[Summer 1997]

Alain Laframboise’s photographic stillevens are imbued with the specific rhetoric of the hyper-codified genre that is still-life: the deliberate placement of inanimate and enigmatic objects; directional, dramatic, theatrical illumination (chiaroscuro); flat, shallow background against which the objects are projected; striking trompe-l’œil effect (which photography does well); hidden symbolic content that invites reflection on the finite and ephemeral character of life.

par Jocelyne Lupien

For me, there is only one criterion for telling if a photograph is good: if it is unforgettable.

⎯ Brassaï

It was in Paris in the seventeenth century that painter Charles Lebrun, founder of the Académie royale de peinture, set the hierarchical scale of painting genres. He placed still-life at the bottom, since the simple reproduction of immobile objects – flowers in a vase, remains of a meal, books – was considered to have little honour compared to great religious, political, or mythological paintings. At the same time, however, Caravaggio was noting that painting inanimate or immobile objects – stillevens, as they were called in seventeenth-century Holland – required just as much skill and time as painting portraits of people, gods, or nymphs. The goal of a still-life was not only to reproduce nature faithfully but to portray hidden symbolic content with a moral or religious connotation – as Panofsky has explained so well. Both updating and parodying this tradition at the same time, Alain Laframboise’s photographic stillevens are imbued with the specific rhetoric of the hyper-codified genre that is still-life: the deliberate placement of inanimate and enigmatic objects; directional, dramatic, theatrical illumination (chiaroscuro); flat, shallow background against which the objects are projected; striking trompe-l’œil effect (which photography does well); hidden symbolic content that invites reflection on the finite and ephemeral character of life.

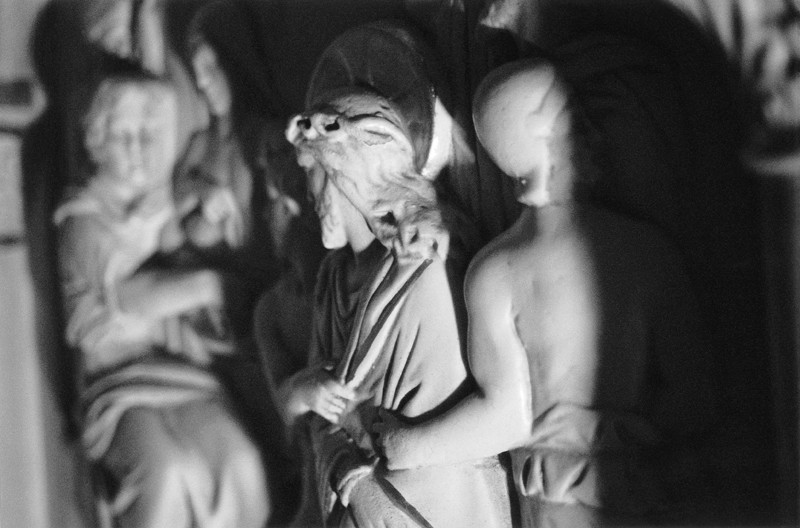

The objects in Laframboise’s images are, however, “modalized” by a unique spatial rhetoric that creates ambiguities of scale, which, in their turn, generate perceptual ambiguities and cognitive dissonances replete with troubling effects. In one photograph, the caskets – funerary icons – seem immense at first glance, but then, when we view them from closer, we realize that their “hysterical” placement reveals their true nature as models of reduced size. In another image, the close-up portrayal of blurry objects – evoking peripheral vision – creates a proximation of an unbearable intimacy, while in the same image a small architectural maquette tries to make us believe that it is monumental. Chiasmus. And there are dissonances of scale, but also iconic dissonances visible in yet another photograph – which parodies Zurbaran while paying tribute to him – in which the linear presentation of three objects (a mask, a doll, and a human skull) evokes the syntagmatic structure of a sentence aligning its words one by one, stratifying and slowing the time it takes to perceive and decipher the meaning of the image.

The function of representation is certainly very important in these photographs, which are shot through with fetishized objects, but Laframboise has understood that this function is based less on the object’s resemblance to its model than on its power to evoke it.1 These images take the place of what they represent – they possess a mana – but this is not their function, since they also have the power, it seems, to act on the people who look at them, in the sense that they can contain the object portrayed and the viewer in a single envelope.2 We damage ourselves, we dive in and lose ourselves in them – these seductive, persuasive images – because we recognize ourselves in them.

We are in these images. If we have the feeling that they resemble us, it is because the images dreamed up and exhibited by Laframboise provide an envelope for our own thoughts, dreams, and fantasies.

On another level, one may wonder if Laframboise’s photographs are not in fact screens that allow us to protect ourselves from being stolen away by objects and the unbearable reality they evoke. Indeed, the caskets, the tombstones, and the skull are brandished as if they were magical fetishes capable of pushing death away. The same device is used in the image in which two tiny statuettes, sitting above a golden abyss, seem subjugated (petrified) by a dazzling apparition – invisible to us – that overwhelms them, bathing them in a Byzantine light. Does this image not provide us with a way to undergo, through interposed icons, an intense mystical experience?

Alain Laframboise’s Visions Domestiques prove to be representations of his own perception of objects that, ordinary as they are at first glance – even banal, as the artist says – are transfigured by the semiotic process of the photographic image into objects that are fetishes or fetishized and charged with the weighty mission of communicating to us the unsayable and unrepresentable – death, the flash of mythical joy and ecstasy. Nothing less.

2 Ibid., p. 164.

Alain Laframboise has been exhibiting his work, consisting of mixed-technique “boxes” as well as photographs, since 1983. He has shown in Canada and Europe, and his works are in public and private collections. With Normand de Bellefeuille, he co-authored Notte oscura, a book of photographs and writings (Éditions Noroît, 1993). He co-directed Trois, the publishing house and the magazine, from 1985 to 1996. As an art critic , he has contributed to many magazines and publications, and he has helped to organize exhibitions. A specialist in the Renaissance and Italian Mannerism, he has been teaching art history and theory at Université de Montréal since 1976.

Jocelyne Lupien is a professor of art history and theory at Université du Québec à Montréal. Since the early 1980s, she has written a number of texts on contemporary art that have been published in catalogues, as book chapters, and as articles, notably in the cultural journals Visio, Spiral, Espace, Vie des arts, Etc Montréal, Parachute, and Protée. With a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, she is currently writing a monograph on contemporary art in Quebec since 1980. In the autumn of 1997, she will be curator of the exhibition Anamorphose, arcimboldesque et images spéculaires at Galerie de l’UQAM.