[February 20, 2024]

By Laurie Milner

Moyra Davey’s book The Shabbiness of Beauty (2021) originates in and expands on an exhibition that she curated of her own work and the late Peter Hujar’s.1 It can be viewed as the continuation of an aesthetic and conceptual project that Davey has been engaged with for two decades: in complex combinations of images and texts, she explores similarities and resonances between the lives and works of a pantheon of modern photographers, filmmakers, and writers – many of them queer and many with lives tragically cut short – and her own. But it also marks shifts. In this project, Davey is careful not to construct parallels between her life and Hujar’s, choosing instead to distinguish between their respective modern and post-modern orientations.2 And, for the first time in a publication, she presents visual works apart from, rather than integrated into, her essayistic writing. This untangling of the visual from the textual gives space to and invites a more focused experience of the images, individually and in relation to one another.

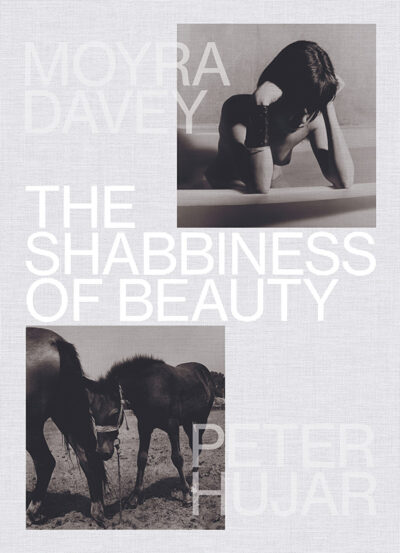

The Shabbiness of Beauty, Moyra Davey & Peter Hujar, London, MACK Press, 2021, embossed printed hardback, 17 x 24 cm, 128 pages

To read the book is to wander. It has no table of contents. “Vanishing,” a fourteen-page commentary by Eileen Myles that serves as an introduction, includes piercingly insightful passages about Hujar, New York, and loss, but Myles does not always name the photographs that prompt the reflections. The photographs that follow – twenty-six by Davey, twenty-seven by Hujar – are not labelled. Identifying the artist, title, or date involves flipping to two indexes at the back of the book, one for Hujar’s works and one for Davey’s; the indexes refer to page numbers, but these are printed only intermittently throughout the book and, when they do appear, are so faint as to be almost indecipherable.

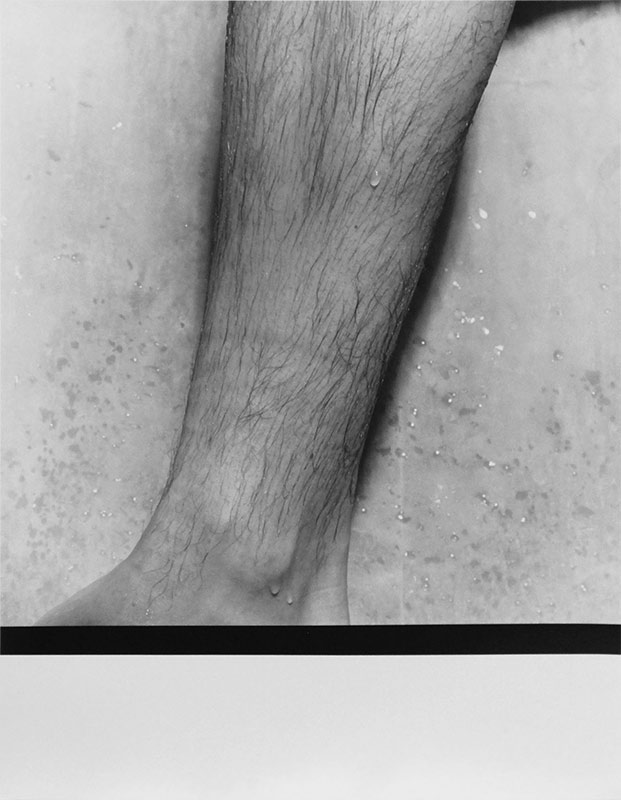

The first image is Leg (1984), an early experiment by Davey in the feminist anti-aesthetic of the 1980s. It is an uncomfortable image, clinical in its precision and aware of its own contrivance. The wet inner calf of a light-skinned person appears against an equally pale water-splattered background. Fine hair sticks to the leg, creating patterns of lines; three droplets of water refract light, like tiny lenses; faint imprints on the flesh – from recently removed socks? – striate the lower leg and ankle; the background, which seems to be white cardboard, is mottled with blotches of water that have been absorbed into it and droplets that shimmer on the surface. These details evoke drawing, photography, printmaking, and painting. Each asks us to look closely; together, they disperse our gaze. Strong shadows bulge around the leg. Perceptually, they create the illusion that the background folds forward. Semiotically, they create play between indexical and iconic signs: a triangular shadow at the top right points to part of the leg that is not visible in the image; at the same time, it continues the line of the instep in the lower left. A solid black band grounds the composition, declares the end of the photographic illusion, and forecloses on voyeuristic pleasure.

On the next page, Hujar’s Nude Torso (1979) is all suppleness and flow. A man, seen from behind, stands in contrapposto. His body, from mid-thorax to knees, is sculpted in the soft light of the studio. In Hujar’s work, the beauty of the body is one with its particularities – folds of soft flesh above the left hip, freckles, moles and birthmarks on the skin, a blanket of curly hair on the legs. Light flows into dark and back again across the image – it limns the contours of the torso and echoes its fine balance. In the background, in roughly the same place as the black band in Davey’s Leg, a hazy line defines the join of wall and floor; it continues between the model’s parted legs, creating a pyramidal patch of light at the darkest part of the image, just below his testicles. This image, created within queer rather than feminist community, is erotic and unapologetically aesthetic.

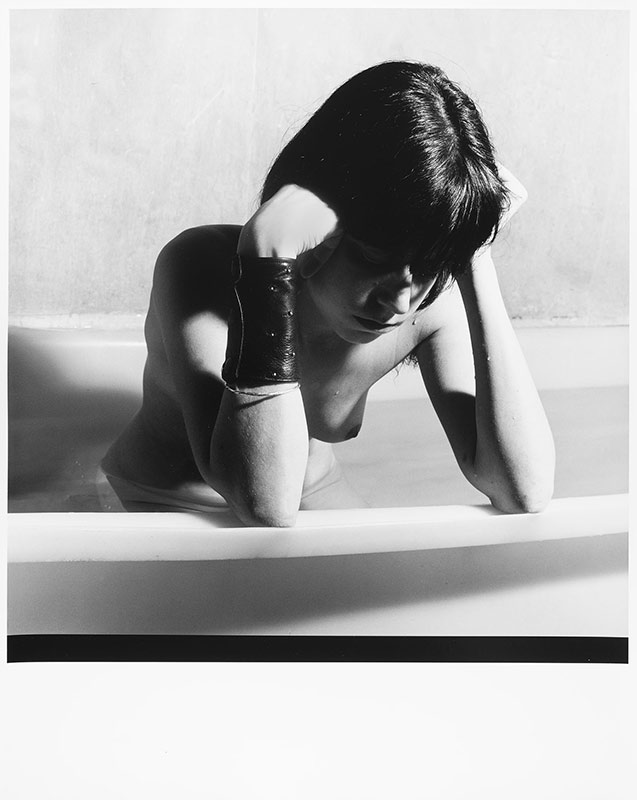

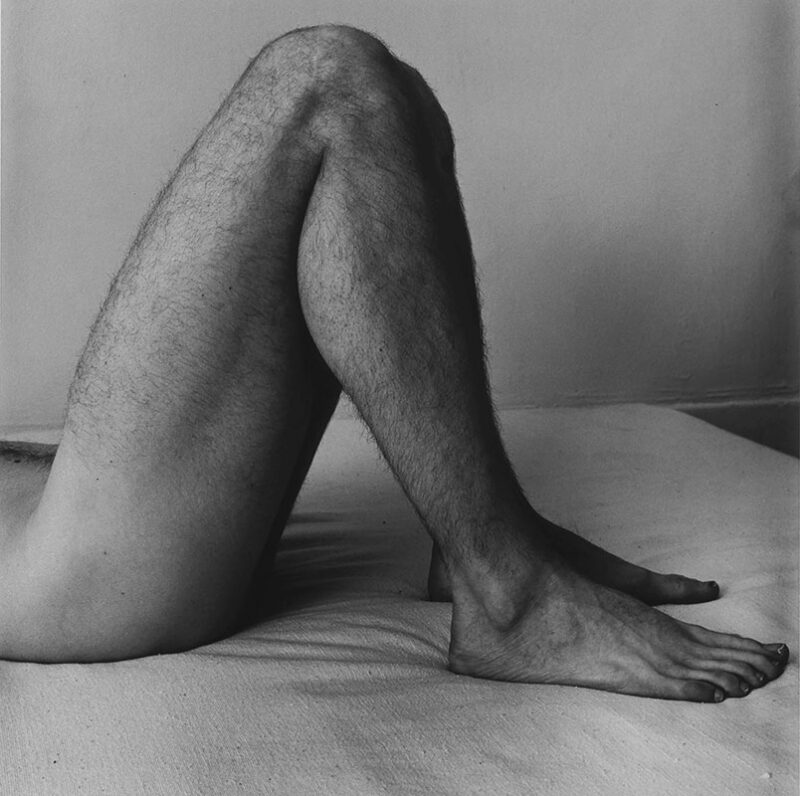

At times, there is an edgy humour to the sequence of images: a dog sitting on a bedroom floor, her arthritic hind legs splayed out under her, next to a young man, his hand holding his prodigious penis. Touch is frequently evoked: a baby suckles his mother’s breast; a young woman holds kittens against her naked pubis. Sounds erupt: a baby cries; chickens squawk. Vulnerability shades into boredom: a sister broods in a bathtub; a naked lover reclines on a bed. Throughout, the delicate mid-tones of Davey’s prints contrast with the rich blacks and wide tonal range of Hujar’s.

This contrast is especially evident in the water scenes. In Davey’s Water Print I (1991), light refracts from the gently rippling surface of a body of water. Rendered in silver tones, the image has the ethereality of a pencil drawing. Details – reflections of a shoreline just beyond view, a single pronounced wave without an apparent cause, shadows on the water in the foreground – embed narrativity in the image and draw us, tentatively, outside of the frame. In contrast, Hujar’s Hudson River (V) (1976) indicates no edge, no beyond, and no hesitation. The water is turbulent and deep, the surface is close, and the tonality – dense blacks against delicate silvers – is orgasmic in its intensity. Hujar is all in.

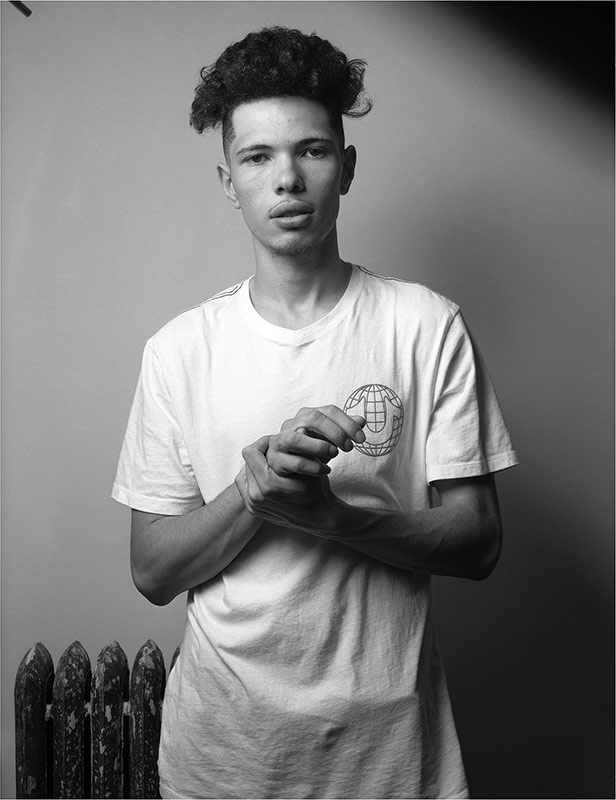

One-third of the images are newly created: they are portraits of people close to Davey – her son and his friends – and animals – chickens and horses. The young man in Eric (Fade) (2018) is the obverse of Hujar’s Nude Torso; he appears uncertain, aware of the strangeness of the moment. Light floods the scene from the left, creating shadows on his t-shirt that mimic the form of the radiator behind him and reveal the recent touch of his finger on his fly; the tip of a metal rod barely noticeable in the upper left corner reminds us of the artificiality of the situation and the precision of the composition. In Davey’s equine portraits, the animals are often off kilter, vexed by flies and on the verge of melding into the landscape. In Cisco (Landscape) (2019), the horse’s lowered neck mirrors the shape of a tree-covered hillside in the distance, the sinewy muscles in its neck extend a pattern of lines visible in the trees, and the mottled colouration of its coat echoes the slightly out-of-focus vegetation on which it walks; its head is down and its ears pulled back, signalling unease at the moment of the photographic encounter.

Notably, Davey did not choose photographs by Hujar that depict death or the “little death” of orgasm. But she did include Petite Mort (1988), a photograph of a toy shoe stuffed with a rabbit’s-foot charm that she produced the year after Hujar died of AIDS-related illness. The tiny plastic pump, with its amputated cargo peeking out from it like an engorged clitoris, combined with the photograph’s titular reference to orgasm, is the most direct reference that Davey makes to sexual pleasure and its relationship with death. In contrast, the final image in the book, Hujar’s Shoe (for Elizabeth) (1981), is pure camp. The polished leather pump is simply glamorous. It cuts a striking profile across the image; its contours are crisp, its surfaces luminous and sensual. As the finale to the sequence of photographs, Shoe (for Elizabeth) is a fitting tribute to Hujar’s exquisite sensibility and technique and a humble acknowledgment of the void that his death has left behind.

2 In an exhibition statement that is reprinted in the book, Davey writes of her post-modern generation: “We are all self-consciously trying to signal that what’s going on behind the camera – the emotional register, the labor register, the thinking register, the mechanical register, the risk factor – is to us as important as the image itself.” “Hujar,” she continues, “was the opposite. Without self-regard, he gifted it all to the subject and the image through patience, framing, razor-sharp focus and crystalline lighting.”

Laurie Milner is an art historian and art critic based in Montreal. Her research and writing focus on modern and contemporary painting and photography. She teaches in the Faculty of Fine Arts and the Liberal Arts College at Concordia University.