[Spring 2005]

I Was Overcome by a Momentary Panic at the Thought that They Were Right: Documents from the Nassar Files in the Atlas Group Archive

Art Gallery of York University, Toronto,

15 September–14 November, 2004

Mortar shells were almost a daily occurrence the year I was posted in Lebanon as part of my service in the Israeli Defence Forces. Looking over from my base to what was then referred to as the Security Zone (southern Lebanon), I was forever overcome by both trepidation and awe. The landscape was a huge façade behind which lay unpredictable players. It was a stage where performances took place at unregulated times and featured countless actors. My job was to let everyone know when the show was about to begin. But it was nothing like in the theatre. Plays end and the lights go on. Scripts have good guys and bad guys. The few Lebanese I met in Israel were nothing like in the stories. Nothing ever is.

After I completed my army service, it took me a while to stop ducking automatically upon hearing a loud “boom” (it was usually somebody dropping a book in the lecture hall). It is difficult to explain an experience like war to someone who has never faced it – especially to eager young students convinced of the “madness” of it all and the veracity of their political views. The complexities are so great. So when I come across art that reflects the subtlety of war and politics, I want to tell the world that it is more useful than the ton-of-bricks bipolar philosophy of popular media-lustre types.

Such is the exhibition by Walid Raad and the Atlas Group, organized by the Art Gallery of York University. Dr. Fakhouri and Mr. Nassar donated their archives to the Atlas Group, a collective and institution based in Beirut and New York whose aim is to document “contemporary history.”

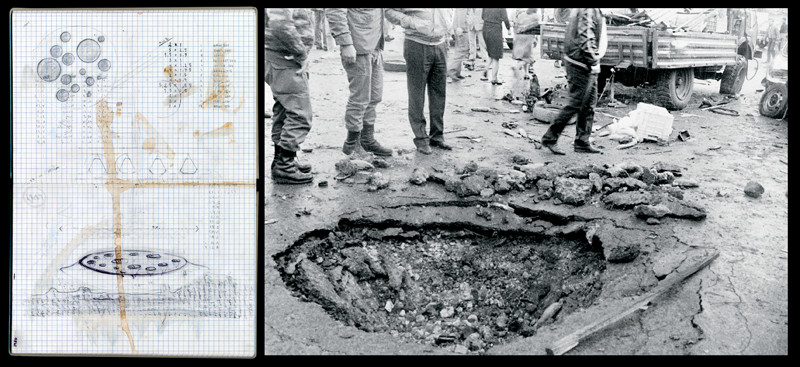

Car bombs were as traumatic as they were common in Beirut throughout the war, and Mr. Yussef Nassar has documented them extensively. He is a demolition expert, and his car-bomb archives are presented in My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair: Engines, 1996–2004 (2004). This is a collection of one hundred photographs, taken by both amateurs and professionals, of car-bomb engines. According to the wall text accompanying the photos, the engine is the only part of the car that remains intact after detonation, and it is often projected high into the air. Photographers race to be the first to locate the engines on rooftops or in neighbourhood streets. Mr. Nassar gathered these photographs from 1977 to 1991, and they are now housed at the An Nahar Research Center and the Arab Documentation Center. The artist presents reproductions of these photographs, both front and back, for our inspection. True to their archival purposes, the backs of these images hold general administrative information, such as the photographer’s name and the date, mostly hand-written or ink-stamped. Along with this work is shown I Was Overcome by a Momentary Panic at the Thought that They Might Be Right: 1986 (2004), a sculptural installation referring to craters left in the ground by car bombs with corresponding photographs on the adjacent wall (taken from Mr. Nassar’s extensive notebooks). These “craters” are depicted in relief on the floor, spot-lit with small bluish lights suspended on cords hanging from the ceiling. The result looks almost like the surface of the moon. These two works are on exhibit at the Art Gallery of York University, in conjunction with another exhibition of Walid Raad and the Atlas Group at Prefix Gallery.

At Prefix is a collection compiled by Dr. Fakhouri, a Lebanese historian. His archives include two videos, photos of himself in Paris in 1956, and two notebook archives. One scrapbook documents Lebanese historians’ betting at horse races. But the historians were not betting on the winner; rather, they guessed the precise second when the photographer would photograph the winning horse crossing the finish line (he would take only one shot). The other logs exact details and photographs of 145 cars that correspond in model and colour to ones used throughout the civil war as car bombs, along with statistics on each bombing. These pieces are closely related to the ones exhibited at the Art Gallery of York University.

These two men attempted to comprehend the trauma surrounding them by cataloguing it and studying it scientifically – so much so that it almost became an obsession. Almost, but not quite, because these men don’t really exist. The “archives” were produced by Walid Raad, under the pseudo-institute/collaborative body that he created, the Atlas Group. Raad goes to great trouble to legitimize his archives by providing signifiers of institutional authority: a gallery setting, didactic panels, institutional stamps, cataloguing systems, even a linear wall chart. He has created a fictitious history for his work. It is so effective that had I not been informed so, I probably would not have known that the benefactors of these archives do not exist as individuals (although the horse-race photos were quite a stretch even for someone as gullible as I). Knowing this, I began to question everything in the show: was there a civil war in Lebanon? Were car bombs really that common? And in this seeming fault, these easily accepted lies, Raad’s brilliance shines; he beautifully illustrates that the process of writing history, of creating a shared culture, and of disseminating information is just that: a process. It is subjective. We create our history. And this is the most empowering tool for self-determination.

In fact, Raad is so aware of this process that he is fascinated by the moment of its inception: what Cartier-Bresson referred to as the decisive moment. The precise instant that changes our lives is one that is determined as much by the photographer as by the terrorist. Releasing the shutter resonates as much as activating the detonator. Raad’s vertiginous video sequence of photographs of instants when he falsely believed that the war was over is actually a window, however fleeting, onto Lebanese life. The most illustrative and elegant of the works emphasizing the decisive moment of the photograph intersecting with that of the creation of history is “Missing Lebanese Wars,” the archive of Lebanese historians’ bets on the specific second that the photographer will choose to photograph the winning horse. The seemingly arbitrary moment of the photograph, not the winning horse or its time in the race, is of consequence here. Picture the tiny action of releasing a shutter or activating a bomb, as tiny as the click of a computer mouse, having repercussions growing and rippling outward into the world, its effect multiplying exponentially. The camera has been compared to the rifle, but in our age of media consciousness the camera is comparable to the bomb.

Raad’s horse race is an allusion to the “contemporary history” that he is investigating. Or perhaps it is an allusion to the war that we are all running in, waiting for the instant of peace. In the race, as in life, experts can only guess at what will result in print. Be it one arbitrary instant or another, that moment will manifest itself in a continued historical construction.

Chen Tamir is a Toronto-based art critic and curator.