[Summer 1995]

by Jennifer Couëlle

At times, it seems that the most haunting images are those that, at first glance, appear to be innocuous – the very type that one would least expect to re-envision repeatedly, as a disturbing dream quietly recurring. Blatantly dramatic imagery is easier to identify and, therefore, to classify and be divested of. Its strength lies in its capacity to generate emotions and create visual impact upon initial contact with viewers. However, in those other images, made purposefully misleading by their muted or seemingly inane subject matter, drama is provided by an underlying sense of uneasiness – one that is perhaps more difficult to come to terms with.

Previous photographs by Blache, in the tradition of documentary or travel photography, have included series of “context portraits,” subjects informed by their environment. These projects were carried out approximately from 1985 to 1990, at which time the artist’s production began to evolve towards the landscape. In a series of portraits of Blache’s infant son, settings – usually exterior – acquire considerable importance, taking on an existence of their own, one that is parallel, rather than subservient or intrinsically linked, to the human subject. Formal composition begins to appear as an inevitable component for these “backdrops” turned subjects. Surrounding worlds are portrayed as structural fragments, as webs of shapes and lines, singled out and shot at close range.

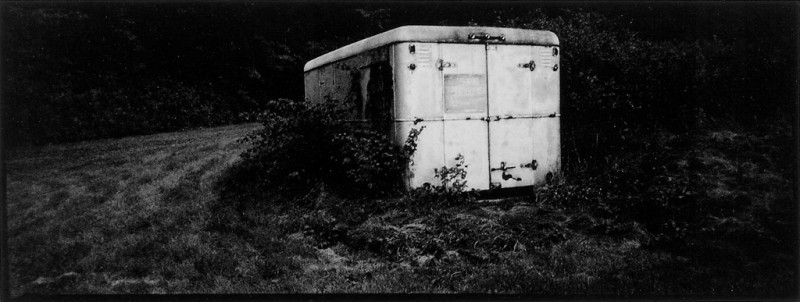

By 1993, Blache had purged the landscape of human form, at least in its physical representation – although the sites are now devoid of faces, human presence is still part of the picture. In the body of work presented in this portfolio, Nature and Culture are tacitly at odds. In one image belonging to a diptych, bleakness emanates from the “domestication” of a grove of aligned apple trees around each of which the grass has been closely mowed. Seemingly estranged from the very ground in which they are rooted, the circumscribed trees become akin to the similarly mowed-around dingy trailer – a patch of square-shaped light – inhabiting the field of the grove’s photographic counterpart.

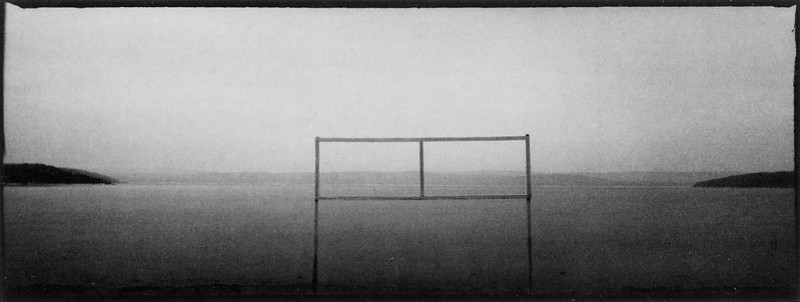

In another photograph, where a solitary two-part rectangular structure – vaguely reminiscent of a volley-ball net or of the framework of a roadside billboard stripped of its sign – stands erect in the centre of a vast, wide-open horizon of mist, the geometry of man and nature are simultaneously paralleled and opposed. Although they formally interact, the gap between them appears unbreachable. They cohabit in unresolved stillness. And emptiness gives way to ascendancy, as the void spaces of the rigid silhouette – resembling the lenses of a pair of large glasses – re-create and appropriate the very view that their supporting structure has obstructed: in their frame, they enclose segments of the distant horizon against which they are set.

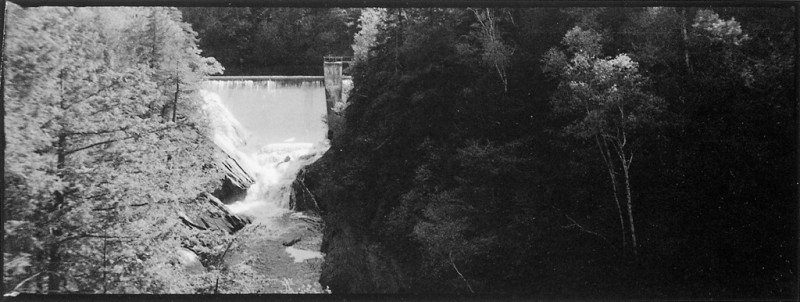

The unusually small panoramic format of many of these photographs is obtained by using a “cheap,” plastic Pix Panorama camera, which registers the image horizontally across the middle section of the 35 mm negative strip but, unlike the traditional wide-angle lens, is unable to capture full detail across the entire surface. As a consequence, the extremities of these elongated images remain more or less blurred, while the vanishing points of the centre of vision are accentuated. The overall impression is one of a panoramic vista encroached upon by sketchy, as-if-drawn shadows. And although the artist’s manipulation and distortion of light create a low-contrast, somewhat unifying greyish colouring – rendering the photographs almost painterly – the visual tension between the more sombre edges and the lighter, central point of focus remains. It would seem, then, that these “false” tone-on-tone panoramas are all the more suited to the conflictual nature of their subject matter. And disavowing any notion of the romantic landscape, in one emblematic image, the (human-made?) stream runs alongside the post-and-wire fence of fallow fields unto its final vanishing point.

Pierre Blache studied photography at Concordia University of Montreal and at Collège de Matane. His works are currently exhibited inside and outside Canada. He is also working as a curator for the Mois de la Photo à Montréal and director of Galerie VOX.

An art critic and translator specialized in contemporary art, Jennifer Couëlle holds a B.A. in Art History and an MA in Arts Studies from l’Université de Québec à Montréal. She has worked as exhibition coordinator at the Saidye Bronfman Centre for the Arts and at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Since 1989, she has acted as an independent curator and has published numerous reviews in Canadian cultural periodicals as well as catalogue essays. She is currently working as an art critic for the Montreal daily Le Devoir.