[Fall 2024]

The Atlas: A Word

by Edward Pérez-González

[EXCERPT]

Standing against the imperatives of an era marked by accelerated time, dismantling of concepts, systematic interdiction of doubt, and the attention economy, the exhibition Atlas, nébuleuses du Sphinx1 invited us to slow down, to take a break. With its easy simplicity, far from the immersive digital installations and scenographic gimmicks in style these days, it allowed for reflection. It asked us not only to hone our gaze but, above all, to stir up our perceptions, to see the invisible, to be there without a body.

At first glance, the exhibition was an atlas – a collection of images and maps and explanatory documents. In fact, it was an extensive and profound mapping of events,2 a force field3 as backdrop for the production of singularities. Multiple and heterogeneous meanings emerged and intersected. Here was an invisible field of invisible lines; a stage for complementary or competing vectors that created and broke alliances, that became memories of what is experienced and imagined.

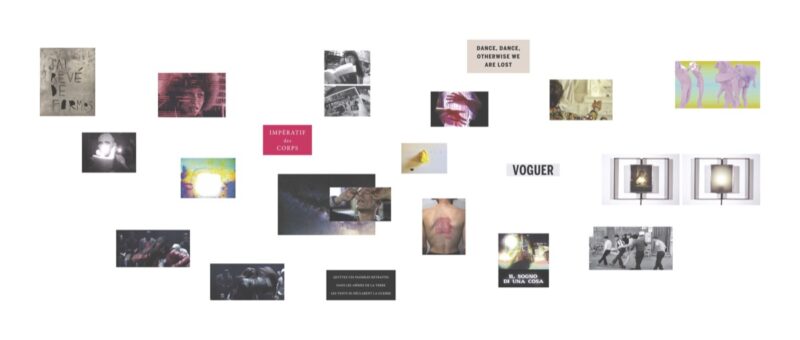

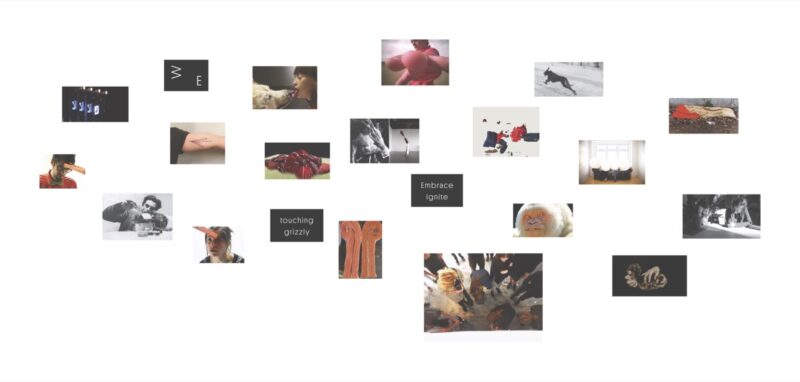

Existential enigmas. In the first gallery, the nebula Questions adressées au Sphinx: l’épreuve, le désir, l’étonnement (Questions for the Sphinx: The test, the desire, the astonishment) brought together twenty images and texts that gave the exhibition an exploratory feeling. Vachon played with the scales of time and space through twisting, coupling, or opposition. She was aware of her limits and of the challenge she was taking on. She warned us that the exhibition was filled with enigmas, such as great existential questions about us and the universe. She drew on Alberto Giacometti to structure her inquiry: “Our activity is but a continual question to the universe, which is also us. For each of us, the world is in fact a sphinx before which we stand continually, a sphinx that stands continually before us and that we question.”5

Among the texts presented was an excerpt from Jorge Luis Borges’s L’autre, le Même: “How can the simple chronicle of images communicate the astonishment, the exaltation, the startling, the threat, the euphoria that wove that night’s dream?” Vachon accepts the impossibility of accessing comprehension and the difficulty of fully transmitting the experience through this universe.

An arm in flames. Hands covering the lit-up eyes of an anonymous face, others placed on the sides of Pina Bausch’s cheeks. The bust of a classical-era athlete and one of a Navajo man from the early twentieth century. Timeless heads, some faceless. All of these images were part of a living dialogue. Cosmic landscapes, people, and butterflies intermingled with a photograph from the monograph Beside myself/Hors de moi by Daniel Olson, who had a video presented in an adjoining gallery. Semantic constructions were constantly emerging, such as that between a paragraph inspired by Zeno in Marguerite Yourcenar’s L’œuvre au noir – “I am one, but multitudes are within me. Borne by astonishment. Allow me the possibility of losing myself” – and an excerpt from Marie de Quatrebarbes’s performance work Pourquoi hanter les maisons, y vivre ensuite.

This section included Maude Bertrand’s video collage Les braises (2023), the silent vestige of a vocal performance produced for the exhibition. It also contained Florence Viau’s sculpture Ce que gardent les pierres (2021), which, inscribed between materiality and immateriality, explores the tensions between old and contemporary media. Inspired by the Rosetta Stone, Viau challenges archetypes for preservation of communications and memory. Her monolith, a hybrid object, embodies both the lastingness of sculptural forms and the fragility of printed and digital images.

A listening device for a work by the musician and composer Isaiah Ceccarelli, Toute clarté m’est obscure (2021), occupied a small alcove. The piece suggests that truth resides in the nuances. Organic and elegant, these harmonic clouds, the title of which is borrowed from an anonymous fourteenth-century ballad, offer an introspective look at human life. In this deep resonance, language becomes the very fabric of creative thought, and we are invited to embrace the complexity of a soundtrack in which sung words, scriptural interludes, and improvisational moments intersect. At the back of the room, a magnetic tape was projected on a screen. Forming a seemingly infinite river, the tape’s meanders become almost a tool for meditation. Without knowing it, we were contemplating a live idealized representation, activated by a mysterious machine revealed later in the exhibition. Intensifying the sensory experience, the space was filled with the sound, from an unknown source, of a piece of paper being crumpled.

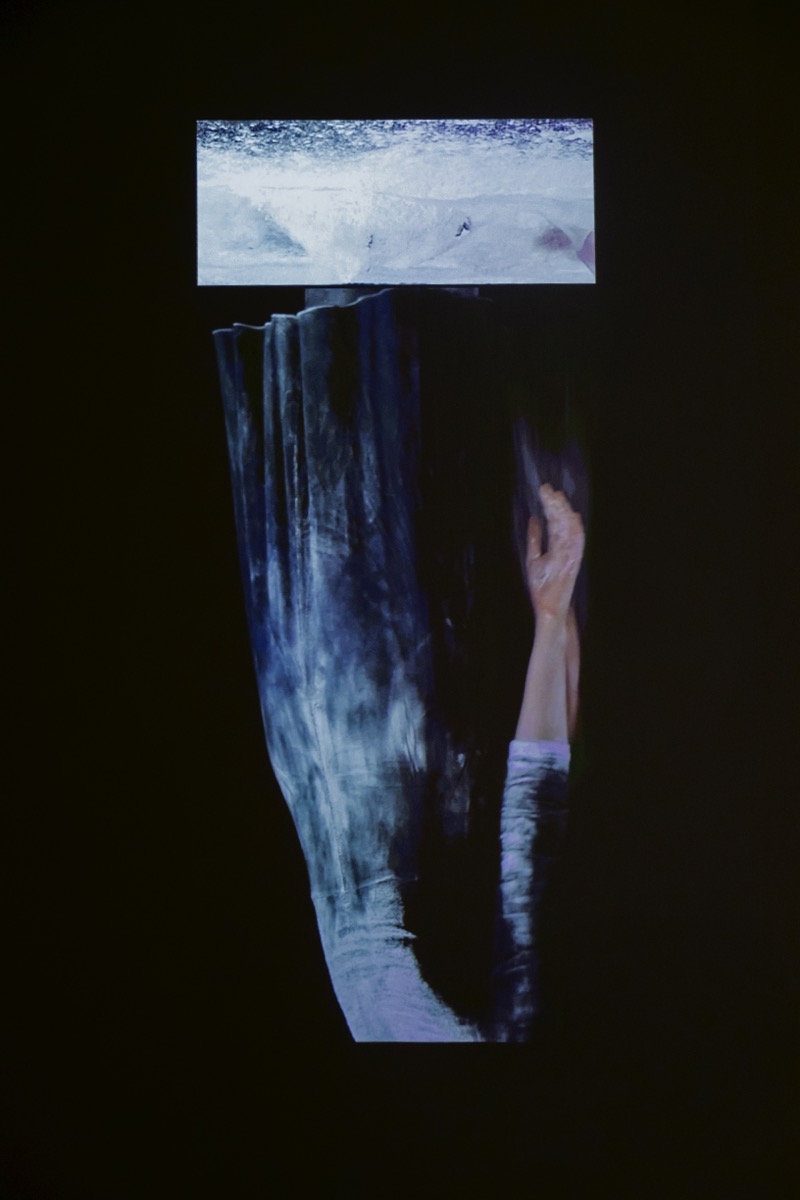

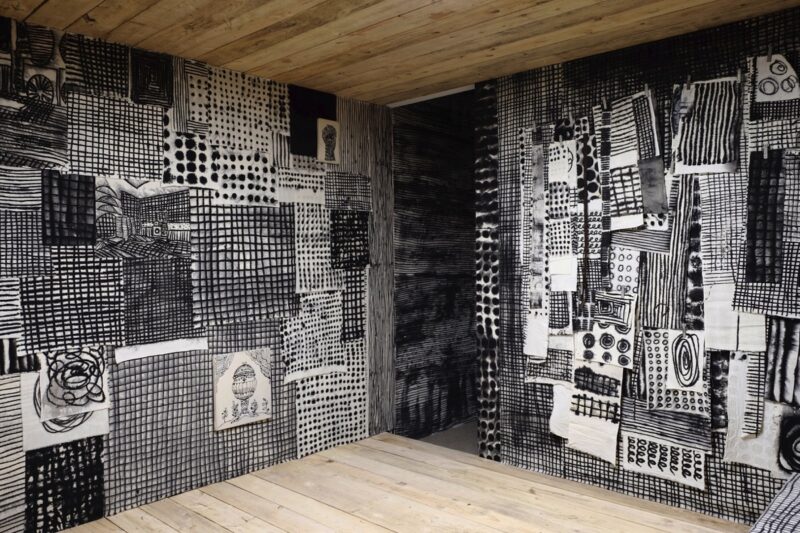

Visual topography. The four other nebulae shared a large gallery whose path began with Jacynthe Carrier’s Aux alentours (2023), a reflection on the ephemeral nature of encounters in the flow of life. In this video, as in the meeting and intermingling of the saltwater of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the freshwater of the St. Lawrence River, moments captured on different shores combine in a moving dialogue. Marie-Claude Bouthillier’s installation Dans le ventre de la baleine (2010–15), a delicate fusion of the tactile and the optical, rose as a refuge. In this enveloping compartment, Bouthillier weaves a complex canvas of reality and imagination. Halfway between painting and drawing, a Virgin Mary is set in opposition to a figure who seems straight out of a deck of cards. This pictorial world is deployed in a small room with transcendent sensory dimensions. As it grazes the space, this “line machine” creates textures and triggers a kinetic interplay that is echoed throughout the exhibition.

There were so many images and references presented in each section that it would be impossible to describe – or even name – them all. Surprisingly, Vachon was able to unify an operative topography of visual and conceptual through-lines. The Incantations nebula spoke of dance as a bodily imperative in which corporeal, political, poetic, and private facets overlap to build resistance. Vachon herself was in evidence from one end of the exhibition to the other, not only through the conceptual scaffolding that she had articulated but also through her own pieces. She reconceived a work by Frédérique Beaupré-Decoste in Archive Tournesols (2021), using elements from one of the latter’s previous installations, Hélianthes annuels ou fleurs de soleil (2020), which was presented at the other end of the gallery.

Away from the nebulae and arranged in islets in the centre of the space were volumetric works of various materialities and styles, including a figurative sculpture by Vincent Lussier portraying Atlas as a child and a kinetic geometric sculpture by Mélanie Dumas, Capturer l’insaisissable (2022), which functioned, despite its static position, as a reverberation mechanism. François Rioux’s Peaux (2023–24) bringing together two textile elements – a cape reproducing the camouflage motif of Cryphia muralis and an embroidery of the moth’s wings – speaks unequivocally about metamorphosis. The work evokes a dynamic of separation, self-protectiveness, and adaptation.

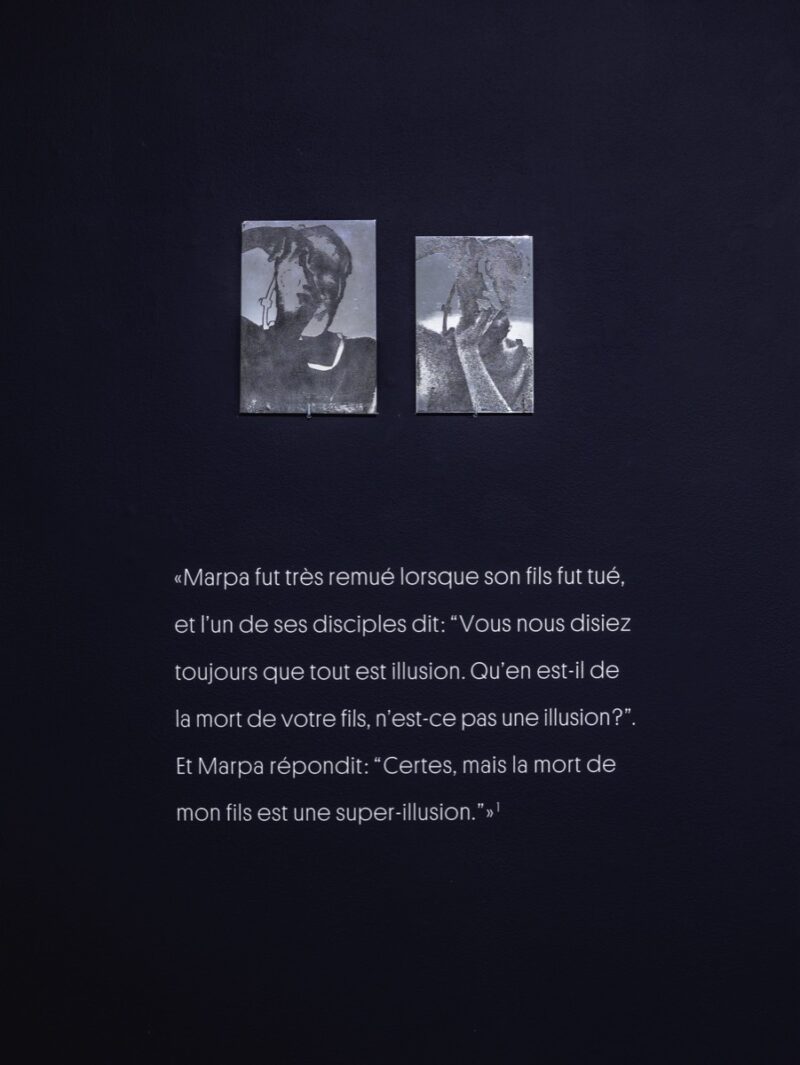

The Nous (We) nebula explored the duo of Embrasser Embraser through a “reflection on our relationship with the other and with difference, with fragility, and with the mysteries that connect us.” The following nebula, Archives des ténèbres, épreuve de la lumière, (Archives of darkness, test of light) “probe[d] multiple memories linked to documents, archives, and obscure image and sound supports.” Finally, the Amor Mundi, quand nos yeux se touchent (Amor Mundi, when our eyes touch) nebula took its title from a book by Hannah Arendt, Love and St. Augustine, and the chapter “When Our Eyes Touch” from Jacques Derrida’s On Touching – Jean-Luc Nancy. Masterfully interweaving heterogeneous elements, Vachon put these ideas on a collision course, taking from Arendt the idea of love of the reality of the world and for the human condition, and from Derrida the notion of a relationship between touch and visual perception. A pair of photo-engravings made by Alex Pouliot in 2020, titled Je me souviens (des premières morsures), were accompanied by a quotation from Roland Barthes taken from Camera Lucida. Nearby, Natacha Nisic’s video Plutôt mourir que mourir (2000) conveyed her quest for the traces of the First World War – an archaeology of daily pain, or a review of images and texts – in order to untangle the complexities of that devastating conflict. At the same time, in a sort of semantic counterpoint, Nisic asks herself questions to rekindle the fire of empathy: What is the colour of philosophy? Of history? Of emotions?

At the back of the gallery, on a small screen mounted on a tripod, was another of Vachon’s artistic interventions. Here, she translated, as a digital video incursion, a work by Martin Désilets, Matière noire, état 14 (2018), a print on aluminum of photographs of visual works layered so thickly that the result was pure black. This attempt at exhausting the photographic act resulted in a series of images so vibrant that they could be seen as a representation of the cosmos. In Vachon’s video, the original power of Désilets’s work is amplified. Its resonance becomes action.

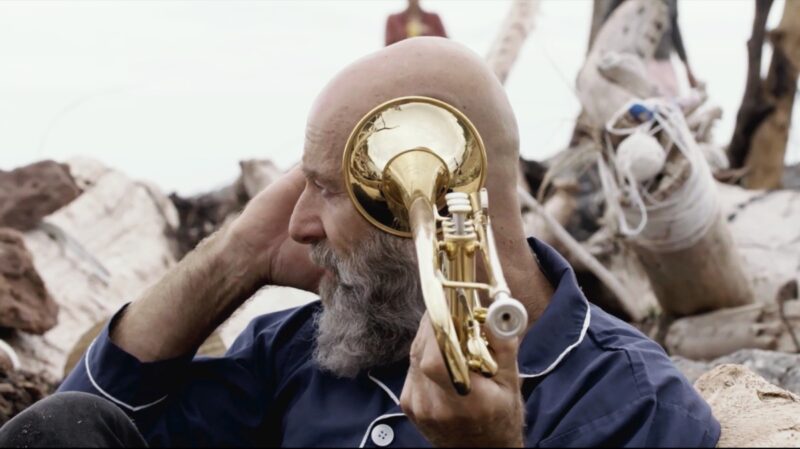

We then discovered the source of the crumpling-paper sound mentioned above. It was Ismaïl Bahri’s video Revers (2017), a conversation between the tactile and its representation. A man whose face we don’t see, possibly the artist, is sitting at a table. His hands feverishly make and unmake a ball of paper – a page from a magazine featuring pictures of idealized bodies – alternately hiding and revealing its content. As this almost ritualistic act is repeated, the paper crumbles into fine dust, which we see as a puff of smoke. To the side, a tuning fork was mounted on a light box, accompanied by headphones. A sound installation by Nicolas Bernier from 2014, Frequencies (a/archives), brought sounds and tangible material into contact, in a quest for balance between the rational and the sensory. In a small adjacent room, Daniel Olson’s video Take Five (2004), in which mirrors reflect the image of a man smoking a pipe from five different angles, explored the ideas of originality and reproduction.

The exhibition ended with Sébastien Cliché’s installation Le sommeil trouble de l’opérateur (2015). This fascinating work explores the mechanics of control and release. In an unending ballet, a mechanism releases magnetic tape, which slides down a metallic slope, forming fleeting arabesques at the bottom. At the heart of the installation, a reel-to-reel tape recorder, usually a symbol of memory preservation, is transformed into an agent of disorder. This sense of loss of control seems to give rise to self-regulation processes, like a poetic meditation on the paradoxes of spontaneity. Finally, we discovered the mysterious machine that produced the video in the first section of the exhibition. A camera and a screen unveil the very essence of the philosophical dilemma. The fictional figure of an operator embodies the tension between order and disorder. The operator’s invisible surveillance is essential to maintaining the fragile harmony of the system.

Philosophical in tone, the exhibition was revealed as an agitated landscape. Its intelligent and profound staging functioned as a laboratory for the most fundamental questions. Borrowing from great masters and schools of thought, Vachon triggered, in a very personal way, mechanisms that call upon knowledge, and she presented them with generosity. The interplays that she created put cosmic and human scales on an equal footing; we might even wonder if, for her, these scales actually exist. She invents atlases within atlases, which replicate without end. One question remains: are these atlases words? Translated by Käthe Roth

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: The Atlas: A Word]

NOTES

1 The exhibition, a choral and trans-disciplinary project by the artist-curator Suzan Vachon, was presenred at the Musée d’art contemporain des Laurentides from January 28 to April 28, 2024.

2 Events as we understand them from the perspective of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

3 Force field as in Leibniz’s metaphysics.