[Winter 1993]

by Ken Straiton

I have always been interested in cities. I love the country, but the city is food for thought and for my eyes. The real subject of cities is what interests all of us the most: human beings.

For all the castigation of the city versus nature, the paradox is that cities are entirely man-made. As we are inescapably part of nature, we cannot really think of cities as unnatural. Most people seem to agree that the city is a kind of necessary evil, but why are they made this way? Maybe cities as they are, are man’s true natural state. If something about Tokyo bothers you, remember that it has been created entirely by people who live there.

Tokyo is different than the North American cities that I grew up, and especially the European cities I have come to know. In this century Tokyo has not only exploded in size, but has experienced three great waves of destruction and reconstruction : the Kanto Earthquake, World War II, and the ‘Bubble’ of the 80’s. Because each wave has, in turn, erased previous incarnations of the city, Tokyo has had the opportunity to escape the past and remake itself in its own contemporary image, three times in living memory.

The newness, and sense of impermanence of Tokyo, led me to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, islands of tradition in the changing sea of the city. Permanence of one kind or another are their stock in trade. After printing Tokyo Stories, I was surprised how many scenes were in or about cemeteries. I realized that these were places I returned to as touchstones in a shifting environment.

Photographing a city can give a portrait of a society. I work from the assumption that the man-made environment, no matter how humble, is invested with meaning, has some unavoidable content of human expression. I am especially interested in the monumental, because it is a conscious attempt to invest the material with a form that evokes the spiritual, or aims to overawe with the implicit power of the builders. Tokyo’s prodigious infrastructure also embodies some of these qualities, as a monument to 20th century engineering and ambition.

The infrastructure in Tokyo dominates the cityscape. The natural contours of the land and rivers have been obliterated, leaving and exposed nervous system of railways and wires and concrete, forming a web which overshadows those caught in it. The city as an organism has taken on a life of its own.

Tokyo is a melange of scales and styles, a welter of wires and signs and lights, competing for your attention; a visual and sensory overload. The apparent randomness and constant, restless ferment, is part of the essential character of Tokyo. With its relentless construction and constant motion, there is a kind of insecurity in its progress, and sometimes a poignant sense of loss. Increasingly, the traditions of the culture seem to exist in an alien environment.

As far as my emotional relationship with Tokyo: I think I am like anyone who has lived here. It is impossible not to both love it and hate it. I respect the elegant traditions of Japan, and find inspiration in the vibrancy of Tokyo today. I have felt compelled to document it, to make a record of something special, and to show Tokyo to those who don’t know it, as something more complex than the misapprehensions and stereotypes with which it is often viewed.

I constantly ponder the problems of the urban situation. Perhaps because I studied social psychology and pursued architecture, I am always trying to imagine some ideal balance amongst the many competing demands of a functioning urban society. All this, and concern for the future direction of Tokyo’s development, have led me to comment upon what I see around me : Tokyo stories.

About the development of the series

All of these photographs were made in Tokyo or its suburbs, where I have spent most of the last eight years. In the process of coming to understand Tokyo, and working on Tokyo Stories, the character of the city has led to a means of interpreting it.

The experience of the city, especially for a newcomer, is like a watching a film spliced together of random outtakes from a confusion of different movies. Just when you think you can follow the film — WHAM — you are looking at something new. In fact, even as I got to know Tokyo, like some kind of multi-screen projection, the scenes and narratives and layers of information became recognizable, but never coalesced into a coherent whole.

I was never satisfied trying to document Tokyo in a single conventional image. It seemed misleading to take one piece out of a continuum: it was too specific, too narrow. Snipping a freeze-frame here or there out of the film, ‘Tokyo’, was not enough to describe the intensity of experience and confusion of information. The panorama proved effective at capturing the sweep of the city, providing a context for the myriad scenes and details with their seemingly paradoxical coexistence.

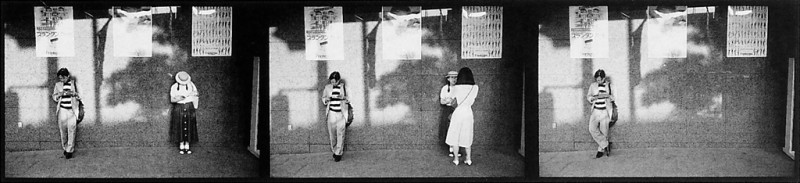

For showing more intimate scenes and little human events, I came upon the three-frame sequences. I liked the lively quality of their narrative form, or the way that, in a kind of shorthand montage, they give an expanded picture of a scene.

When the sequences are combined with the panoramas, the dialogue amongst the images suggests the layering of Tokyo: mental and social, as well as historical and physical.

Juxtaposition demands a re-examination of each of the elements and expands the possibilities for their interpretation. There is no fixed formula for the relation between the panorama and the sequence below. It is usually both formal and symbolic, and sometimes associational. In the end I used only those combinations that I felt worked strongly and created some new meaning.

In regard to the shooting in general: with Tokyo Stories I took a more removed, documentarist’s approach, than I had with previous work. A major motif is the organization of the city itself, so I had to step back far enough from the scene in front of me to let its own form be visible, and to let Tokyo tell its own story.

Born in Toronto, Kenneth John Straiton started off at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. While studying at the University of British Columbia, he developed a great interest in photography and in cinema. He subsequently moved on to teach at the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Straiton is also an avid traveler, his greatest love being Europe, followed by Asia as a close second. He currently lives in Tokyo. Straiton’s images enjoy regular exposure in Japan, North America and in Europe. In February 1993, his Tokyo Stories collection was exhibited in the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo.