[Summer 2024]

by Hélène Samson

[EXCERPT]

The current photography collection at the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) was built from various sources. The original international collection was established by curator James Borcoman in 1967. After the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP) closed, in 2009, the NGC incorporated its collection, which included the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board of Canada. Andrea Kunard, known for having curated exhibitions at the NGC such Fred Herzog (2011), Michel Campeau: Icons of Obsolescence (2013), Photography in Canada 1960–2000 (2017), Moyra Davey: The Faithful (2020), and, most recently, Kan Azuma: A Matter of Place (2024), is now in charge of the Gallery’s large collection; in 2021, she was appointed Senior Curator of Photographs. Here, she discusses her main challenges and objectives.

hélène samson: You have been at the National Gallery of Canada’s Photography Department since 2009, and you were appointed Senior Curator of Photographs in 2021, succeeding Ann Thomas. My first question is a broad one: how do you see your mandate inside the institution?

andrea kunard: The institution has its own mandate and is affected by changes both within and without. In this context, I see myself in a position of caring both for people and for the collection. There are different histories of photography in the institution. They are very interesting, and they need to be preserved. I started as an assistant curator at the CMCP. That important collection had its roots in the National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division (SPD), which had its own history. The SPD’s executive director, Lorraine Monk, worked very hard to produce a Canadian photography collection when nobody else was really interested. This work was continued by Martha Langford, Martha Hanna, and Pierre Dessureault at the CMCP when it was established in 1992. At the National Gallery, Jim Borcoman was very invested in creating an international photography collection, and Ann Thomas continued that kind of work, assisted by Lori Pauli. So, many people have been involved in putting together these collections, and I feel incredibly honoured to be able to continue and preserve that work.

It’s important to understand that photography is not one thing; it’s many things. In my own research, I always think of photography as something living. It’s something that engages people on a daily basis – think of social media, for instance. Individually, people have photographs, exchange them, talk about them. When they come into the National Gallery and see framed photographs on the wall, they like to bring in their own views, their own experience of the world.

I also think it’s extremely important to have various ideas of photography in the same institution to have on display constantly: from different cultures, different countries, different understandings of photography. The current exhibition, Kan Azuma: A Matter of Place, revisits the collection to show a style of Japanese photography that developed because of that country’s culture and history. Azuma then used that aesthetic to interpret his experiences of Canada in the 1970s. I want to develop that kind of diversity. I am interested in Asian photography, and also in African photography. I want people’s stories to be told by them through photography.

hs: What happened with the David Thomson Collection, acquired in 2015, and with creating the Canadian Photography Institute (CPI)?

ak: The Thomson Collection, which comprises mainly early American photographs and equipment, such as a large quantity of daguerreotypes, is part of the main collection. The CPI does not exist anymore. So many things have changed at the institution. People have left.

hs: How would you describe the process of acquisition for the photography collection?

ak: I’m responsible for the continuity of those collections. I make acquisitions through donations and purchases. I work with recognized art dealers. The acquisitions committee meets six times a year. I buy what is best for the National Gallery.

hs: What’s the main principle in the acquisition policy for photography? What are you looking for?

ak: Recently I bought a Diane Arbus, three Nan Goldins, and three Peter Hujars. Strangely enough, Goldin and Hujar were missing from the collection.

Of course, there are numerous missing parts in the collection – for instance, Canadian Pictorialism. This aesthetic movement was especially dominant at the turn of the twentieth century, when photographs were composed according to painting subjects and principles; there’s not enough representation by Canadian artists in the collection. In a current exhibition, I’ve included a few Pictorialist artists: William Gordon Shields, Minna Keene, and Sidney Carter. I would like to have more.

hs: Are you advancing as much in the Canadian field as much as in the international field?

ak: I feel a strong responsibility toward Canadian photographers. That is a tough issue, because many of them are getting older and they want to donate their archives, and we don’t have enough room. That is very hard.

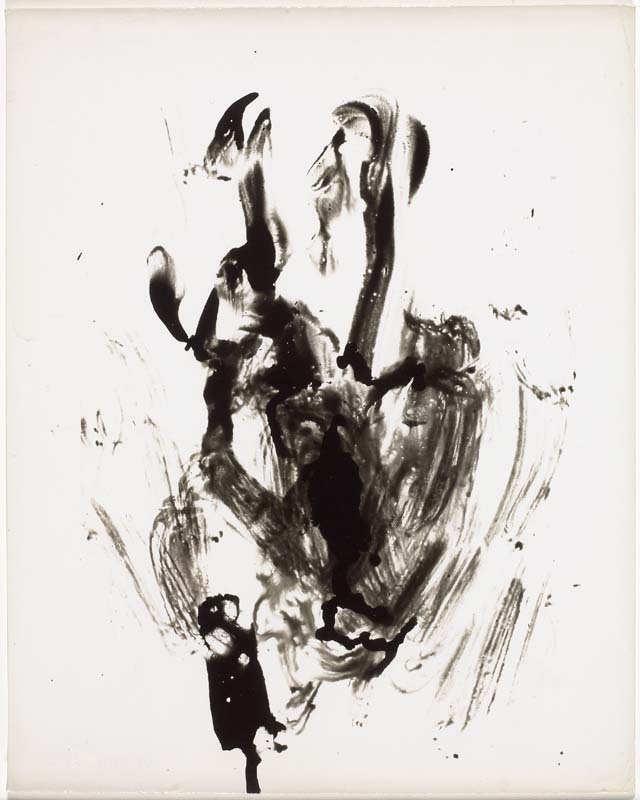

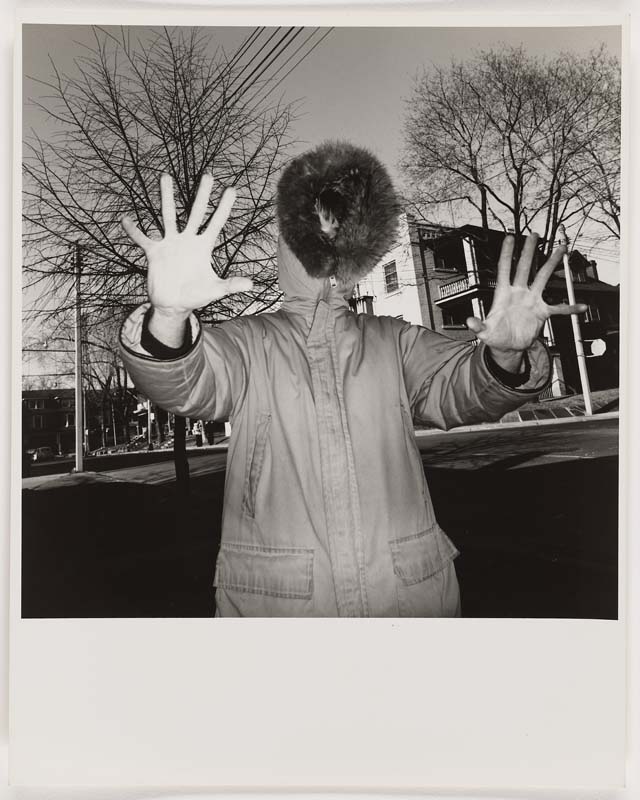

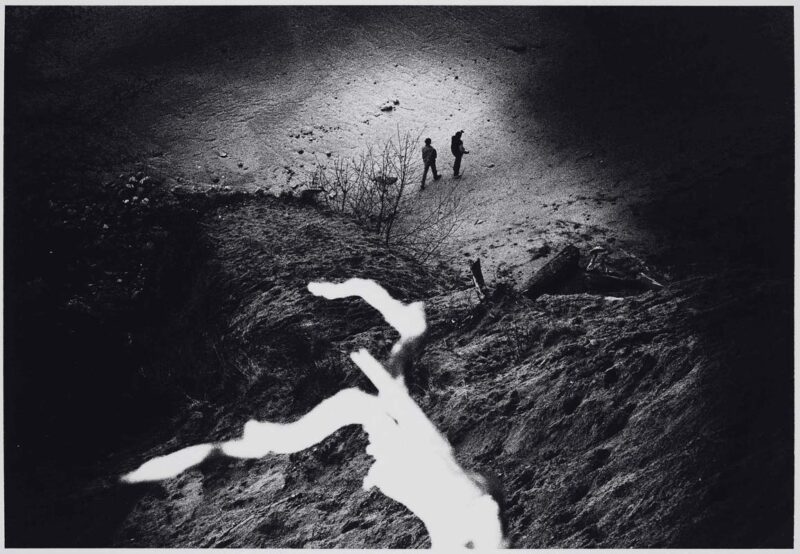

I am sensitive to the fact that there are different kinds of histories in different areas of the country. Quebec has its own. Very interesting things are happening in the North, in Nunavut. There is a lot to do. I do try to balance things – it’s important to a national institution. Right now, I have a strong research interest in what happened in Quebec during the 1950s. It seems quite unusual. Artists such as Guy Borremans and Jauran were exploring visual abstraction and experimenting with photographic material. They were influenced by avant-garde artists such as Moholy-Nagy through Gordon Webber and the New Bauhaus of Chicago.

hs: Do you promote Canadian photographers at the international level?

ak: Well, I write a lot, but nothing yet is planned in terms of touring exhibitions or anything like that.

hs: You have so many stunning exhibitions to your credit – Photography in Canada 1960–2000, accompanied by an outstanding publication, to mention just one. Who plans the photography exhibitions?

ak: Me. Just me. But there is a programming committee I present my ideas to.

hs: How many people work with you in the Photography Department?

ak: Only one full time at this point! My assistant curator, Euijung McGillis. But I work with colleagues across other departments, and an assistant curator, Jasmine Inglis, is cross-appointed to Photography and Contemporary Art.

I am working in collaboration with Library and Archives Canada in a program called Focus. They have a huge collection of Canadian historical photographs, which complement ours. For the Focus series, I curate a small group of photographs, prints, and other objects for installation in the Indigenous and Canadian Art Gallery, where almost eight hundred paintings, sculptures, prints, photographs, silver pieces, and decorative art objects from across Canada, dating from five thousand years ago to 1967, are on view. Each series has a theme related to works of art shown in the gallery. For example, there is a series on the sleigh dog in Canadian and Inuit culture, one on Inuit women’s tattoos, one on labour issues during the Depression, and so on. I am also interested in mixing historical and contemporary photographs with other forms of art.

hs: Does one exhibition stick in your mind more than others?

ak: (Pauses) Moyra Davey! It was at Concordia University [Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery], during COVID. It was also shown at the National Gallery for a few weeks before everything shut down. Hardly anyone saw it in Ottawa. It’s sad. Moyra has a really interesting idea about using photography as a touchstone for memory and language. She integrates literature, histories, and politics in her work, building a kind of constellation around her projects. I like her idea that images, objects, and language – and even herself as an artist – are always in process, as are the viewers looking at her work.

hs: How do you preserve photographs in the collections, considering the proliferation of digital media?

ak: We still buy the actual artwork. I am starting to buy digital. It helps for storage, but there are other problems coming along. We have a conservation department with conservators who specialize in photographs.

I am very interested in colour shifting – early colour photographs whose colours have started to change. This is a problem when you want to show the works, especially when the artist is still alive. This issue must be addressed as characteristics of the process in the long term.

hs: How do you see the future of photography? Following the shift from analog to digital photographs, what do you expect from the arrival of artificial intelligence (AI)?

ak: I find AI very interesting. It’s something I want to look at more closely. I am curious to see how we are going to interact with this technology. Given that photography is technology, it is part of the way of thinking that has led us to AI. I’m not judgmental about it. I am interested in the biases: how algorithms are not neutral but full of prejudices; also, how different groups of people are using AI. Just as they have always used photographs.

—

Hélène Samson (PhD Université de Montréal, 2006) retired in 2022 from the McCord Stewart Museum, where she was appointed Curator of Photography in 2006. She was responsible for developing and disseminating the photography collection. She has curated numerous photography exhibitions, notably Notman: A Visionary Photographer (2017), Alexander Henderson – Art and Nature (2022), and several shows of contemporary Quebec photographers. She has published books on Notman and Henderson and numerous articles in national and international magazines. During her mandate, photographic culture gained major importance in the institution. She is currently working as an independent curator and associate researcher at the McCord Stewart Museum.

—

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 126 – TRAJECTORIES ]