[March 27, 2025]

Festival Art Souterrain

Different sites, Montreal

15.03.2025 – 06.04.2025

By Jérôme Delgado

Talking about habitat during a time of housing crisis and migration issues is utterly relevant and reasonable. By making this idea the theme of its 17th edition, the Art Souterrain festival certainly manifests empathy, but above all it puts creation – and, in particular, the photographic practices of seventeen artists (out of the thirty exhibited) – in the foreground of current events. Portraying or reflecting reality remains, in this sense, photographers’ forte, even though there is no shortage of both utopias and dystopias.

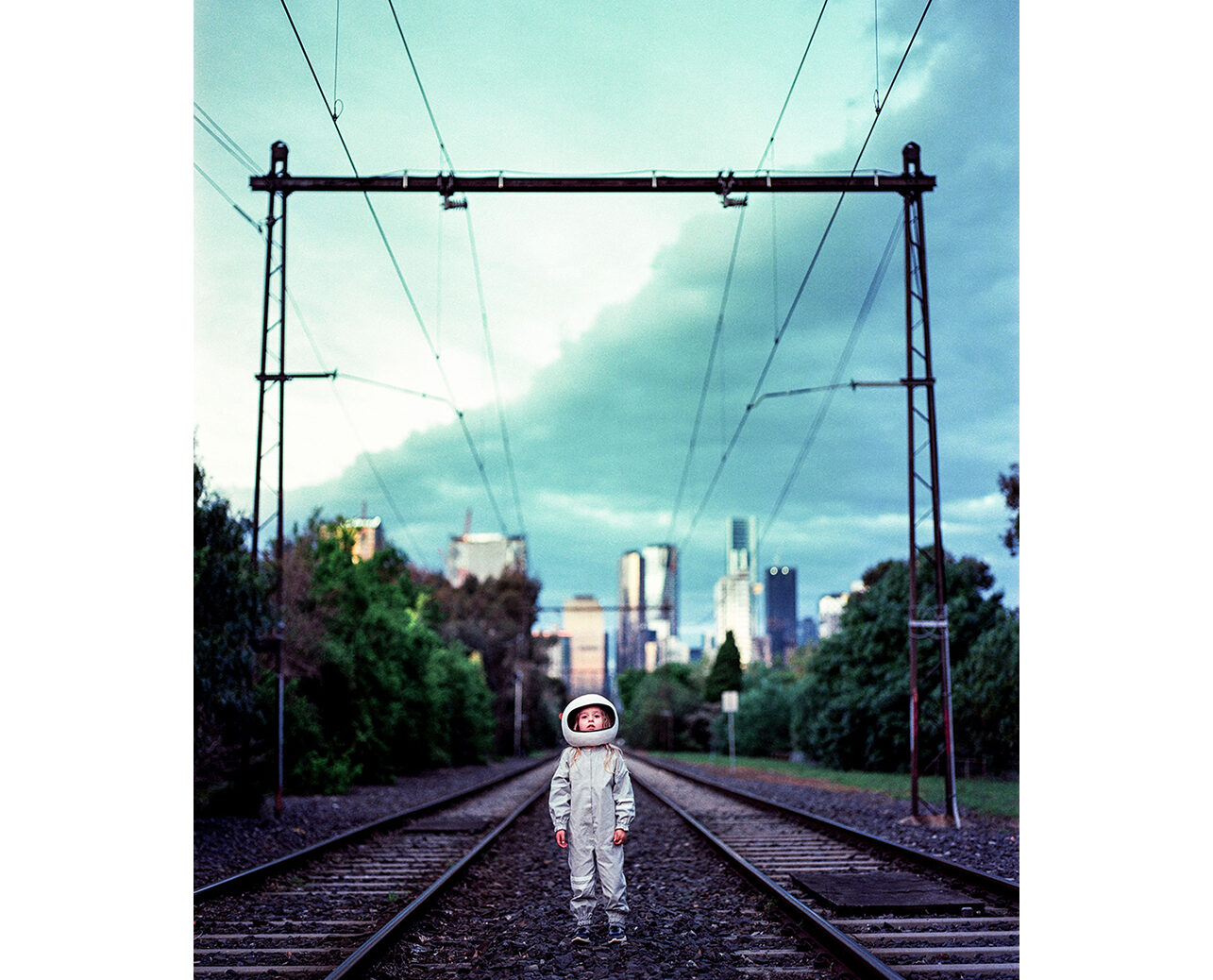

The presence of an artist such as Isabelle Hayeur and her emblematic series Maisons modèles (2006–24), enhanced with recent images, also speaks volumes: the world can’t be working very well if, for the past twenty years, finding housing or building a suitable home has entailed the same blindness, the same individualism, the same short-sighted development. In The Rocketgirl Chronicles (2021–22), Ukrainian-born Australian photographer Andrew Rovenko takes a more fanciful, lighter view. His images may depict buildings that have been neglected, abandoned, as happens in wartime, yet the presence of a little astronaut suggests that innocent play is all that’s needed to (re)take possession of the territory.

Despite the funding challenges and the possibility of attrition, Art Souterrain is staying the course with its mission of democratizing contemporary art by presenting works in public and unusual spaces in downtown Montreal – essentially, though not exclusively, underground corridors. Over the years, the event has held fewer surprises, and it has also shrunk: it covers less ground and the selection is tighter – not bad things in themselves. Overkill is not always desirable, as art projects such as Maisons modèles point out, and it has often been the weak link in the organization’s exhibitions since 2009.

The 2025 edition is heavy on photography – traceable, no doubt, to the guiding hand of one of the curators, the artist and photography professor Geneviève Thibault; the other curator, Éric Millette, with an architectural background, also chose photographers. It is surprising that, given its financial difficulties – “a complex and difficult production in the context of reduced grants,” noted the director, Frédéric Loury, in a press conference – Art Souterrain is still entrusting its program to two people. And to two visions: Thibault and Millette didn’t work in collaboration but arrived with their own lists. Given that the public space is already overwhelmed with images, it might have been wise to show more restraint.

Two types of photographic series share the walls (as well as the ceilings and floors). There are inventories – groupings such as Hayeur’s, which build a portrait of a given situation through the accumulation of similar examples. Then there are narratives, varied images that follow each other like chapters in a novel. This is the case for Rovenko’s project, in which we follow a child (Rovenko’s daughter) wearing a costume and a helmet, who spends time in places that aren’t particularly salubrious.

If census by image seems to be a highly (too?) desirable method, the initiatives that stand out are unique in their own ways. The Brussels artist Barbara Iweins’s Katalog (2016–20) takes the form of wallpaper laid out on the floor. Through a thousand photographs of her material environment, Iweins assembles a sort of self-portrait. Isolated as if taken in a photography studio, the pictures of candlesticks, electrical wires, utensils, and many other items are arranged by category, in a hierarchy based on their rarity. The appearance of a dumping ground is deceptive. She has followed a strict protocol, excluding, for example, “the immovable things in the house,” which, as a tenant, she didn’t choose.

In Édens (2022–24), Céline Lecomte, who has a degree in environmental management, makes a repertory of how we express our artificial, almost fake, love of nature. She photographed fauna and flora, made by industrial or artisanal processes, that she passed on the road in her home country, France, and in Quebec. The sheer quantity tends to be a bit repulsive, but behind the excess, she attends to meeting people where they have built their nest.

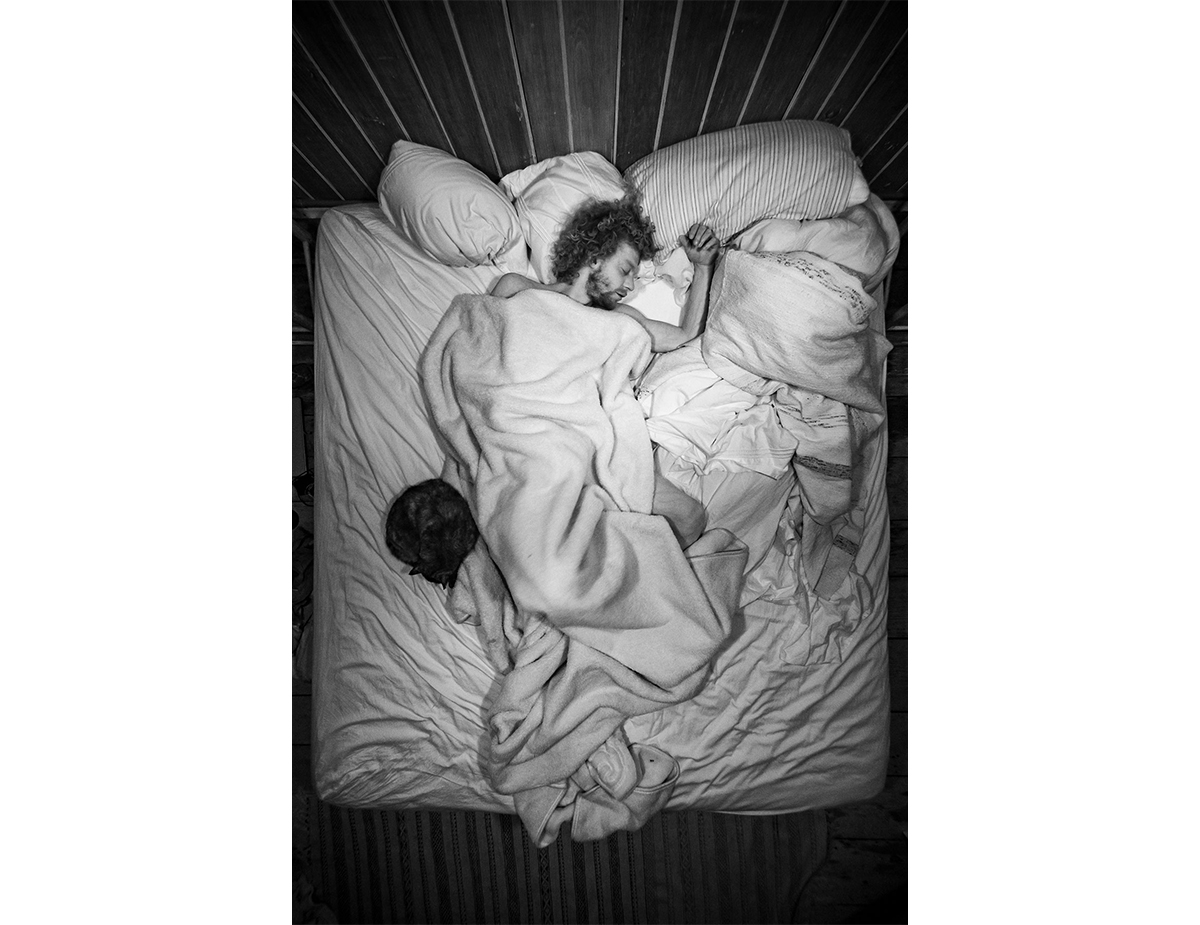

The curators mean “habitat” to be read as more than a title. It’s the place that we inhabit and that inhabits us. It’s a space of relationships and cohabitations, of intimacy and identity. Justly, many projects are imbued with affection. Éloi Perreault’s Chez nous (2020–24) documents his region of Matanie – its landscapes, its beauty, its isolation. In Maison de paille (2021–24), the most poetic narrative, Jeanne Castonguay-Carrière immerses herself in observation of the land that children – her own in particular – will inherit. Hayeur’s Radioscopie du dormeur (2020–24) elevates sleep – literally: it’s the series hung on the ceiling – to a state of unlimited gentleness, peace, and trust. Placed as it is right near Oli Sorenson’s sleeping-bag installation titled Sans-Abris (2024–25), one of the non-photographic works in the event, Radioscopie du dormeur reminds us that the sanctuary of slumber is more and more a privilege, less and less a right.

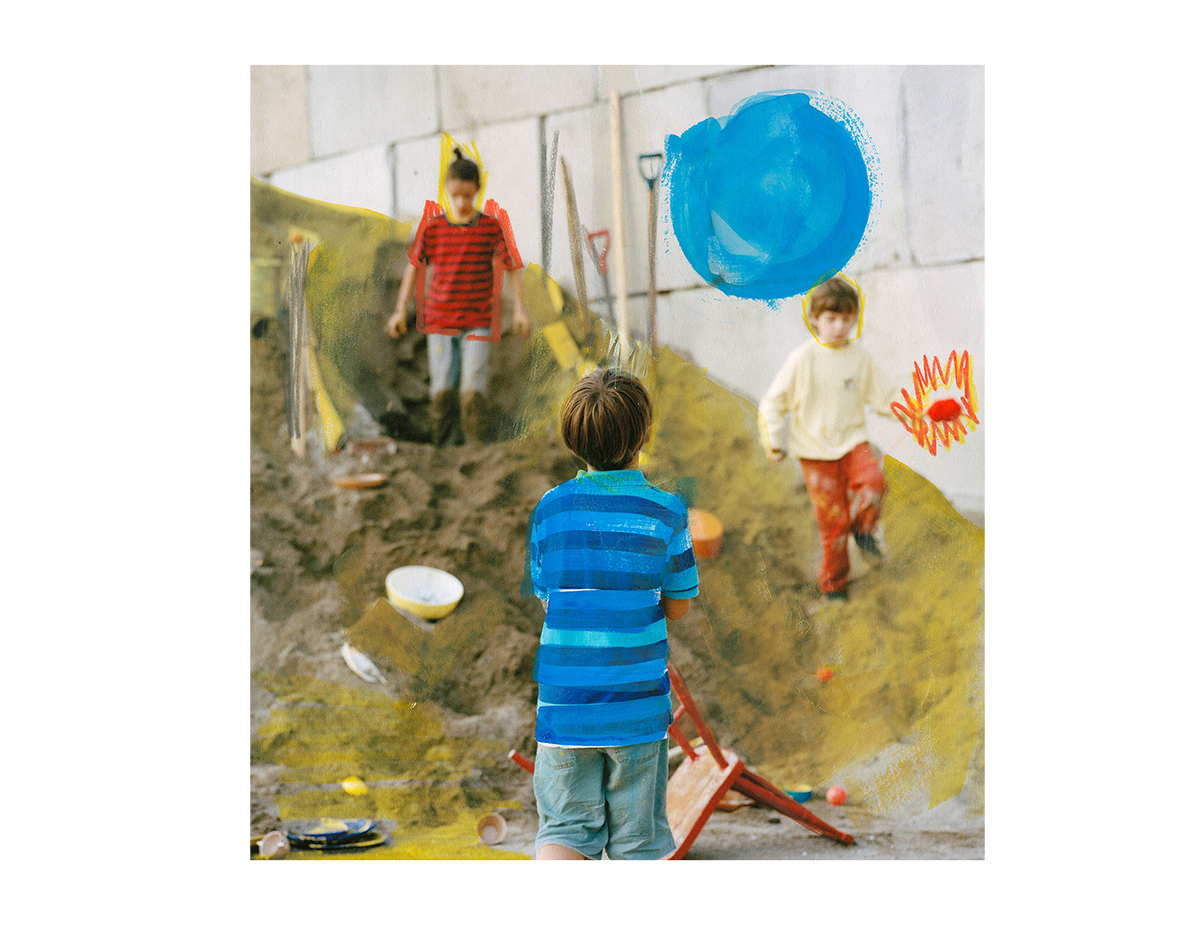

Jacynthe Carrier and Blandine Soulage stand out for adopting installation as a way to provide their image practices with volume. In Jeux et variations (2009–19), Carrier doesn’t just juxtapose photography and video but adds – or has her daughter add – paint retouches to her pictures taken from a series of visits to a concrete quarry. Soulage’s Déviation (2020–24) is displayed in a modular and fundamentally anarchic structure. For her, more than for Carrier, the presentation apparatus closely adheres to the subject of the photographs, which is the diversion of architectural spaces’ natural function – reminiscent of the exhibition Actions: What You Can Do With the City (2008) at the Canadian Centre for Architecture some years ago.

Carrier’s and Soulage’s brightly coloured photographs, like the narrative of the astronaut discussed above, direct our gaze to gestures – banal, spectacular, or anti-productive. They pose the challenge of bringing the habitat that is being reproduced on a planetary scale back to a more humane and joyous sphere. Translated by Käthe Roth

Journaliste pigiste, Jérôme Delgado occupe le poste de coordonnateur à l’édition de Ciel variable.