[November 29, 2023]

By Louis Perreault

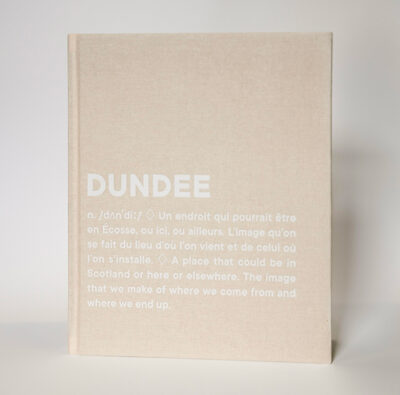

The cover of Hua Jin’s book Dundee immediately reveals the ambiguity of what is contained within. A simple made-up definition of the title word, printed in white on the cream-coloured cloth, hints at the poetry infusing the book’s pages: “A place that could be in Scotland or here or elsewhere. The image that we make of where we come from and where we end up.” Thus, a village in the Haut-Saint-Laurent region, called Dundee by its first habitants – who had come from a town of the same name in Scotland – offers a pretext for reflecting on the desire for permanence that surfaces when migratory movements force cultures to relocate.

Hua Jin, Dundee, Québec City, éditions VU, 2023, 148 pages, hardcover, sewn binding, 23 x 28 cm, bilingual.

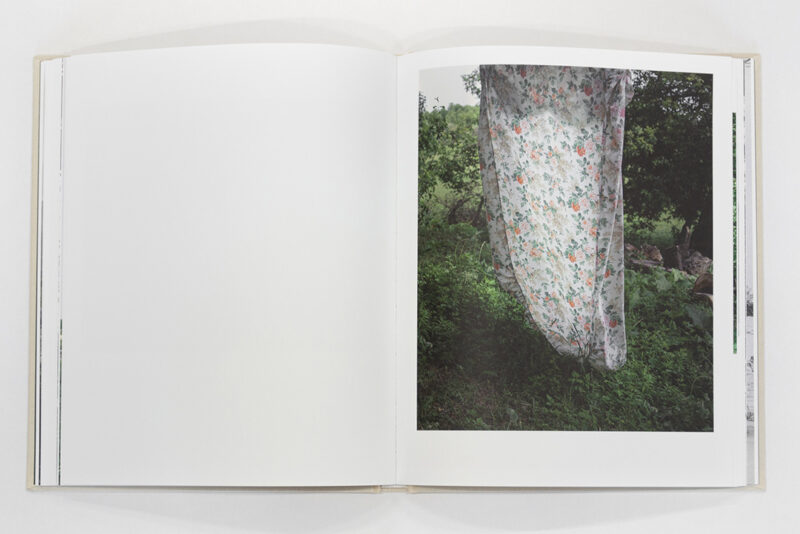

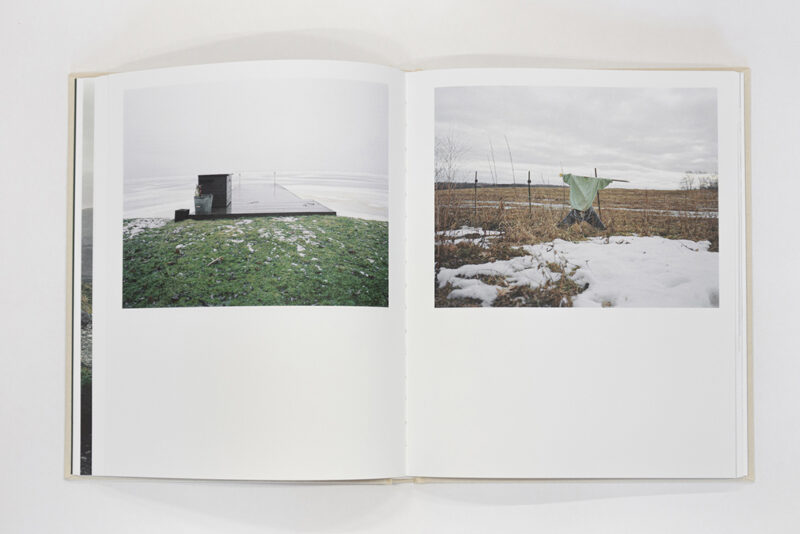

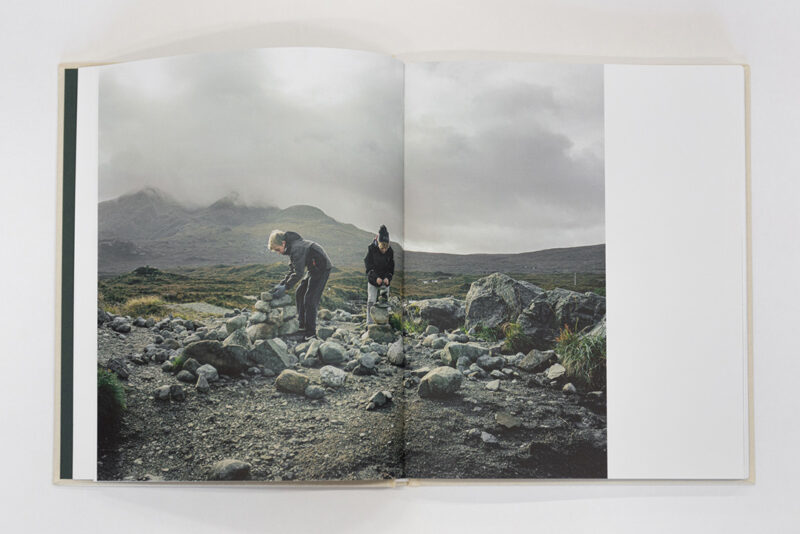

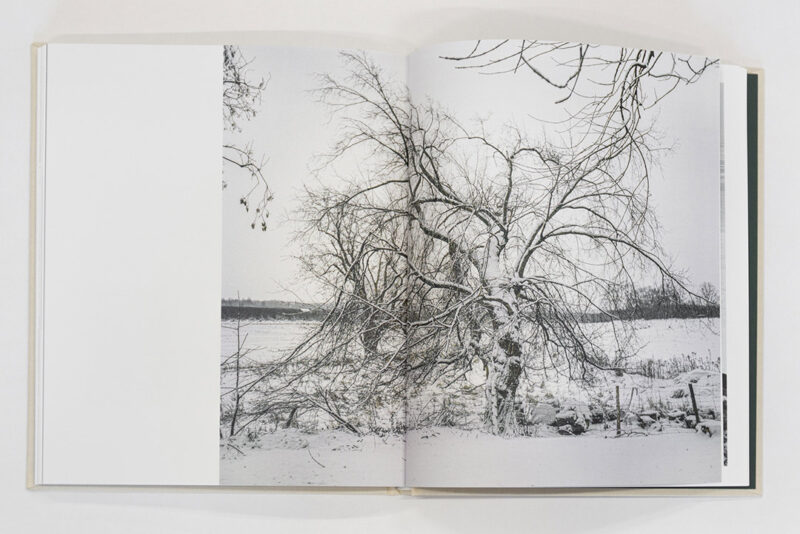

As a consequence, even though the book’s title seems to indicate that we will find a localized and specific work, Jin has chosen not to name, either in the text or in the list of works, the places that she has photographed. We will probably recognize the Quebec landscape, and we may suspect that the great stretch of water and ice that opens and closes the series is the St. Lawrence River, but, despite these familiar-seeming visual references, there’s the persistent feeling that these undefined spaces could be “here or elsewhere.” This impression is reinforced by the apparently random insertion of images showing verdant, sometimes foggy Scottish hills that could be memories of places visited in the past.

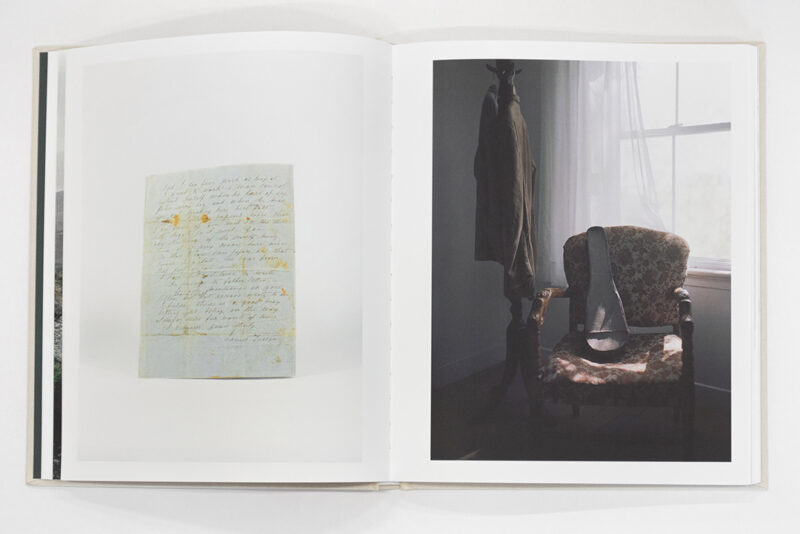

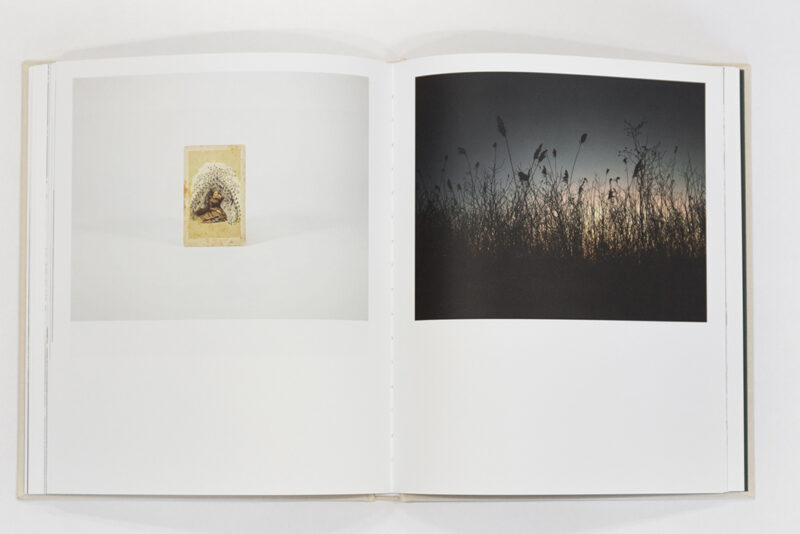

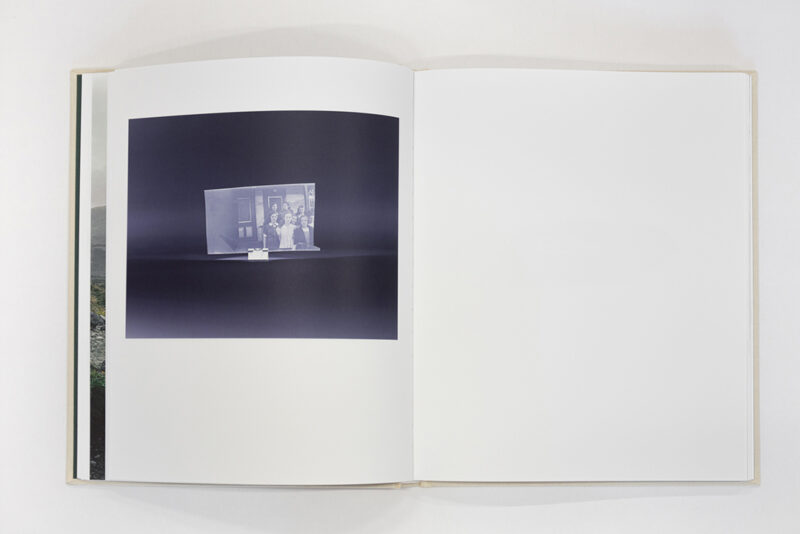

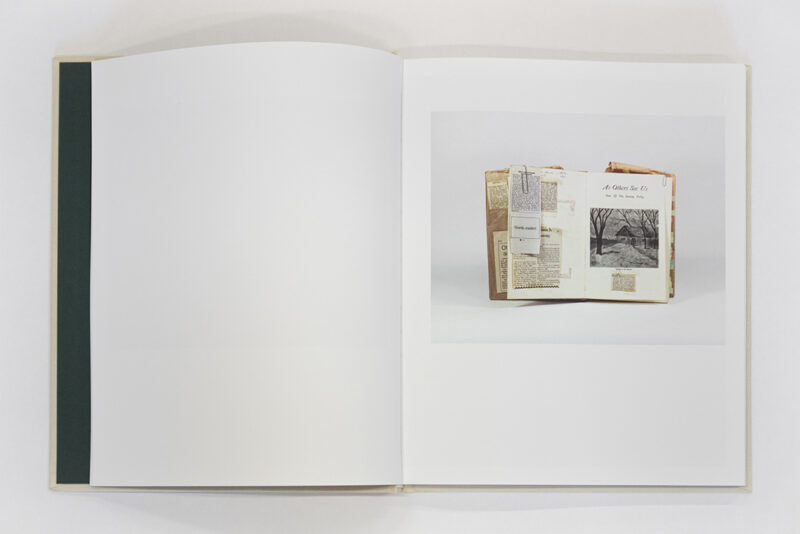

Also punctuating, and complexifying, the sequence are archival objects photographed against a white background in the studio, which add a temporal dimension to these geographic movements. What are these worn old books, bearing barely legible handwritten inscriptions? Who are these women on the negative held by a paper clip? Whom do all these artefacts from an ancient past belong to? Jin makes no mention of them, and we have to use our imagination to create a narrative connecting these sparse, dispersed points.

Given that this work is based, after all, on a basically documentary exercise, might the inclusion of a few bits of text have made it a bit more engaging? Because we will inevitably want to know about both Dundee in Quebec and its Scottish counterpart – our curiosity being piqued – we will have no choice but to put the book down in order to find the missing details in order to understand the work.

Yet what might seem opaque is also what is attractive about the book: by not revealing everything, Jin provokes a sense of disorientation that evokes how uprooted migrants must feel. In the new landscape of a host country, might they not try to decipher clues to a world they don’t know, try to make sense of everything by infusing it with their own reference points? Herself an immigrant, Jin seems to have found in the example of Dundee a reflection of her own history. This place and its history bear witness to the undeniable importance of cultural intermixing, caused by migratory waves, to the foundation of the towns and villages that we live in.

Finally, we appropriate Dundee as we embrace a winter landscape, whose space we feel through the cold wind blowing in our face. Similarly, in this book, we experience the weight of time in the carefully observed stone foundations photographed in Scotland, in the yellowed, wrinkled paper of an archival note, or in the immediacy of a rosebush in bloom. Instinct and intuition carry us as if these objects and places had belonged to us in one or another moment in our past. And so, it becomes difficult to blame Jin for not telling us enough: we are all part of the great movements and displacements that have marked and will continue to mark history. Translated by Käthe Roth

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.