[March 13, 2024]

By Michel Hardy-Vallée

When you land in a new city, or a new neighbourhood, asking for directions may sometimes garner pearls like this one: “Turn left after the old Perrette corner store, the one they tore down.” The memory of places is much more deeply grounded than are buildings, whose existence obeys the rationale of capitalism more than that of residents’ lives. Three Montreal neighbourhoods – the Red Light District, the Faubourg à m’lasse, and Goose Village – were levelled by the city between the late 1950s and the early 1970s, and their disappearance formed the background for citizen protests against unbridled development, such as the one in the Milton-Parc district.

Goose Village, Marisa Portolese, Montreal, self-published, 2023, 229 pages, 25 x 23 cm, softcover, digitally printed

Although the Red Light District (downtown) symbolically endured as ground zero for night life and the Faubourg à m’lasse (in the east) is remembered for having been sacrificed on the altar of construction of the Radio-Canada/CBC highrise – now obsolete – Goose Village (in the west) was not graced with this second act in the collective memory. Even historical markers, such as the one Parks Canada put up there at one point, have been destroyed. Because her parents lived in this enclave near the Victoria Bridge, in the Pointe-Saint-Charles neighbourhood, Marisa Portolese here probes archives, places, and people in an approach that is at first autobiographical and then becomes historical. As she never lived there, she works from the perspective of someone trying to understand the demolition of habitus, as well as the mental levelling and the steamroller of forgetting that afflict her own family and extend to the immediate community and then to society as a whole.

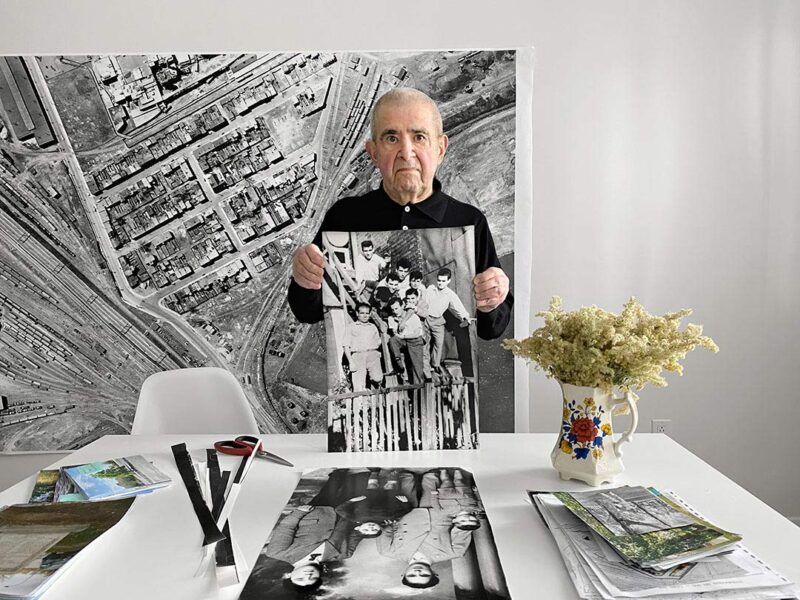

Portolese’s book Goose Village is based on meticulous research combining archival documents, oral history, and urban studies with her own work as a portraitist. As a researcher, she credits the exhibition Quartiers disparus (2011–13) at the Centre d’histoire de Montréal (today MEM) with making her decide to pursue her project, but her intention – to understand what Goose Village was, how people lived there, and what remains of it – had been simmering for a long time. She worked as a photographer, in continuity with her projects such as Belle de jour (2002) and In the Studio with Notman (2018). Transporting her studio techniques to the sites of the vanished village, revisiting and manipulating images produced by the municipal administration, she tries by various means to conjure a way of life that has gone up in smoke. From her research, we note that she has decoded, with the assistance of Gilles Lauzon and Denis Tremblay, the numbering system used by the city to identify photographs of the places to be demolished. She draws from them a complete panorama of one street that has disappeared, which might be subtitled, in tribute to Ed Ruscha, as Every Building on Forfar St. North.

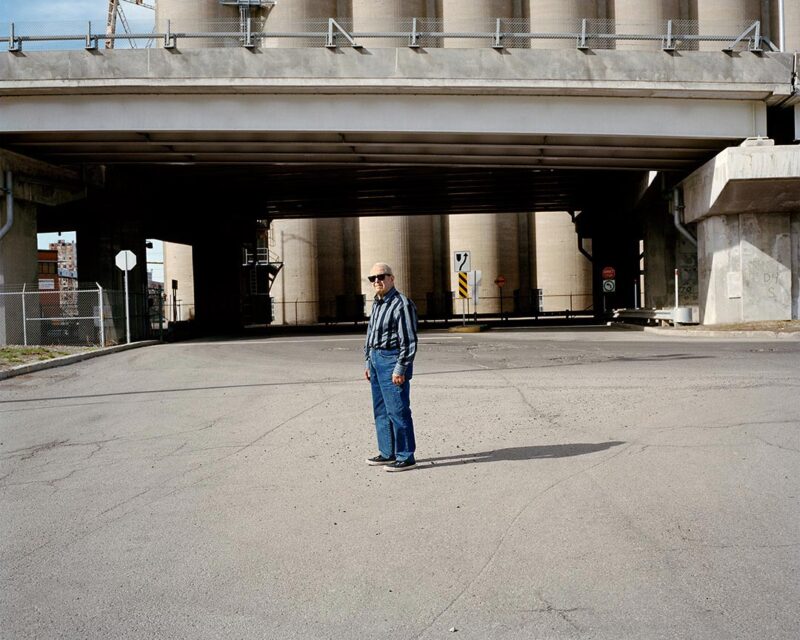

Careful study of the iconographic archives also led Portolese to attempt a systematic analysis of wallpaper so she could connect poorly documented images. From this ultimately fruitless effort, she nonetheless drew two striking still lifes: she printed the wallpaper motif at scale on large sheets of paper and stuck them on a wall, creating an installation that was a virtual version of a disappeared setting. Finally, by visiting the deserted parking lots, empty lots, and tangled undergrowth that remained of the neighbourhood with her parents, she produced a series of landscapes and portraits steeped in topographic absurdity and memory dispossession. As Italian immigrants, Portolese’s parents left much behind them, and the source of their own rootedness has also been erased.

All three “disappeared neighbourhoods” of Montreal were working-class districts into which waves of immigrants from Ukraine, Italy, Ireland and Poland moved, rubbing elbows with French Canadian populations. My mother grew up at the edge of the Faubourg à m’lasse, two streets from the St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian church, but she told me that at that time cultural communities were distanced by mistrust. Now more than ever, it is possible to decompartmentalize collective memory, and art allows such interventions to occur. Portolese’s visual intelligence in this project is worth a second act. The book gives an exhaustive description of her approach, but the sheer volume of text pushes the images toward the margins, and the commentary by curator Vincent Bonin sometimes repeats Portolese’s. We can understand the imperatives of research funding that explain the finished product, but one would also hope that a new, more ambitious version of the book will draw its affect from the calm, poignant intensity with which Portolese was able to put this social catastrophe into images. Translated by Käthe Roth

Michel Hardy-Vallée is a historian of photography, independent curator, and Visiting Scholar at the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University. His research is concerned with photobooks, visual narration, interdisciplinary practices, and archives, in the contexts of Quebec and Canada. He is currently working on a monograph about John Max.