[Spring 1999]

In Jeff Wall’s photographs, there is an attraction and deflection – a push and pull of ideological thrusts and formal repartées – that entraps the viewer. Standing in front of a large-scale back-lit Cibachrome, one is caught in the middle of an exquisitely choreographed duel between painting and photography.

by Dot Tuer

In the Lacanian sense of the gaze, one sees oneself seeing oneself looking at a photograph as if it is an old master’s painting. Like a moth to light, the eye is drawn to the luminosity, the scale, the staging, the detail. Yet once the viewer is drawn in, the content of the images is disconcerting. What is to be made of the toying with art history, the visual puns on race and class, the baroque splendour of bag ladies and trench warfare, the nondescript grimness of the urban setting? Is the subject matter intended as a commentary on the relationship between representation and ideology, or as a strategy to empty the image of any meaningful signification? Is this social critique or cultural cynicism?

The ambiguity of Wall’s images, of course, is precisely their lure. The destabilization of intended meanings and readings turns the gaze of the camera back upon the viewer. To view one of Wall’s works is to become an active participant in a mise-en-scène. Like a private investigator or street-beat reporter, we are the witness to the dramatic moment. The flash has just gone off. The figures are slightly stiff. They seem to be either startled by the sudden intrusion of the lens, or defiantly facing down the camera. As viewers we know, of course, that the visceral sensation of arrested motion is a product of an elaborate faux-document set-up. The drama lies in the tension between artifice and realism, rather than in the subjects themselves. There are no actual furtive glimpses of a dark and forbidden side of urban existence, just mundane moments heightened through the artist’s sleight of hand. From the point of view of production rather than reception, the images owe less to a documentary tradition of photography than to Tinseltown illusion; they are created in the manner of film sets, replete with lighting crews and actors. Yet, at the same time, there is this contradictory urge in the spectator to “read” the photographs as real rather than fiction. Why else would a photographer go to so much trouble to stage such ordinary mises-en-scène?

Precisely because there is nothing compelling in the images as documentary icons, the question arises of where the compulsion to look comes from. Is the reception of the work predicated upon voyeurism or consumerism or both? Has Wall made voyeurs out of consumers, or revealed a commodity fetishism in the act of seeing? Wall’s debt to advertising light boxes is well known; his oft-repeated story of experiencing an artistic epiphany while looking at Velázquez in the Prado has become almost apocryphal. In his combination of these elements, he constructs a field of vision in the art world that parallels that of Benetton’s in mass culture. Benetton sells clothes through the use of conceptual photography. Wall sells art through the use of conceptual advertising. Both have learned their lesson well from Warhol, each blurring the boundaries between the territories of taste and fashion.

When Douglas Crimp wrote his seminal article “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism” (October, No. 15, 1980) announcing the arrival of postmodern photography almost twenty years ago, he called upon Benjamin’s concept of the aura and the theatricality of minimalist sculpture to chart his way through the work of artists such as Cindy Sherman and Sherri Levine. For Crimp, photography was the ghost in the machine haunting modernism and the museum, threatening the sanctity of art and the authenticity of the original through its endless potential for reproduction. Institutions such as the MoMA tamed the threat of mechanical reproduction by valourizing the unique vision of the photographer as artist. The camera’s eye was embodied with subjectivity and individualism; a signature style corresponded to the distinctive gesture of the brush stroke. In the hands of the postmodern photographers, however, Crimp argued, “art” photography became something else as well. It created a desire for the aura yet subverted a claim to originality by producing images that are “always already seen” – that is, images appropriated from mass media and images that mimic a field of vision framed by cinema or artistic modernism.

In Wall’s work, both the modernist and postmodernist paradigms described by Crimp are at play. Through the duel he stages between photography and painting, he recuperates the aura of the original and elevates the status of his work to that of high art. Collectors and museums form a queue to possess limited edition versions of what in theory could be mass produced. His work hangs in contemporary-art and not photography sections of museums. The postmodern photographers that Crimp wrote about – Sherman and Levine – have also taken their place in the museum canon; the difference between them and Wall is that his work never claimed to undercut the aura through appropriation. Rather, his was a resolute and unapologetic project to transform – not mimic or appropriate – the indexical function of the photograph into an art form. Rather than exposing the spectacle of the mass media, he uses the medium to aesthetize the ordinary, mocking our desire for verisimilitude. Hence the seeming amorality that permeates his work.

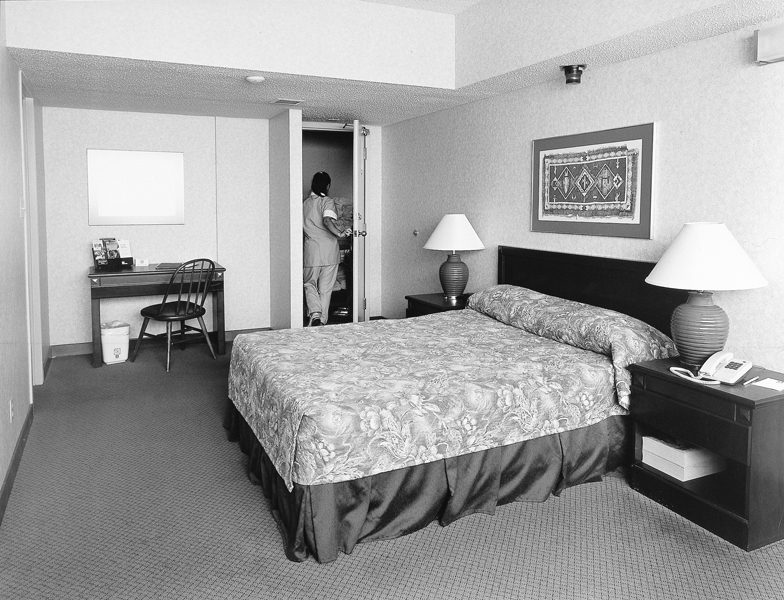

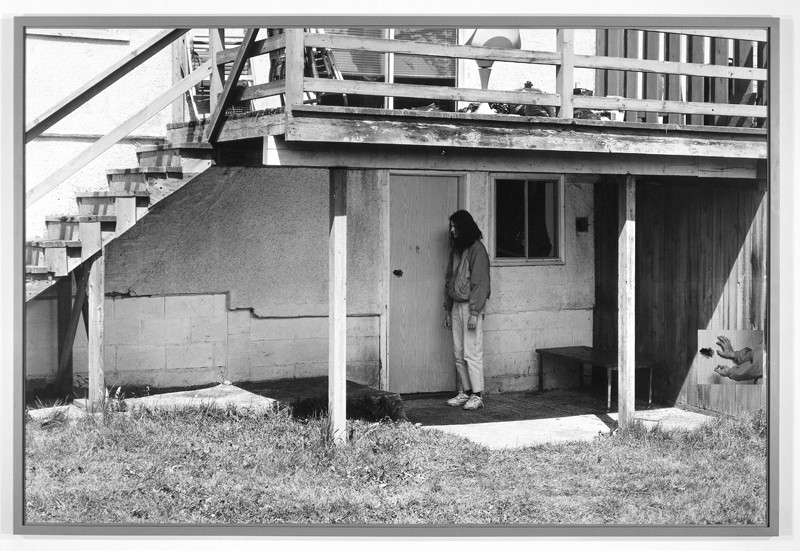

In Wall’s black-and-white photographs, there is a seeming departure from the large colour format associated with his work. The indexical relationship of these images to a documentary tradition of photography – one that stylistically echoes thirties depression images from the Farm Security Administration project – is atypical of his strategy. In general, Wall circles outside the canon of art photography for validation, referencing art history, cinema, advertising. I once heard someone comment (or did I read it?) that Jeff Wall’s cleverness lay in giving the Vancouver urban landscape a signature representation – creating an visual imaginary of Canada in the same way that the impressionists painted the environs of Paris. Yet, in his black-and-white photographs, the staged shots of housekeeping staff servicing the international flow of business, or of disaffected youths who oppose hip-hop codes with skin-head postures, could as easily be located in Scarborough or Montreal or Burnaby as Los Angeles.

When Sherri Levine took a photograph of a Walker Evans image and signed her name to it, she intervened in an arena of exchange value and meaning. Through her gesture of appropriation, she called into question the veracity of the document and highlighted the worth of an auteur signature. Wall’s allusions to the classic era of American documentary are more subtle, and double-edged. What is at issue here is less veracity or the aura of the original than the way in which the mnemonic properties of photography stand in for history. Perhaps with his black-and-white spin-offs he is constructing a context for his work to be looked at and seen – like that of Walker Evans – as the signature for an era. What Evans was to American modernism, so Wall will become for postmodernism: his work a distillation of a historical moment through the imaging of the bland surfaces and banal malaise of North American everyday life. Whether his photographs will succeed as a synthesis of postmodernity is open to speculation. As much as one may try to orchestrate representation, there is no way to guarantee its future reception. But in Wall’s deft play on codes and desires, he raises the important question of whether the ubiquity of the photographic image is re-engineering a visual register of the past and present.

Jeff Wall lives and works in Vancouver. Since the early eighties, he has become an important figure in the international contemporary-art scene. His works have been featured in many solo and group exhibitions in galleries, museums, and contemporary art biennales throughout the world. The Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal features a major exhibition on his production during the nineties until April 25, 1999.

Dot Tuer is a writer and cultural historian. She is an instructor at the Ontario College of Art and Design, where she teaches, among others, courses on the history of photography and postmodernism. She is currently completing a doctorate in history at the University of Toronto.