By Geneviève Chevalier

From the opening credits, the title of The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade as Performed by the Prague-based Experimental Theatre Company Akanda for the Patients and Staff of the Bohnice Psychiatric Hospital announces the work’s device: that of a play within a play. Here, Vancouver artist Althea Thauberger has created a re-enactment1 of the masterpiece by German playwright Peter Weiss, which was published in 1962 and performed for the first time before an audience in April 1964 at the Schiller Theatre in Berlin, directed by Konrad Swinarski.2 The production by Peter Brook, at the time the director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, onstage and then on film3 – and, especially, the translation of the text into English by Geoffrey Skelton and its adaptation into verse by Adrian Mitchell – brought the play into the public eye. This same translation inspired Thauberger to reinterpret the play in Prague, the Czech Republic, in 2012.

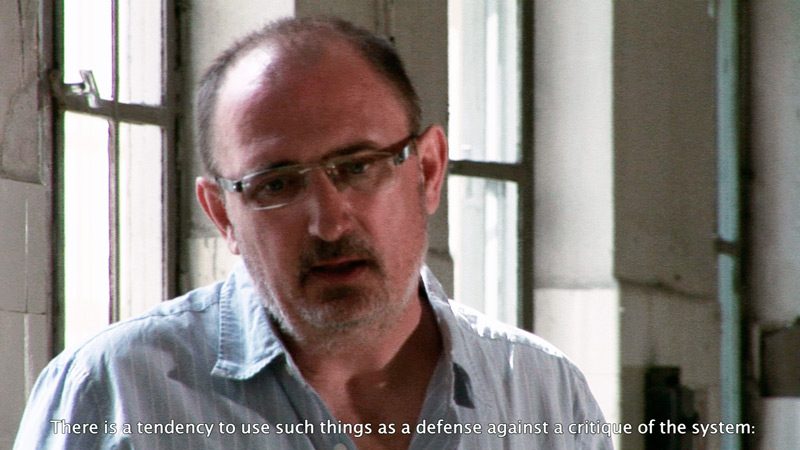

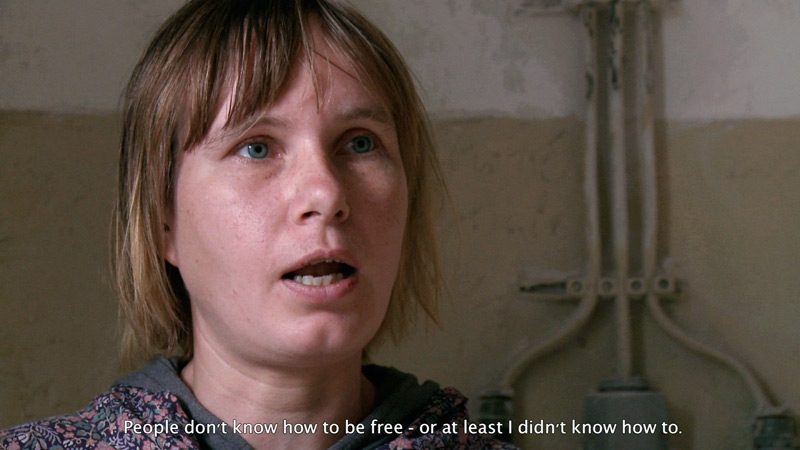

In a stunning evocation of parallels between revolutionary stories each of which engendered institutional reform, Thauberger’s reconstruction situates the action of the play in the bathroom of the Bohnice psychiatric hospital, which was built during the Soviet era and is today in the midst of reorganization. The hospital is not simply the set for the play but is also one of the objects of the play, as it refers to the space that Weiss imagined and the one where de Sade ended his days. Thauberger’s Marat Sade involves a prodigious superimposition of historical eras and events: convoked are the times of the French revolution and the Reign of Terror that followed; the assassination of one of the most fervent standard-bearers of the ideals of the insurrection of the “multitude,” the journalist, “Friend of the People,”4 physician, and physicist Jean-Paul Marat, stabbed to death on July 13, 1793; the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte; the internment, at the Charenton asylum, of the Marquis de Sade; Weiss’s play and its English-language version, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade; the Czech Republic and its Velvet Revolution of late 1989, which precipitated the end of the Czechoslovakian communist regime; the institutions dating from the Soviet era; the current patients at Bohnice; and, finally, the neo-liberal model in which we are all actors today. These space-times blend and overlap within a work whose definitive version is embodied in a video installation. In this re-enactment, numerous tableaus rush by, marked by the chants and cries of actors from the experimental theatre troupe Akanda, directed by Melanie Rada. The action is punctuated with testimonials by patients, employees, and managers of the Bohnice hospital collected by Thauberger during shooting on-site, providing the work with a new documentary character.

Re-enactments, as practised in popular culture, are related to historical reconstructions; as a recreational activity, they are performed by large crowds of enthusiasts. Since the 1990s, the form of the re-enactment has been explored by a number of artists, usually in the performance discipline, who wish to examine historical events in the light of present times or to shed light, via the past, on contemporary phenomena. A critical reinterpretation of history, the re-enactment may be situated at the crossroads of theatre, art brut, conceptual art, and video.5

Participatory from the start, Thauberger’s approach consists of “delegating”6 to certain social groups or specific communities – usually poorly represented in “official” history – the task of playing their own identity roles or calling upon professionals, in the context of works that she has conceived and structured. She has thus brought together the mentally and politically alienated7 in Marat Sade Bohnice (2012); residents from all social horizons in the Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver for the Carrall Street project (2008); wives of American soldiers living on the Murphy Canyon military base in San Diego for the Murphy Canyon Choir (2005); and Abenakis whose language is no longer spoken for Msaskok (2012), a project performed on the U.S. border, in Stanstead, Quebec. Sensitive and complex, Thauberger’s works have evolved into palimpsests over the years, as she has tackled larger-scale projects. With Marat Sade Bohnice, she has produced a work that raises, through the verbal joust between a Marat weakened by disease and a Sade at the height of cynicism, the thorny question of the relevance of becoming engaged, through the pen, in transforming the political system so that it reflects the impossible value of equality for all.

The process that led to the production of Marat Sade Bohnice consisted of a series of five performances before the public in the Prádelna, an exhibition space devoted to the visual arts and contemporary performance that now occupies the former laundry room at Bohnice. Weiss’s play, reprised by Thauberger, is articulated in two acts and thirty-three tableaus and is freely inspired by the biographies of the Marquis de Sade and Jean-Paul Marat. Sade, whose republican values had impelled him to join an early bourgeois revolutionary project, had had to fear the excesses of the Reign of Terror and of the people. Fallen into disgrace with Napoleon for writings judged immoral and subversive, he was incarcerated in 1801 in the Sainte-Pélagie prison, then transferred to Bicêtre, and finally interned in 1803, as “legally insane,” in the Charenton asylum, which he never left.8 Thanks to his rank and his friendship with the director of the institution, François Simonet de Coulmier, who firmly believed in the therapeutic virtues of theatre, he was able to mount plays with the collaboration of the asylum patients. This is where Weiss imagined Sade, in 1808, conducting an imaginary dialogue with Marat about the legitimacy of the means employed to gain liberation from oppression and injustice, and staging, with the patients at Charenton, the assassination of Marat by the young Charlotte Corday – who associated Marat with the figure of the tyrant.

Among the people performing the fictional play are the patients and staff of Charenton, director Coulmier and his family, and Sade himself. Like Weiss’s play, Thauberger’s work intertwines threads of history that belong to separate registers. However, only Thauberger challenges the contemporary spectator, through the densification of history that it creates by cutting out and linking entire layers of the story of the class struggle. In a burst of colours, textures, improbable physiognomies, and joyful cacophony, humanity’s ultimate quest for justice is embodied in the dialogue between Marat and Sade. The issues that the work raises are echoed in the here and now. And Thauberger does not commit the error of underestimating the audience: she assumes that spectators are lucid and wish to take part in an aesthetic, philosophical, and political reflection.

In this sense, Marat Sade Bohnice represents an important stage in the career of Thauberger, who is a leading artist on the contemporary art landscape. The setting of Weiss’s play in Bohnice is a true tour de force, on which a whole new level of the work is constructed. It is so effervescent and dazzlingly rich that viewing it leaves us almost breathless. But above all, the work masterfully poses the question of repetition of history, its trajectory, and the role that social classes and individuals play in it. It updates the question of the emancipatory dimension of the revolution that Marat so vehemently defended. The people of Paris, played by the mad people in Charenton, cried out about injustice in 1808, and the patients of Bohnice denounced a system that ostracized them in 2012. Marat/Sade Bohnice brings to light, through impersonation and documentary, the fragility of people who find themselves gathered outside of history.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Peter Weiss, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, trans. Geoffrey Skelton and Adrian Mitchell (Woodstock, IL: The Dramatic Publishing Company, 1964).

3 Michael Birkett (producer) and Peter Brook (director), with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Marat/Sade [film], New York, Mart Sade Productions, United Artists Corporation (distribution, 1967), c. 1966.

4 Marat founded and wrote every word of the revolutionary newspaper L’Ami du peuple, published almost every day between 1789 and 1793. See Jean Massin, Marat (Aix-en-Provence: Éditions Alinéa, 1988), 93–103.

5 Adam E. Mendelsohn, “Be Here Now: On the Ultimate High – the Retrieval of History through Re-enactment,” Art Monthly, no. 300 (October 2006): 13–16.

6 This term is employed by Claire Bishop to designate performances that are based on subcontracting – the hiring of performers, professional or not – by an artist, while also referring to the reality of globalization. See Claire Bishop, “Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity,” in Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, ed. Claire Bishop (London and New York: Verso, 2012), 219–39.

7 The feeling of alienation, which generates the feeling of being a stranger to oneself or to the society to which one belongs, is the prerogative of both the insane person and the poor person, who are brilliantly amalgamated in Weiss’s play.

8 Some of these writings were falsely attributed to him. See the case of the novel Zoloé, whose words were directed against Josephine. Maurice Lever, Donatien Alphonse François, marquis de Sade (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1991), 586–88. Sade was one of the victims of the arbitrary and the illegality that characterized Napoleon’s reign. Incarcerated for life without ever being found officially guilty, he had no right to a trial. “[The authorities] rejected all legal form: no judgment, no contradictory information, no debates, no instruction.” Sade, quoted in Lever, Donatien, 588 (our translation).

Althea Thauberger is a Vancouver- based artist who has been working in photography, film, video, performance, and public event-based works for the last twelve years. Her projects are invested in the possibilities and poetics of the social document, and of the transformative power of collective imagination vis-à-vis contemporary structures of power. Thauberger’s work has recently been in group and solo exhibitions at The Power Plant (Toronto), the Audain Gallery (Vancouver), the Institute of Contem- porary Art Overgaden (Copenhagen), and the 2012 Liverpool Biennal. She recently completed a multi- city Balkan screening tour of her film Preuzmimo Benčić.

Geneviève Chevalier is an artist, independent curator, and postdoctoral intern with the research group Collection et impératif évènementiel, directed by Johanne Lamoureux. Chevalier has completed a doctoral dissertation in art studies and practices at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) on the approach of situated curating. A lecturer at UQAM, she was previously co-conservator at the Foreman Art Gallery of Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke. Her work as an artist and curator has been presented in Quebec, Ontario, and abroad.