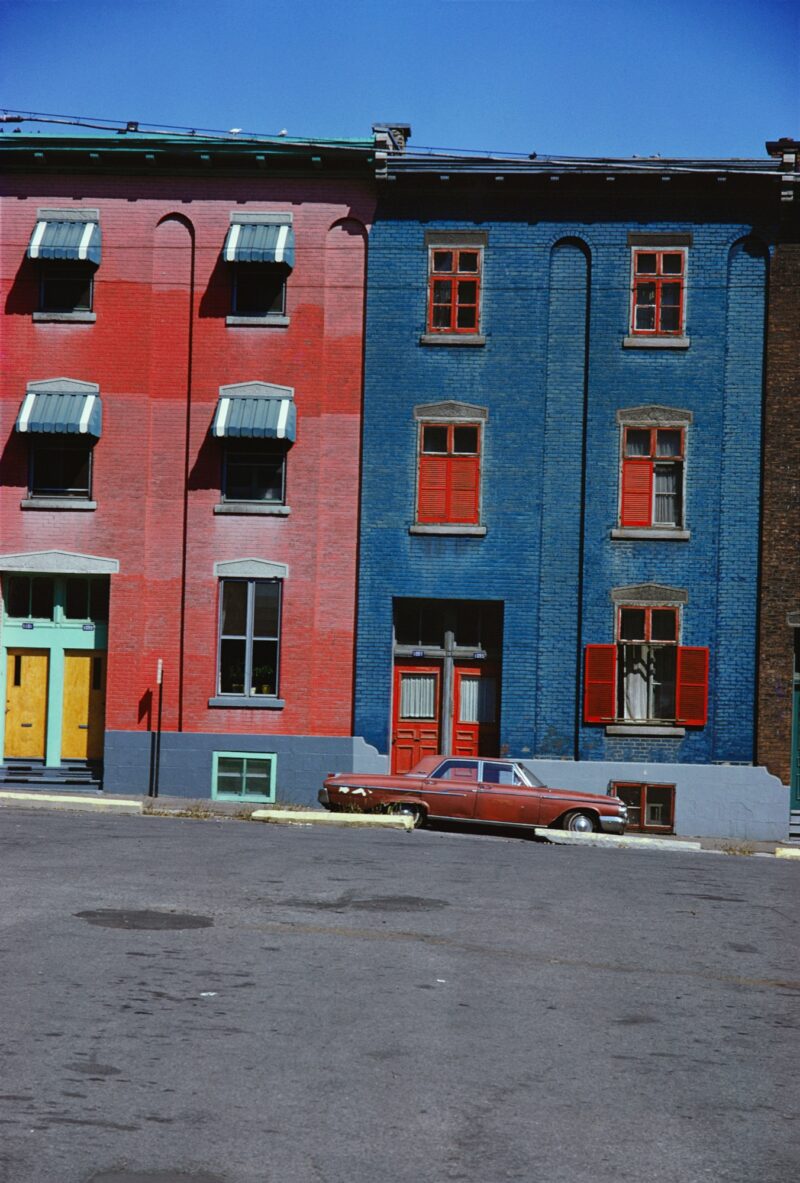

SA: In general, the first images in a book give the tone to the book as a whole. Why did you choose to start with colour images?

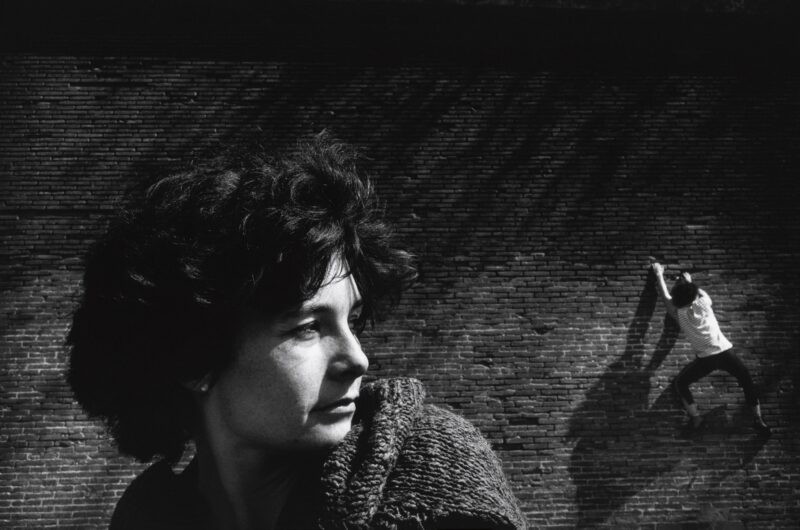

BC: The very first image in the book was a chance find, an image that I probably made when I was fourteen or fifteen. It’s of a part of Montreal that no longer exists. What touched me is that it resembles what I can do today, like the series Le Capteur, which closes the book. The second image was made during a trip to Paris in 1981. Another chance find. In both cases, I realized that there is a part of my gaze that hasn’t changed – I still love these images. And considering the conditions under which they were kept, it’s a small miracle that they survived. When I saw them, I knew that they would open the book, offering at once a look at the past, an enigma, and a sort of revelation. It’s a true privilege to be able to go so far back in my work and still find relevance, and resonance, with what I’m doing today. Translated by Käthe Roth

Serge Allaire has taught in the department of art history at UQAM. An independent curator and history of photography researcher, he has contributed to Mois de la Photo à Montréal as an author and written for many photography magazines. More recently, he has devoted himself to bringing Quebec photobooks to prominence in Canada and France.

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]