“Mother and teacher mine, my sad and spacious Spain”: this is how the poet, Blas de Otero described his country’s vast geography and serial suffering under the double yoke of monarchy and religion, and then under fascism. Those regimes have ended, but Spain’s economic trauma has returned, a condition reflected in the organization of its Madrid-based photography festival, PHotoEspaña. Since it began in 1998, under the directorship of the private cultural organization La Fabrica, combined public and private sponsorship has supported the festival’s steady growth. Major divestments in government support, however, have inspired creative strategies by its current director, Claude Bussac. Rather than having a crippling effect, the increased private sponsorship and greater collaboration with institutions and regions across, and even outside of, Spain seem to have only expanded the festival. Also lightening its financial footprint was a shift from its usual thematic focus, engaging international curators and artists, to a focus on Spanish photography. The critical and creative energy harnessed by the festival this year, with its 440 artists, across 110 exhibitions in three countries, showed a Spain that is very much alive and struggling on.

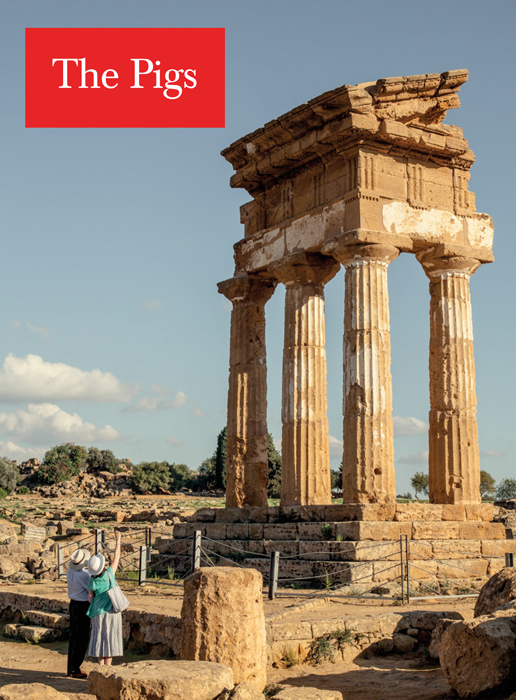

The festival’s focus this year on Spanish photography provides a timely opportunity for reflection on the country’s past and future. It may also be an assertion of national identity in the face of criticism from its European Union neighbours. Receiving an honourable mention from among the hundred international publications displayed in Best Photobooks of the Year exhibition was Carlos Spottorno’s The Pigs, a satirical mock-up of the British financial magazine The Economist. The acronym PIGS was used by neoliberal economists to designate the debt-laden EU nations of Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain. Spottorno’s documentary photographs in the book illustrate the offending negative stereotypes of backwardness, poverty, and disorder.

Although Spain’s examination of its own photographic history is not new, never before has it been so extensive. The Biblioteca Nacional de España drew from its archive for the exhibition Photography in Spain, 1850–1870. Spain’s late modernization is revealed through its photographic history. The earliest photographic processes and genres were introduced by foreigners, such as Charles Clifford, who produced images of exotic Spain for foreign consumption. Alongside Clifford’s images were works by Spanish photographers who later established portrait studios and documented public works.

Art photography in Spain was long dominated by pictorialism and the use of painterly pigmentation techniques. Both were well suited for the idealized, agrarian, nationalist images preferred by the ruling elites over images of the harsh realities under the monarchy, and then Franco. The Museo del Romanticismo exhibited Joan Vilatobà’s tonally rich carbon prints from the early twentieth century. Vilatobà’s sensitive attention to light is a common feature in Spanish photography, but his overwrought, melodramatic allegorical scenes are anachronistic versions of earlier Victorian pictorialism – far from Spanish culture of the time, which had begun to modernize.

José Ortiz Echagüe was celebrated throughout the Franco regime for his nationalistic photographic surveys of Spanish landscapes and popular types. Shown at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando was a collection of Echagüe’s earlier work, mostly from 1911, when he was serving as aircraft photographer in the Spanish war in Morocco. His soft, handworked Fresson prints are aestheticized documents of the inhabitants of the Rif. Impressionistic glimpses of men and women enveloped in voluminous robes that protected against wind and, in the case of the women, male eyes, express the exotic allure that these subjects held for their colonizers. In the highly aesthetic, atmospheric images that Echagüe made on his return visit in the 1960s, his subjects appear timeless within their now-changed environment.

During the brief respite between 1932 and 1936, the pre-Civil War Republican government enthusiastically courted foreign influence, the effects of which were seen in Espacio Fundación Telefónica’s extensive display of Antoni Arissa’s work. Arissa’s early-twentieth-century images of idealized agrarian workers outside of Barcelona are unique interpretations of the pictorialist style. His later work, made in the 1930s, portrays urban and industrial subjects presented through modernist aesthetics. Their radical, geometric perspectives are evocations of New Vision practices by Moholy-Nagy, Rodchenko, and Kertész.

Engaging very differently with European avant-garde influences was Josep Renau who, during the Republican period, made political poster art. In the colourful photomontage series American Way of Life, made when Renau was in Mexico, the exiled communist turned a searing eye not on the Nazi regime, as had his precursor, John Heartfield, but on the emerging superpower, the United States. Renau’s prescient, satirical critiques, still relevant today, slam that government’s militarism, racism, cold war imperialism, sexist commercialism, and alliances with corporate power.

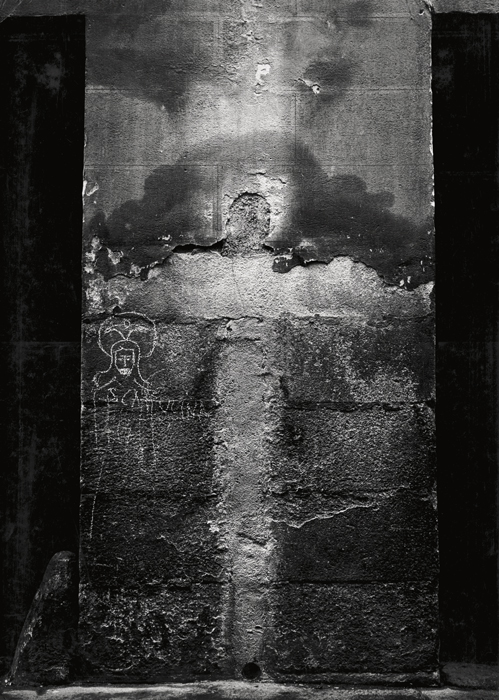

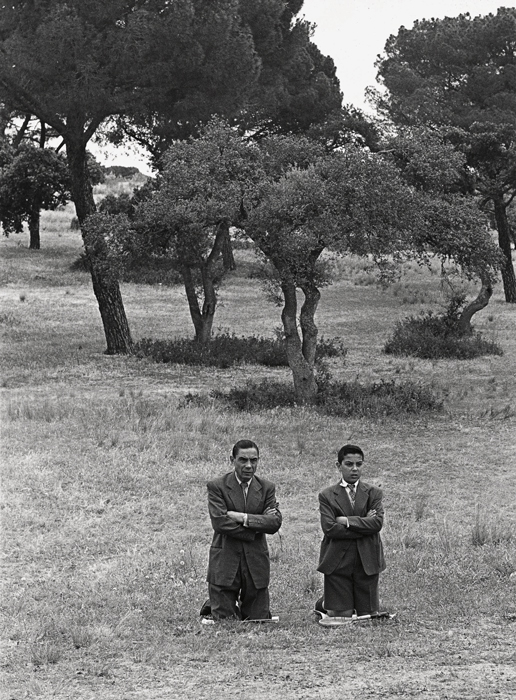

The heart of PHotoEspaña is usually found at the cultural centre Círculo de Bella Arte, as it was again this year. One of the three exhibitions at that venue was La Palangana, titled after the Madrid photography collective formed in 1959. Inspired by the humanist documentary style exemplified by W. Eugene Smith’s photo-essay Spanish Village, the collective’s goal was to break the grip of outdated pictorialism. Its members’ forays outside of Madrid resulted in deep-toned, realist images that showed the harsh light and life of rural Spain. Apart from occasional lighter moments, in the mode of Cartier-Bresson, it seems that only the children, as seen in Leonardo Cantero’s grainy La Dehesa del Hoyo (1959), escape the oppressive forces of hardscrabble poverty.

Since Franco’s death in 1975, Spanish photography has flourished, influenced by its own unique history and international trends. The exhibition curated by artist Joan Fontcuberta, Fotografía 2.0, brought together twenty contemporary Spanish artists in a serious investigation into the much-discussed but little-understood digital revolution – the contradictions of freedom and control, of access to information and surveillance, inherent in our digital terrain. Absent are the usual idealizing claims for a democratic Internet; the artists show instead its darker underside, as a new means for social control. Many of the artists in this show use “post-photographic” recycled Internet imagery to examine these issues.

Darius Koehli’s Jail and Mugshots (2013) critiques the Arizona prison officials who posted mug shots and webcam footage of suspected criminals in custody on the Internet for the purpose of crime deterrence. Koehli’s video collage of those mug shots is organized by offence – theft, drug charges, and so on. The disturbed faces are overlaid in quick succession, creating a Galton-esque composite of distress. The problem, explicit here and elsewhere in the exhibition, is that despite the critical value of such works, they perpetuate the power imbalances between those who make, look at, and are subjects of photographs.

Similar tension is expressed by Reinaldo Loureiro, who accessed photographic images of illegal African immigrants found by border police at Melilla. On top of a large colour photograph that shows a man hiding beneath car panels is set a monitor that flips through images of unfortunates that were similarly captured by guards, cameras, and, finally, gallery viewers (Farhana, 2010, ongoing).

Humans are not alone in our subjection to image capture – our anthropocene privilege allows visual access to the natural world as well. Albert Gusi’s collection of thirty-three digital images were taken by a camera designed to track bear populations reintroduced into the Spanish Pyrenees. The images – rejected from the study since no bears participated – display the startled expressions and flash-obliterated eyes of “wild” deer and hares, trapped by an omnivorous camera gaze, sadly reflecting our human power (Intruders, 2014).

Delightfully switching the surveillance gaze onto the invisibly powerful is Daniel Mayrit’s piece You Haven’t Seen Their Faces (2014). Critiquing the London police force’s call to the public to identify individuals captured by surveillance cameras during the 2011 riots, one hundred headshots of London’s most powerful (responsible for the crisis that triggered the riot) were manipulated to mimic low-quality surveillance capture.

The arrangement of Fosi Vegue’s digitally noisy colour photographs inside a darkened gallery space was an exercise in voyeurism. Cropped bits of bodies are engaged in sexual activity – a shoulder arched in exertion, fingers resting on a woman’s head, a hand grasping flesh. Our visual access to these heated moments, obstructed by window frames or in post-production, is narrow, making them all the more captivating. Vegue’s images of ‘private’ transactions between prostitutes and partners captured across an open courtyard reiterate the voyeuristic impulse so active today (XYXX, 2013).

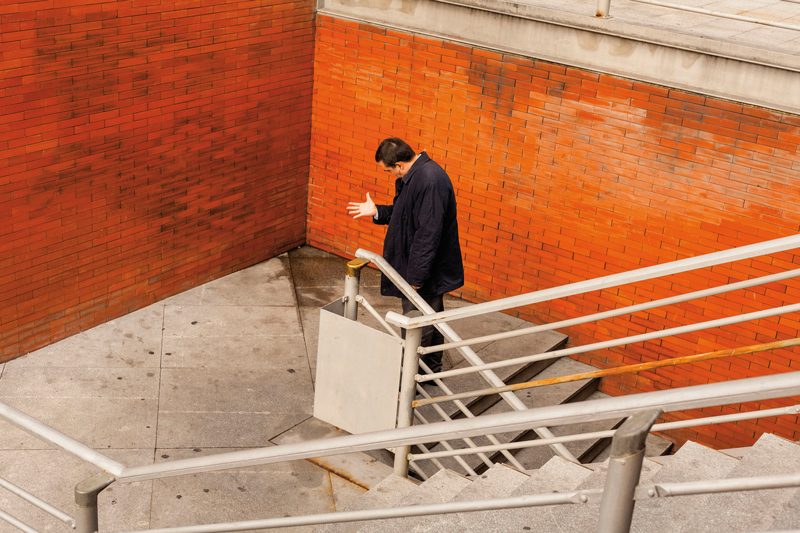

The most current Spanish photographic art was on view in P2P: Contemporary Practice in Spanish Photography. Óscar Monzón’s video RPR (2014) is documentary aerial footage of silhouetted figures moving across a plaza under midday sun. Their movements, as they walk alone or encounter others, become a mesmerizing choreography when set to synthetic sound, extending Muybridge’s animal locomotion studies to social ethnological patterns. David Hornillos’s striking colour photographs (Mediodía, 2001–14) document banal non-events against the vivid orange tile walls of Madrid’s Atocha train station, giving brilliant treatment, under a noonday sun, to the urban homelessness and detritus that is usually disregarded and disparaged. Besides picturing the qualities of Spanish light, some artists explored light as a basis for photography. Miguel Ángel Tornero looks to photographic pre-history, when photosensitive reactions to light, such as the fading of dyed fabrics and Niépce’s hardened asphalt, inspired the invention of photography. Tornero used materials such as used foam in his installation Photophobia, to present photography as “an active protagonist rather than a mere container for an image.”

Part of the fun of PHotoEspaña was finding its venues around Madrid. Matadero, the vast meat processing facility turned cultural centre, hosted two exhibitions. Similar to Tornero’s interest in photographic essences, Sara Ramo, in her installation Penumbra (2014), playfully evoked primary photographic processes – the construction (literally) of visual illusion. Visitors were led to seats through a darkened space by flashlight-carrying ushers. Slowly, as our eyes became accustomed to the darkness, a landscape began to take shape before us. Like the action of light on photographic film, an impression gradually settled on our retinas. And what were these vistas made from? Old materials and props recycled from previous Matadero events.

In All the things that are not there (1985), Teresa Solar Abboud tracks connections between the photographic and military innovations of MIT scientist Harold Edgerton. The video shows Abboud road-tripping across the United States from Massachusetts, where Edgerton developed the high-speed photographic strobe and underwater sonar units for military use, to the Nevada Test Site, where Edgerton’s company, EG&G, as a national defence contractor, provided high-speed triggers and photographic imaging of atomic bomb tests, and finally to his secret California studio, where the resulting visual data were analyzed. Punctuating Abboud’s visits to the mostly restricted sites were poetic long shots of figures swimming under rippled waters and meditations on the more positive knowledge produced through Edgerton’s image technologies: how bats navigate in space with sonar and how hummingbirds fly backward. This attention to the dialectically positive and negative roles of photography echoes Echagüe’s contradictory military and photographic work in northern Morocco.

Apart from the Spanish work represented in the festival’s official section, Festival Off and Open Photo provided many opportunities to see international work in private and public venues, both in and outside of Madrid. An extensive collection of Man Ray’s works, both vintage and reproductions from original negatives – including many of his well-known works – was presented by Mondo Galería. Elba Benítez Gallery presented Chantal Akerman’s video and photographic installation Maniac Shadows (2013). Outside of Madrid, Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s work was shown in Alcobendas, and Pierre Gonnord’s powerful portraits of Sevillian gypsies were shown in Almería. Spanish photographers were also shown outside of Spanish borders with Ricky Dávila’s exhibition Ibérica, in London, and Chema Madoz’s exhibition Ángulo de reflexión was featured in Les Rencontres d’Arles.

Giving a glimpse of what to expect from PHotoEspaña next year, when the focus will shift to a region very close to Spain’s heart and history, Latin America, was the exhibition Latent Element: Ten Photographers from Latin America. Among the strongest works was Brazilian artist Marlos Bakker’s photographic series what are fish dreaming about? (2013). Bakker captured the faces of drivers in cars as they waited for the light to change, overlaid with reflections on the windshield glass, wrapped in the hazy blue tones of their own reveries. The portraits by another Brazilian, Gustavo Lacerda (Albinos, 2009–13), are striking in their austere symmetry.

And so, PHotoEspaña survived, having taken lessons, perhaps, from Spain itself – sad, spacious, and stricken with light.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.