By Sébastien Hudon

As far back as 2002, multidisciplinary artist Adad Hannah was citing a work by French sculptor Auguste Rodin in his own work. It has been thirteen years since he produced Stills, composed of video captures of Rodin’s first bronze, The Age of Bronze (1877). At the time, no one would have guessed that this was the first manifestation of Hannah’s unique and constant fascination with the Parisian master – a fascination that continues today. Indeed, references to Rodin, who would create the now-celebrated The Thinker, have punctuated Hannah’s production, as he began to integrate them into tableaux vivants, both photographic and videographic, in 2005.

Hannah is currently presenting to the Montreal public what seems to be a synthesis of this creative process in a new piece called The Burghers of Vancouver1. First displayed at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, this video installation, inspired by The Burghers of Calais (a well-known sculptural group by Rodin) may in effect be understood as the culmination of reflections that have preoccupied Hannah for the last decade.

Before going further, we should note that The Burghers of Vancouver is directly related to a rich doctoral dissertation 2 written by Hannah, of which this article gives only a brief overview; there is not enough space here to embrace the entire conceptual depth of the work. It should also be noted that Hannah collaborated with filmmaker Denys Arcand on a number of aspects of conceptualization and production. This was the second time that they worked together, following their joint experiment for the exhibition Big Bang at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2011.

The installation The Burghers of Vancouver takes its title, and its inspiration, from a well-known statuary group of which there exist only twelve bronze copies in the world.3 Begun in 1884 and inaugurated in 1895 in front of the Calais town hall, The Burghers of Calais is a tragic and expressive allegorical piece involving six male figures, and it contributed greatly to Rodin’s renown. The grouping refers explicitly to a heroic historical event that is said to have taken place during the Hundred Years’ War, a conflict between France and England during the Middle Ages.

In August 1347, the fortified town of Calais, which had been besieged by King Edward III of England for almost a year, was on the verge of being taken by force. The town’s population was desperate. In order to negotiate magnanimous terms for surrender with the British crown, six wealthy residents proposed that they be executed as a military toll; their sacrifice would save the lives of the other townspeople. The sculpture portrays the moment of departure for the enemy king’s camp: with ropes around their necks and one holding the keys to the town, the six men are tormented by the idea of the death to which they are ineluctably delivering themselves. Touched by this extraordinary demonstration of courage, the king’s French wife, Philippa de Hainau, convinced her husband to spare them at the last moment.

The Burghers of Vancouver

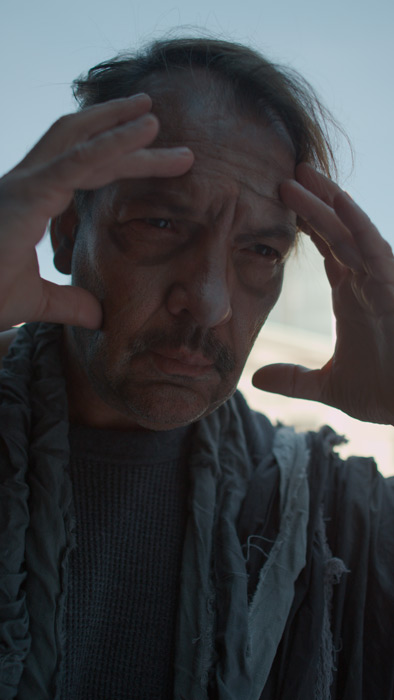

This is thus the point of origin for Hannah’s artwork, which is in direct extension to his previous work and bears a certain thematic continuity with Les Bourgeois de Calais: Crated and Displaced (2010). An abstract transposition of Rodin’s work, The Burghers of Vancouver is deployed in the exhibition space through a device composed of six television sets placed within an imaginary circle several metres in diameter. The screens are turned vertically and face outward so that visitors can appreciate the video images by walking around the circumference of the grouping, just as they could walk around the real sculpture in other times and places. On these screens, in alternation, are presented live shots from a bronze original of The Burghers of Calais and images from the stories of the “Burghers of Vancouver” – six residents of the city: an unemployed former sawmill worker who had moved to Vancouver, a junkie in rehab, an ex-accountant convicted of fraud and just out of prison, a poet, a skier, and an elderly Asian woman.

These six Vancouverites are asked to embody the figures in the original sculpture. On each screen, we follow one of these characters in his or her daily life, but also as he or she prepares (makeup, costume, rehearsals) to take part in a tableau vivant. The tableau vivant is thus inscribed in a fiction inserted into the installation, as well as forming the plot and narrative denouement for each of the characters’ stories.

It is an interesting artifice, as Hannah and Arcand have not only imagined a setting for the tableau vivant and doubled it with a performance functioning as a sort of prologue, but they have also combined their individual approaches into a limpid and particularly coherent whole. The conceptual connection with Hannah’s previous works is discussed above, and a similar cohesion is clear for Arcand, an experienced filmmaker, director of Réjeanne Padovani (1973), The Decline of the American Empire (1986), The Barbarian Invasions (2003), and Days of Darkness (2007), among others. It is obvious that in Arcand’s work, the characters’ critical resistance to or desire for emancipation from the erosion of their socio-economic power always has symbolic value. His films often evoke well-known events from classical history (the fall of the Roman Empire, the invasion of the “barbarians,” references to Julius Caesar, and so on). In addition, we cannot help but note a certain “cinematographic” tone, beyond live cinema and documentary, which no doubt echoes the gaze of the young Arcand. As in the incisive essays from his early days at the National Film Board, the proximity with a head-on, raw reality that colours some segments of The Burghers of Vancouver – live scenes of the characters’ daily life – says much about his role in the production of the project.

The selection of actors, who were cast from responses to a newspaper ad, provides a convincing contrast with the six “burghers” in the Rodin sculpture, similar to the situation of the models that Rodin used, taken “from the people,” to produce his grouping. A certain tension arises from the fact that these walk-on actors are not aggrandized or heroically idealized by the creators of The Burghers of Vancouver. Although they received payment for their performances, there is an obvious dichotomy between these models, who live in insecurity, and the situation of those whom they are supposed to represent: privileged members of the economic elite in Calais. In fact, recent research has shown that the famous sacrifice by the Burghers of Calais was a fiction4 resulting from a hagiographic casting of the French national myth; given the updating of this episode in the context of generalized austerity that is affecting a number of Western countries, we may reflect on the real meaning of sacrifice and of the victims in an economic system that holds the lower classes and the poor in a state of permanent siege.

Finally, although Hannah had used a device formed of vertical screens – in order to render the verticality of the sculptures – placed in a circle for Les Bourgeois de Calais: Crated and Displaced, the deliberate decision made by him and Arcand to reprise this arrangement for The Burghers of Vancouver is particularly striking not only because this verticality contrasts with the usual orientation of movie and television screens, thus inscribing it in video art, but also because it singularly renders the genre of the portrait and the sensation produced by the commanding presence of Rodin’s works. In sum, the transition from the classic format associated with landscape and panorama to a more pictorial format is judicious: it utterly changes our relationship with the common representation and reproduction of these works and is instrumental to having the installation “function” with a public familiar with visiting the original bronzes.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the invention of cinema and beginning of democratization of the photographic press, contemporaneous with the work of Rodin, also coincided with the serial production of originals through which Rodin quickly achieved international distribution and visibility. There is much more to say about how the video installation inscribes this sculpture and the tableau vivant that reproduces it in a relationship with time and space that refers to the intermingled origins of photography and cinema, in the desire to both represent movement and reproduce artworks as such. Hannah’s dissertation is eloquent on the subject; for those who want to know more, it is worth an attentive reading.

To conclude, it is important to mention that this article was written without direct experience with The Burghers of Vancouver: in a curious distancing and no less curious mise en abîme, I undertook to imagine, through this essay, the video reproduction of a video installation, which, in turn, reproduces, through a tableau vivant, an original sculpture based on a myth and reproduced in twelve copies from a mould from which it is no longer possible to make further copies . . .

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Adad Hannah, Extending the Instantaneous: Pose, Performance, Duration, and the Construction of the Photographic Image from Muybridge to the Present Day. Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University, Montreal, 2013, spectrum. library.concordia.ca/977197/.

3 The last legal casting – the series was limited to twelve copies under French law – was made in 1995 for the Samsung Foundation of Culture in Seoul. This final bronze gave Hannah the impetus to create a first variation on the subject, called Les Bourgeois de Séoul (2006). In this work, motorized messengers had been asked to take the exact pose of the original sculpture in their work uniforms. The installation created a parallel between two sequence shots, presented on two screens placed side by side, in which the camera made a complete circumvolution – one around the sculpture, the other around the “tableau vivant.”

4 Jean-Marie Moeglin, Les bourgeois de Calais: essai sur un mythe historique (Paris: Albin Michel, 2002).

Sébastien Hudon, director of La Bande Vidéo, is an author and independent curator. He has worked in various museums, including the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in positions related to the acquisition and documentation of photographs. As a curator, he has organized two exhibitions at Maison Hamel-Bruneau, in Quebec City: Concerto en bleu majeur and Photographes rebelles à l’époque de la Grande Noirceur (1937-1961).

Adad Hannah est né à New York en 1971. Il partage aujourd’hui son temps entre Montréal et Vancouver. Adad Hannah s’intéresse à la manière dont le corps occupe l’espace, à la notion de tableau vivant et, plus généralement, à la relation entre photographie, vidéo, sculpture et performance. Ses œuvres font, entre autres, partie de la collection du Musée des beaux-arts du Canada (Ottawa), du Museo Tamayo (Mexico), du Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art (Séoul), du San Antonio Museum of Art, du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal et du Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. Adad Hannah est représenté par Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain (Montréal) et Equinox Gallery (Vancouver).

adadhannah.com

Denys Arcand was born in Deschambault-Grondines, in 1941. He has directed twenty-three feature films, including The Decline of the American Empire (The Director’s Fortnight, Cannes Film Festival 1986, nominated for an Academy Award), Jesus of Montréal (Jury Grand Prize and the Ecumenical Prize, Cannes Film Festival 1989), The Barbarian Invasions (Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film; César Awards for Best Film, Best Director, and Best Screenplay; and several Canadian Jutra [Quebec] and Genie Awards in 2004), Days of Darkness (Out of Competition Official Selection, Cannes Film Festival 2007), and An Eye for Beauty (Toronto International Film Festival 2014).