By Zoë Tousignant

Béla Ferenc Egyedi was born in 1913 in Esztergom, Hungary. He immigrated to Canada in 1951 and lived for many years in Montreal’s Milton-Park neighbourhood, at various addresses on Lorne Avenue and Durocher Street, near Milton Street. He was simultaneously a photographer, a printmaker, a poet, and a ceramicist. He died intestate at the age of sixty-nine, in 1982. As he had no relatives in Canada, all of his belongings – including his many artworks – were taken by the Public Curator of Quebec and sold at auction. The McCord Museum acquired his collection of photographs, which numbers several thousand.

I first came across the Béla Egyedi fonds on a spring day in 2013, and I was immediately intrigued and charmed (there is no other word for it) by the figure that emerged of the man himself.1 The fonds comprises a few dozen large-format exhibition prints, seventeen exhibition maquettes mounted on cardboard, a couple of binders containing prints and negatives, and seven letter-sized archival boxes filled to the brim with small and medium-sized photographs. Something that set this fonds apart from the others that I consulted that day was its inclusion of a remarkable, almost inordinate number of self-portraits.

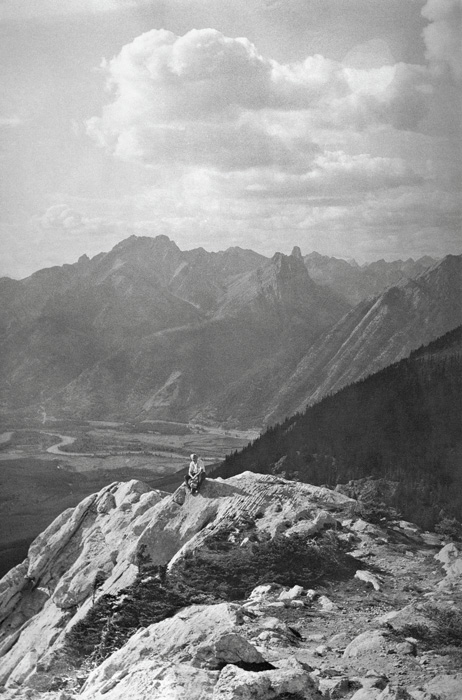

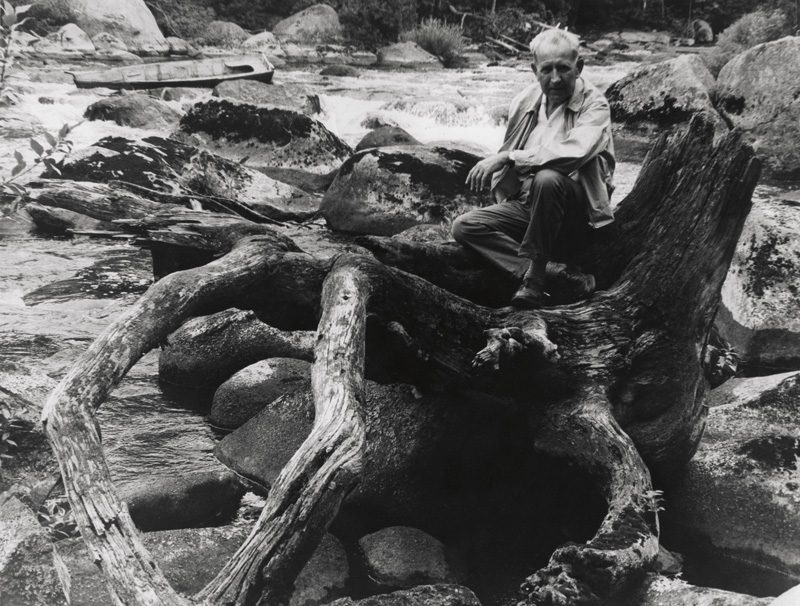

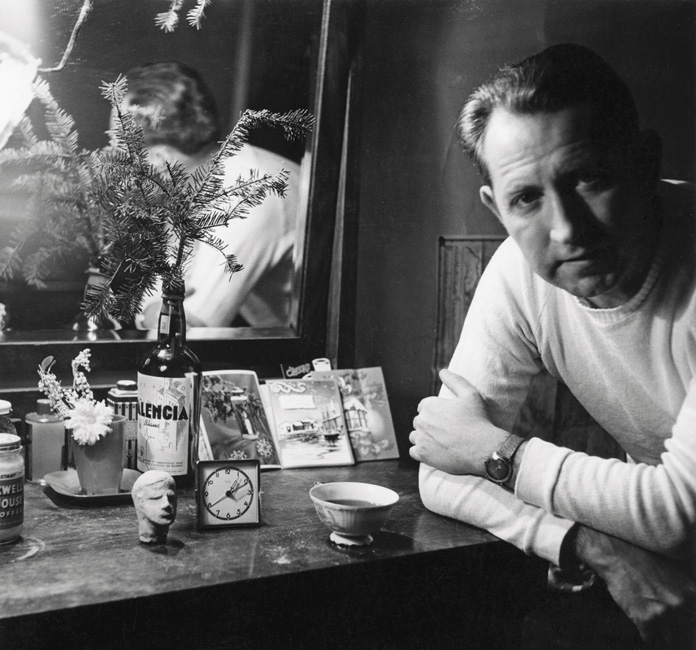

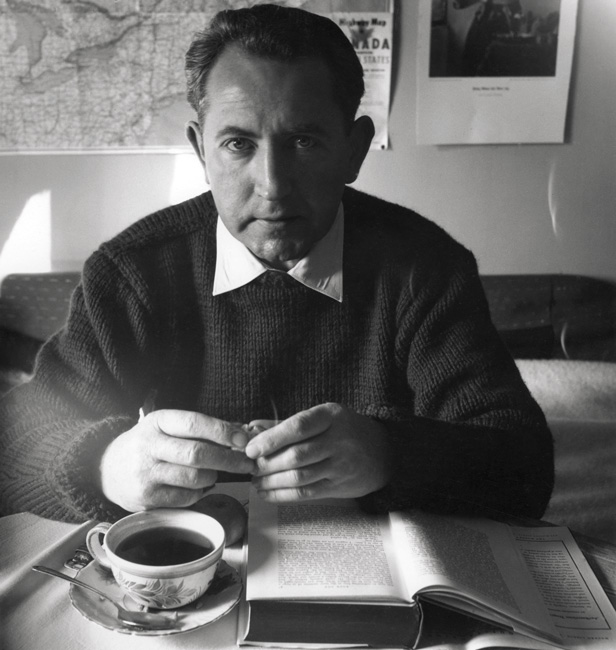

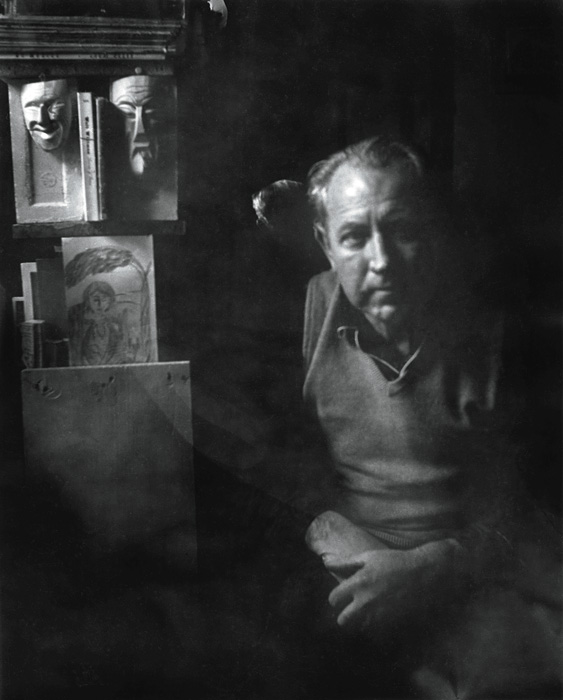

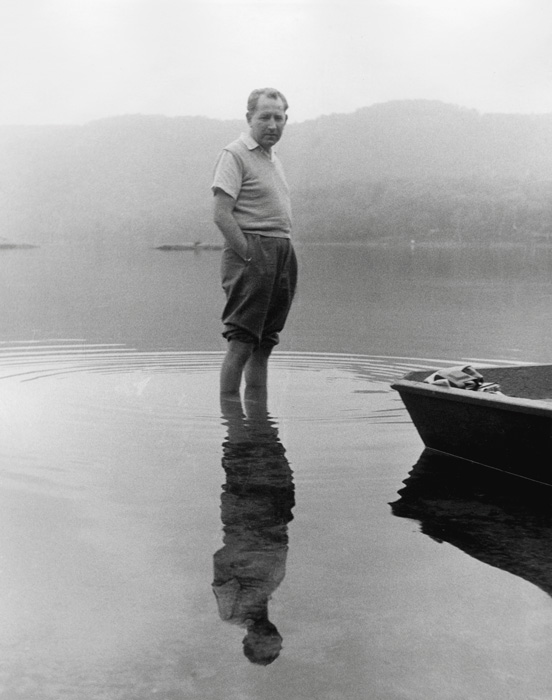

As I went through the seven archival boxes, which contain some enlargements made by Egyedi himself as well as hundreds of small prints developed by local photo labs, the constancy of self-portraiture in his work became abundantly clear. Save for a lone graduation photo that shows him as a young man in 1933, the portraits of Egyedi seem to begin in the years following the Second World War and continue throughout the rest of his life. They are quite often taken at home, where he can be seen posing beside a display of personal objects, but the majority of the portraits represent him in exterior settings, frequently in a landscape. With perhaps one or two exceptions, he is pictured alone.

The sheer repetition of his image in a variety of contexts and poses – his mug regularly staring straight into the camera – gives the impression that, for Egyedi, self-portraiture was a form of expression that was practised somewhat maniacally, yet was also exploited for its considerable performative potential. Although only a small portion of the total number were made into larger prints (some examples of which are reproduced here), self-portraiture was quite obviously a tool for self-affirmation, a way for him to state “I am here.” With always a dash of tongue-in-cheek humour and, I would add, a beautiful use of deep shadows, the photographer seems to have recorded his own image in order to symbolically carve out a place for himself in his country of adoption.

Why do people take self-portraits? What do they mean? Commonly seen as worrisome symptoms of narcissism, fundamentally they signify aloneness: we take a self-portrait because no one else is around to take our picture for us. They are also a means of exercising greater control over our image: rather than being at the mercy of someone else’s gaze, we can present ourselves to the outside world in a manner that pleases our self-perception. And they can be useful instruments of self-scrutiny: observing one’s image in varying poses, demeanours, settings, and times can simply be a way of learning more about oneself.

Self-portraiture has long been a prominent genre in the history of visual culture, and no less so in the history of photography, in which the earliest known examples, Hippolyte Bayard’s 1840 trio Le Noyé (Self-portrait as a drowned man), are captivating instances of playacting.2 The twentieth century has produced such influential photographic self-portraitists as Claude Cahun, Andy Warhol, and Cindy Sherman, all of whom have taken full advantage of the genre’s performative dimension. It is certainly nothing new, yet it is widely acknowledged that the self-portrait is more prevalent now than ever. This is the “age of the selfie,” an age in which narcissistic imagery has become normalized by flooding all available outlets of social media and by seeping – however self-consciously – into the “traditional” media of books, newspapers, and television.3 No longer the exclusive domain of fourteen-year-olds, the selfie (or, in French, l’égoportrait) has assumed an important place in the contemporary economy of photographic imagery.

There is no doubt that my interest in Egyedi’s images can be situated within and understood as an outcome of the genre’s current prominence. There is an attractive familiarity to his images, a contemporaneity made all the more compelling by the fact that the earliest date from over sixty years ago.

They are familiar, furthermore, because of their resemblance to another contemporary photographic development: the Vivian Maier phenomenon. Since about 2010, the world of photography has been taken by storm by the discovery of a massive body of work by the unknown and mysterious “nanny who took pictures.” Maier, who died in relative obscurity and poverty in 2009, actively practised photography for several decades while working as a governess for affluent families living mostly in the Chicago area. Never attempting to sell or disseminate her photographs, she nonetheless created an extensive documentary record of American street life from the 1950s to the 1990s. Her personal archive, which included thousands of negatives and rolls of undeveloped film, was bought at auction two years before her death by a handful of collectors who have since made it their mission to bring her work to international currency. Since 2010, several books, dozens of exhibitions, and two documentary films about Maier have been made.

Maier was undoubtedly a talented photographer, but a significant part of her attraction seems to be the mystery surrounding her life and the ambiguity of her motivations for photographing – or so it seems in the two documentary films about her, which take different methodological approaches to filling in the void. The tack taken in Finding Vivian Maier (2013), which was written, directed, and produced by Charlie Siskel and John Maloof (the latter is one of the principal owners of her work), is to conduct interviews with the various people who came into contact with Maier, including some of the children she cared for. Because of these people’s limited and often competing views of the photographer, the mystery is left intact – and even cultivated – in the film. Vivian Maier: Who Took Nanny’s Pictures (2013), which was directed by Jill Nicholls and produced by the BBC, takes a more archival approach by attempting to piece together elements of the puzzle through public documents, private letters, and some photographs.

The controversial – and theoretically interesting – aspect of the Vivian Maier phenomenon lies in the fact that the vast majority of the prints that have been sold and circulated on the international gallery circuit over the past few years were made posthumously, from negatives. Her body of work, which numbers over 150,000 images, has been undergoing a considerable editing process at the hands of its current rightful owners, and it is on the basis of this process that her photographs are being valued today. Joel Meyerowitz, who is interviewed as a specialist of street photography in both documentaries, summarizes the controversy when he asks concernedly, in the BBC film, “What kind of editors are they?” In other words, given how little is known about her own intention as a picture maker, who are they to decide what her photographic legacy will be?

Like Egyedi, Maier was an avid self-portraitist. One of the books published on her (and edited by Maloof) is dedicated to her self-portraits, and like Egyedi’s they are fascinating, not least because they encapsulate a paradox at the heart of the Vivian Maier phenomenon: her simultaneous presence and absence. Maier was, until her death, utterly absent from the history of photography, yet materially, in her own photographs, she is a ghostly, recurring presence. To date, Egyedi, too, has been entirely absent from the history of photography – even on a local scale. Yet in the archive, he is omnipresent.

Information about Béla Egyedi’s life and art can be gleaned from his photographs and from other documents in the fonds. The McCord’s collection contains a few of the exhibition posters that he designed and engraved himself. These reveal, for instance, that he exhibited his work at various Montreal locations in the 1970s and early 1980s, including Véhicule Art and Paragraph bookstore – and that he admired fellow Hungarian photographer André Kertész enough to dedicate an exhibition to him (a show titled Humor Foto). The fonds also contains some of Egyedi’s publications, which demonstrate that he regularly contributed poetry and graphic work to the Canadian literary journals Nebula and The Antigonish Review. Among the publications is a copy of his self-published book Haiku etc., a work of poetry and free prose that features a short autobiography.

From this autobiography, a clearer picture of the circumstances of Egyedi’s beginnings and immigration to Canada emerges. In his own idiosyncratic words, he was the “6th child to a ‘poor-but-honest’ painter (family-legend: his dream of becoming an artist . . . His ‘benjamin’ did just that (following in the footpath of his father’s dreams: faute de mieux) in a land where with his father’s vocation he’d have been a – succe$$$).”4 With characteristic dark humour and a keen playfulness, he recounts that he was just over six months old at the start of the First World War, which took his father away for the duration. His mother died of Spanish flu in 1919, after which his father remarried. In spite of a difficult home life, he excelled in school and had begun graduate studies in French and German literature and linguistics when the Second World War broke out, leading him to acquire a more “practical” degree in journalism. Having worked for the Hungarian News Agency and exempted from military service, Egyedi was “liberated” by Russian troops during the 1944 Siege of Budapest and interned as a prisoner of war. In 1948 he fled from Hungary and made it to Paris, where he remained until 1951, when he immigrated with refugee status to Canada. While based primarily in Montreal, he made several trips as an itinerant worker to the western and northern regions of Canada.

After his death in 1982, a one-page tribute to Egyedi was published in The Antigonish Review. It states that he “did not receive the recognition which his talents should have brought him. . . . Our contact with béla has made us more conscious of the great creative contribution made to Canadian culture by the many thousands of immigrants who have fled the European continent in the last 40–50 years. Many have achieved success and recognition in various fields here. Many others, arriving in their thirties or forties, have not been so lucky, and have labored in obscurity.”5

Recognized for his contribution to the literary field, he has also been acknowledged as a “mail artist” by a current website devoted to the genre.6 While it is unclear what type of art he sent out, his personal papers disclose a veritable obsession with receiving mail, and, frustrated with the unreliability of the Canadian postal system, he even opened an additional P.O. box. In a stroke of fate that might have appealed to his particular sense of humour, he died after being hit by a postal truck.

Yet Egyedi’s photographic archive, acquired by the McCord mere months after his death, has been effectively dormant for over thirty years (the images reproduced here were catalogued and scanned for the purpose of this essay). The fact is, he is not alone: there are many other fonds similar to his at the McCord – and in the thousands of other photographic collections scattered across the world. So, what shall we do with these photographs?

In my view, the answer is not to try to fit cases like Egyedi into the conventional frame of the history of photography – to try to transform him, through shrewd editing and reprinting, into a “master of photography,” as has been done with Vivian Maier. For there is a reason that Egyedi did not fit into the conventional frame to begin with: he was different.

The vernacular turn in photographic studies has opened the floodgates to an appreciation of a whole new area of production: snapshots, cartes-de-visite, postcards, and other photographic ephemera are now frequently discussed by historians – and used as source material by contemporary artists. With this new appreciation, unknown or forgotten photographers like Egyedi and Maier will increasingly be coming out of the woodwork. This is a good thing, but this appreciation has to be accompanied by an equally new conception of the photographer. Egyedi is an interesting case because he had what I could emphatically call a photographic practice. Seemingly unconcerned with fitting into the system of limited-edition museum-quality prints, he nonetheless used photography to explore the manifestations of his own subjectivity. Repeatedly, he asks us to confront this subjectivity; he demands, from the depths of the archive, that we finally see him.

2 See Geoffrey Batchen’s discussion of Bayard’s photographs in Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997), 157–73.

3 Reality television star Kim Kardashian will be releasing Selfish, a book devoted to her selfies published by Rizzoli, in 2015; the actor James Franco published an opinion piece called “The Meanings of the Selfie” in The New York Times (December 29, 2013); and the television show Selfie, a contemporary take on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, premiered in September 2014.

4 Béla F. Egyedi, Haiku etc. (Montreal: self-published, 1980), 25.

5 George Sanderson, “Tribute to Béla Egyedi,” The Antigonish Review 51 (Autumn 1982): 5.

6 See “The Dead Mailartists Club,” “Keith Bates – Mail Art,” http://keithbates.co.uk/cameraderie.html (accessed September 26, 2014).

Zoë Tousignant is a photography historian and independent curator specializing in Canadian photography. She holds a PhD in art history from Concordia University and an MA in museum studies from the University of Leeds. Her research interests revolve around the dissemination of photographic culture in Canada, both historically and in the present.