Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

18 September to 15 December 2013

By Ivan Tanzer

Although he did not set out to organize a comprehensive history of activism in Aboriginal art, guest curator and National Visiting Trudeau Fellow Steve Loft has mounted a significant exhibition that strengthens the living discourse surrounding Aboriginal art production. Drawing upon select historical images from Ryerson’s Black Star archive as starting points, Loft emphasizes the unbroken chain that connects decades of social, political, and artistic activism. Contemporary prints, mixed-media works, and video installations are contextualized with archival imagery from three major turning points in recent Aboriginal history: the Alcatraz Occupation (1969), the Wounded Knee Occupation (1973), and the Oka Crisis (1990). The exhibition brings together a group of artists who engage in “articulate resistance, a form of social engagement specific to the history of colonization and continued racism.” 1

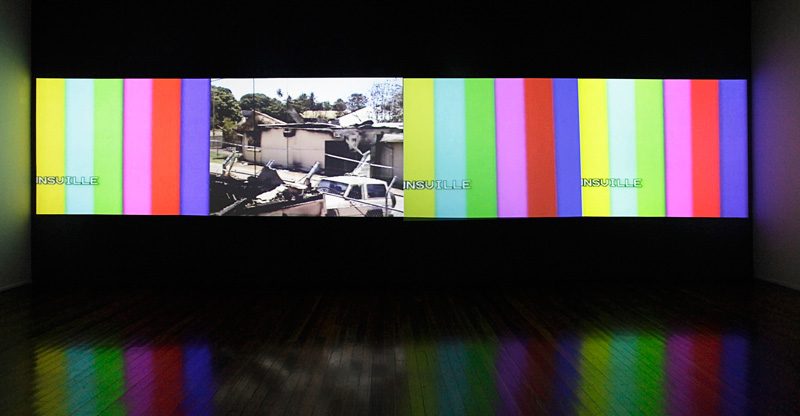

Prominently displayed on the new media wall leading to the main gallery space, Jackson 2bears’s Mythologies of an (Un)dead Indian challenges preconceptions and assumptions. This large video mashup piece layers the most blatant of old Hollywood exploitative cowboy-and-Indian clips (featuring powwows, tomahawks, chanting, and so on) with subversive audio and visual samples that testify to 2bears’s skills as a DJ and weaver of visual storytelling. This absorbing hybrid video artwork is equal parts music video (A Tribe Called Red comes to mind) and highly incisive critique of Aboriginal stereotypes and media portrayals.

In the main gallery and annex, eight contemporary Aboriginal artists and one non-Aboriginal artist are featured. Loft’s decision to include a non-Aboriginal artist’s work is unexpected, but it adds a layer of complexity by challenging the visitor to question his or her own identity in relation to the curator’s decision to include and exclude. Alan Michelson’s RoundDance II, a four-panel video installation, mounted at cardinal points around the gallery, provides a uniquely inclusive experience that contrasts strongly with many of the more directly oppositional pieces. As dancers move seamlessly from one monitor to the next, you find yourself a participant at the centre of a living celebration of Aboriginal spirituality, aesthetics, and political activism. Contrast this work with Sonny Assu’s The Happiest Future #1-10, posters inspired by propaganda from the world wars and the communist era, and you begin to get a sense of the layers of meaning inherent in the exhibition. Assu’s stylized posters subvert and challenge our belief that Canada is, and always has been, a tolerant society free of discrimination. His recontextualization of the words of Duncan Campbell Scott, former head of the Department of Indian Affairs, who wrote, “The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government,”2 should give visitors –especially non-Aboriginals – serious cause for reflection, as it is ultimately understood as a clarion call for continued resistance.

The difficulties and trials faced by Aboriginals as reflected in the artworks are not limited to a Canadian perspective. Ghost Dance also highlights the plight of Aborigines in Australia and explores the historical and contemporary significance of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the United States. Dana Claxton’s research into her Lakota Sioux family history led her to uncover declassified FBI documents at the New York Public Library. Her series of four large-scale gelatin silver prints (AIM #1-4), enlargements of these artefacts that are complete and unaltered except for glaring redactions, illustrates just how actively and openly the American government opposed organized resistance by Aboriginals. The fact that there are striking similarities in the treatment of Aboriginals internationally makes forums for meaningful discussion, such as this exhibition, even more important in the movement toward real change.

At its core, “Ghost Dance examines the role of the artist as activist, as chronicler and as provocateur in the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights and self-empowerment.”3 This important and thought-provoking exhibition builds upon a living and vibrant tradition by pushing back against the systems that seek to limit and control it.

2 Duncan Campbell Scott, “Indian Affairs, 1867-1912,” in Canada and its Provinces, Vol. 7, Section 4 (Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Company, 1914), 622

3 Steve Loft, Ghost Dance exhibition catalogue.

Ivan Tanzer is a freelance writer and artist-development agent based in Toronto and Montreal.