[Spring 2010]

By Martha Langford

A constellation of events has shone light on the photographic oeuvre and life in photography of Gabor Szilasi. Its first manifestation was in 2008, a the- matic exhibition, Famille, originally organized for the McClure Gallery by Hedwidge Asselin. This show is now on a two-year tour of Montreal, under the aegis of the Conseil des arts de Montréal. In the summer of 2009, Szilasi’s sense of place was explored in Le Québec par cœur, presented at the Galerie Méridien Versailles. Anticipation was growing for a full retrospective, Gabor Szilasi: L’éloquence du quotidien/The Eloquence of the Everyday, organized by David Harris for the Musée d’art de Joliette and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. No one who experienced these exhibitions, and the outpouring of admiration that accompanied them, could have been surprised when Gabor Szilasi won the Prix Paul-Émile- Borduas 2009, one of the prestigious lifetime achievement awards grouped under the Prix du Québec.

To celebrate this moment in Szilasi’s life and his community’s history – and we should – means something more than raising a glass. Or rather, that is precisely what we should do, following the example of Harris, who recently spoke about the exhilarating, sometimes bewildering experience of staring through the loupe at Szilasi’s contact sheets. This process, which can be sampled in the catalogue, no doubt enriched the Szilasi retrospective immeasurably and also suggests how much more could be found in his archives. Past, present, and future events make this constellation radiate, but the brilliance at the core is nothing more, nothing less, than photography.

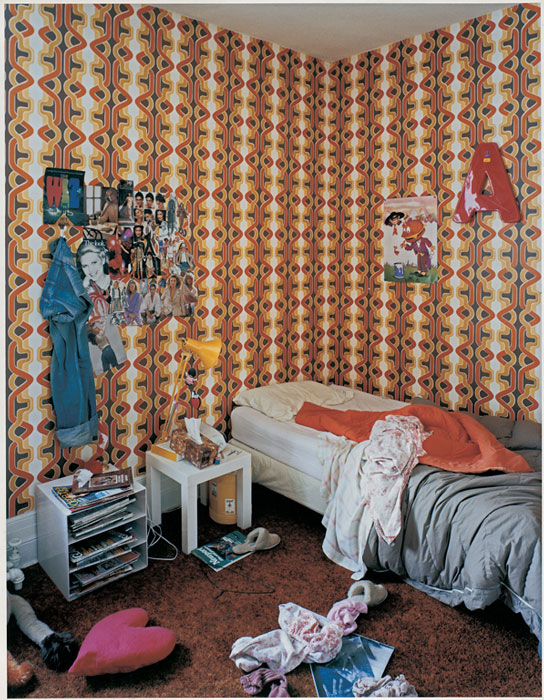

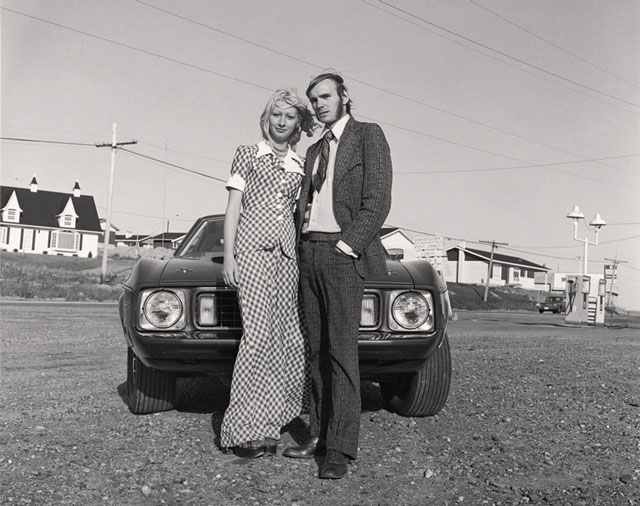

Born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1928, Gabor Szilasi has been making photographs since his mid-twenties, his first images predating his escape from Communist Hungary and immigration to Canada in 1957. He carried with him an appreciation for the European style of photographic reportage, as well as an immense curiosity about his new country, especially its Francophone culture, into which he threw himself on arrival. Without recapitulating every stage of his career, it seems important to remember that this esteemed teacher started out as a working photographer at the Office du film du Québec, where he had both motive and opportunity to get to know the province. And so he did, in all its facets, documenting the vestiges of its rural, Catholic foundations, as well as Montreal’s urbane, sometimes-amoral confidence as the motor of Canada’s modernity. Such contradictions are not compartmentalized in Szilasi’s work, but embraced. This is never truer than in his environmental portraits and empty interiors, in which the lure of the image is an incongruous temporality or element that nevertheless fits. Two photographs of the Yergeau house, Rollet, Témiscamingue, taken in July 1977, are exemplary. The living room of the house celebrates a perpetual Christmas, and not sadly as a tarnished ideal, but as something cherished and maintained, in a perpetual present. The bedroom is equally vibrant. Indeed, its visual cacophony beggars description, its walls and ceilings papered with pornography and religious art, including (reflected in a mirror), the portrait of a priest. In Szilasi’s Quebec of the 1970s, a wedding waltz is being danced under an acoustic-tile ceiling; televisions illuminate domestic shrines; cowboys are disciplining horses and each other at the rodeo.

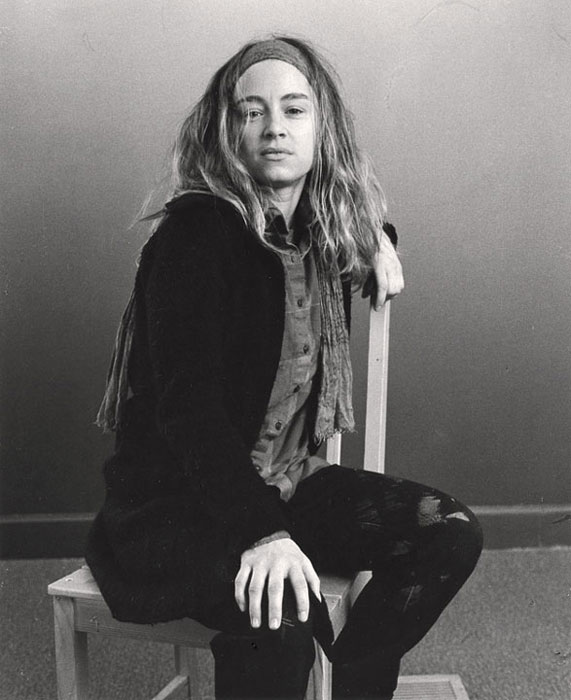

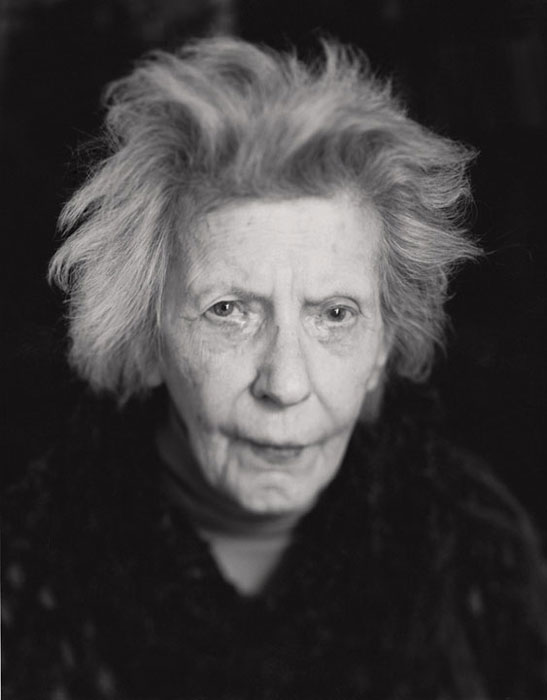

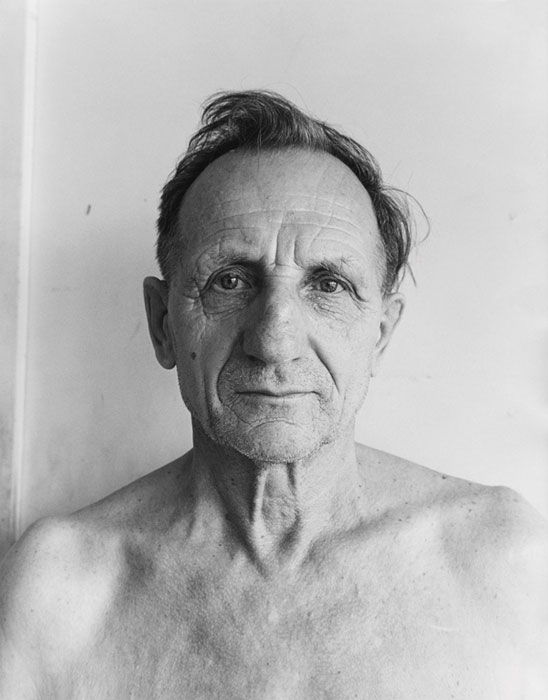

His candid portraits of single figures tend to catch them in repose, so that the things around them form thoughts, memories, unfulfilled ambitions

Back in town – and the town is unmistakably Montreal – Szilasi, patient and alert to change, becomes the photographer of record who captures the architecture and graphic expression of commerce, confluence, planning, and its antithesis, capitalist sprawl. Szilasi has an eye for the picturesque, though he defines it rather singularly, as shown in his view of the meeting façades of the Rossy and Woodhouse stores on St. Catherine Street East. On this shopping street, he does not close in tight on the window displays, as Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, or Tom Gibson might have done, but pulls way back to photograph the full elevation. This decision transforms the windows of the upper storeys into an astonishing study of greys. There are architectural photographers who specialize in the immutable, others who underscore the fugitive aspects of the built environment. Szilasi does both in the same picture, achieving coherence because he has found the right place to set up his camera and knows why he is there, which is to make a certain kind of picture. Szilasi’s contributions in this area are especially well conveyed by the choices and arrangements that Harris has made in the gallery. Szilasi’s remarkable panoramas – he is unexcelled at this form – need to be appreciated as prints, but even their layout in the catalogue tells us something about his prodigious skills at organizing the complexities of urban space, the strategies that he has refined, and the variations that he has developed over time.

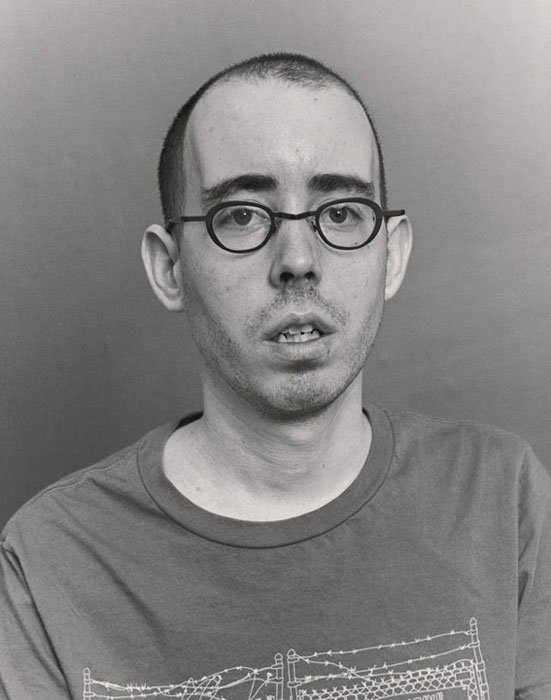

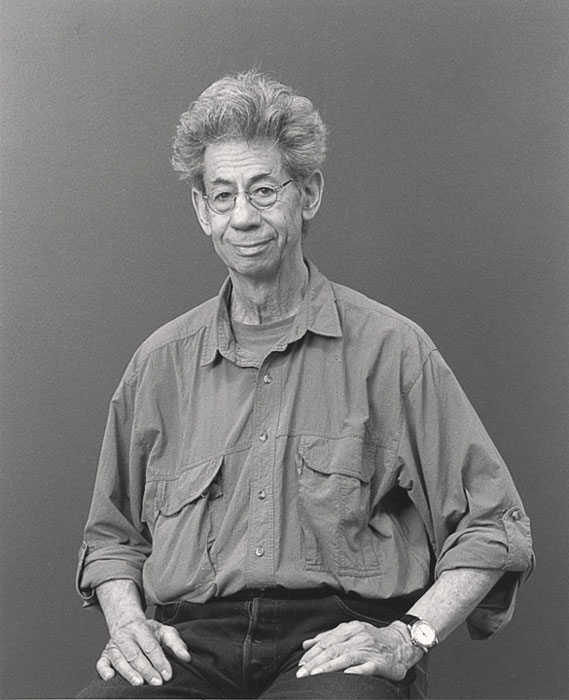

A retrospective is all about time, the small slice of the longue durée that even fifty-plus years of photography represents. Szilasi’s approach to photographic portraiture expresses this throat-tightening realization. His candid portraits of single figures tend to catch them in repose, so that the things around them form thoughts, memories, unfulfilled ambitions; lives arrested by his camera seep into the spectator’s imagination in this suggestive way. Considering the distinctiveness of his portraits – and there is scope, for some of his subjects, especially cultural personalities, have been much photographed by others – one is struck by the absence of any authorial claims on the figure. When the subject stares into the camera, as Marion Wagschal and Serge Clément do in their portraits, there is a spirit of cooperation that is truly “consensual” – somehow, Szilasi has communicated exactly what he is doing, thereby readying the subject to do his or her part. The whole thing feels very down-to-earth and absolutely devoid of any kind of grandstanding, on either side of the camera. To speculate on how Szilasi achieves this, one might venture “practice,” in the broad sense of having made all kinds of studies of the human face and body, both candid and posed, so that his presence before the subject is both impressive (a portrait is an occasion) and natural (“be yourself”). For the sitters, such encounters were nevertheless unforgettable, as came through at the opening of Szilasi’s retrospective, where one could observe some of the subjects easing up on their younger selves. So it was with sculptor Robert Murray, pictured in his Westmount home in April, 1969, fully absorbed in playing the bass, while his cat relates flirtatiously to the photog- rapher. “What happened to the cat?” I asked Murray, as we stood before the portrait. “He ran away.”

So many of the people pictured in Szilasi’s por- traits seem to have run away. How else could the irrepressible Guido Molinari no longer be on the scene, preening for Judith Terry? Where are Yves Gaucher and Sam Tata – they should have been at Gabor’s opening, for he was always at theirs, building his enormous, still largely untapped, archive of the Montreal art scene. His family came to Joliette, of course: his nuclear Famille and his extended family of photographers, curators, and citizens. Szilasi’s production touches people who know nothing of the art world, and comforts those who know too much. The sweep of this extraordinary photographer’s panoramic vision is almost overwhelming: from his views of Hungary in turmoil to the streetscapes, interiors, and portraits of its endurance; from country to city in Quebec, places bound up in their opposite’s rites and ambitions; from the heritage sites that photography preserves to the homes and galleries where photographic souvenirs, clippings, posters, and vintage prints are displayed; from the rigour of black and white photography to the kitschy explosion of colour; from the plucked-from-the-crowd beauty of a girl with a flower to the penetrating gaze (well known to the photographer) of Doreen Lindsay. Almost overwhelming, for this great life in photography is now coming clear to us in explanation and celebration, a telling that leaves room for the pictures yet to be discovered, yet to be made, by Gabor Szilasi.

One of Quebec’s best-known photographers, Gabor Szilasi began his career at the Office du film du Québec in 1959. His pictures were shown for the first time in 1967, and since then he has had countless exhibitions. His work is collected by numerous recognized institutions throughout Canada. A professor at Cégep du Vieux-Montréal until 1980, and then at Concordia University until 1995, he has been invited to give seminars on photography elsewhere in Canada, in the United States, and in Europe. Gabor Szilasi is represented by the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto and Art 45 in Montreal.

Martha Langford is the author of Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums (2001) and Scissors, Paper, Stone: Expressions of Memory in Photographic Art (2007), both published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. She is an associate professor and Concordia University Research Chair in Art History.