By Louis Cummins

By including artists such as Lawrence Weiner and Krzysztof Wodiczko, two pioneers of conceptual art who, in the late 1960s, combined art and social activism, the curators of the Biennale de Montréal 2014 clearly staked out their position:1 the art that they had decided to show was not art that takes refuge in exploration of the different formal possibilities of a medium, nor that which is presented as an ironic reflection on or critique of modernism and its institutions, nor that for which the social issues of art bear essentially on questions of identity, nor that which apologizes for or critiques consumer society, nor that which probes the meanders of the unconscious searching for a deep and tormented self. Even emerging practices such as sound art and immersive installations were put aside in favour of “narrative” video and “didactic” installations that hold an explicit discourse on the world and its potentialities. Above all, the curators sought to show works that attempt to “act on it” (as they said in the 1960s and 1970s) while posing questions about what might happen now. The idea was thus to highlight art practices that are positioned in the present and looking toward the future – a future that may take different forms, with some artists being more optimistic while others are more cynical, some more personal, others more collective, even others more transcendental; some encouraging action, others, reflection. In any case, the curators sought to show how art could transform the world and, in this regard, how practices, inevitably local and ephemeral, could have a more global impact.

With a view to eventually repositioning Montreal as an international contemporary art city, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM) and the Montreal Biennale, along with various organizations devoted to dissemination of art and culture,2 worked well together, confirming that collaboration among institutions is sometimes preferable to the potentially sterile competition that too often arises among them. The 2014 edition of the Biennale represents, in this sense, a significant success in having drawn on unified resources, at a time when the changing of the guard at the top of both institutions prefigured a desirable and welcome renewal of artistic perspectives and orientations in Montreal. However, it must be said that this merger was made to the detriment of the Triennale québécoise, which had only two editions, in 2008 and 2011, and has been relegated to oblivion; this will no doubt affect the comprehension and knowledge that we could have of Quebec art practices. Who will take over from the MACM and assume the important collective responsibility of bringing Quebec artists to the fore? We are left to wonder.

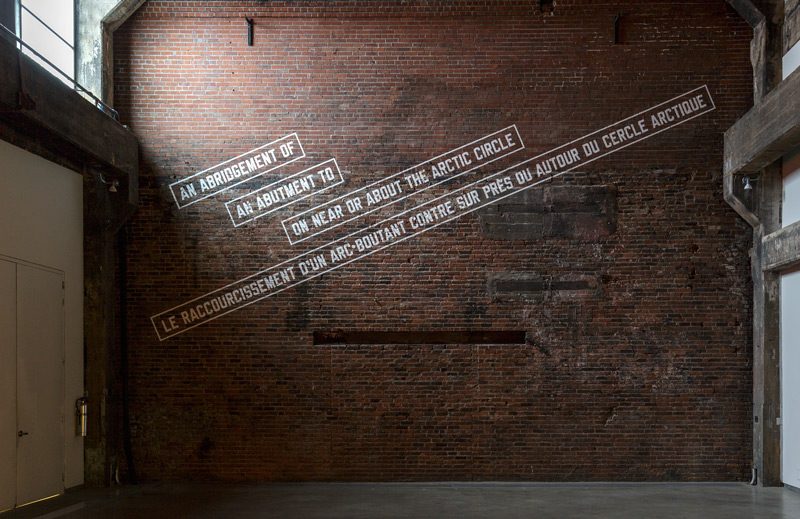

In the letter of intention signed by co-curator Gregory Burke and in the interviews that he granted to the press, he seems to consider Montreal a “locality” whose national and cultural aspirations are embodied both in Expo 67, with its techno-scientific promises, and in the actions of the Front de libération du Québec, which had the effect of sending the head offices of large corporations fleeing to Toronto and changing forever the reality of Montreal. In Burke’s view, the tensions between the modernist aspirations that belong to a bygone past are now inscribed within a much larger group of economic, geopolitical, and ecological tensions.3 To illustrate his idea, he evoked the issues involving the Arctic, the subject of artworks by a number of Montreal artists (Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens, Hajra Waheed, and Arctic Perspective Initiative) who have received recognition abroad but are not well known in Quebec. How should we understand this statement? Apparently, it seems that the Montreal Biennale has become a Canadian institution with international ambitions that is little concerned with the community that gave it birth and is still keeping it alive.

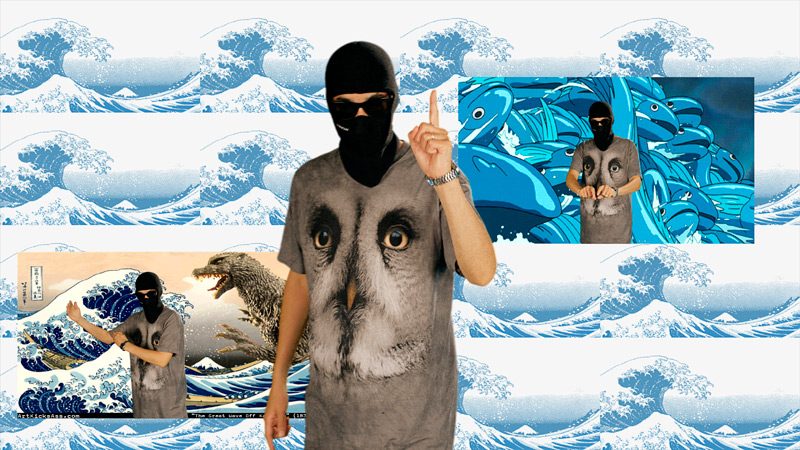

To a certain extent, this position matches the editorial orientation of the Biennale. Not so long ago, the social issues manifested in the art field were associated with identity-related questions: the presence of Aboriginal cultures, sexual belonging or orientation, cultural affiliations, and national liberation. All of these issues are now subsumed under more global questions, such as climate change and population migrations, the exponential accumulation and circulation of computer data, the considerable changes to modes of communication and culture, financial and commercial speculation, and the proliferation of surveillance devices.

In the lobby of the MACM, works by Étienne Tremblay-Tardif and Jillian Mayer suggest that the conceptual trajectory of the Biennale will involve social and cultural questions. In fact, Tremblay-Tardif’s installation, which takes us back to 1967, at the time of construction of the Turcot exchange – a Montreal expressway interchange that is now in a state of almost-apocalyptic deterioration (just as yesterday’s modernist utopias are now nothing but ruins) – and the photographic reconstruction of female nudes found on the Internet printed by Mayer on postcards that visitors can take home are both quite emblematic of our times. However, the sociological dimension is toned down in a cubicle situated nearby, where a video by Emmanuelle Léonard, Postcard from Bexhill-on-Sea, features the off-screen voices of old people in intimate conversations against a background of images of the ocean. The voices are commenting on the sense of the future when there is no longer long to live. Of course, this is indeed about the future, but in a more existential or metaphysical sense than in the more political approach of the preceding artists.

If a title wants to say something, on an institutional level, one can be both pleased and depressed about what the title of this show announces: the new synergy among Montreal institutions will no doubt be positive, but the issues raised by the grouping of markedly neo-conceptual works in this exhibition are presented against a dark cultural and social background. Furthermore, like the lifeless animals – seemingly more dead than stuffed – that Abbas Akhavan has strewn along the exhibition path, one might say that in a sort of rush to turn the page and renew our artistic world, a new guard is in the process of redefining the current era following the forms struck under the seal of austerity. What the artworks in the Biennale refer to (population migrations, obsession with speculation and so on) are facts that we cannot ignore. But we must wonder if artworks that deal with these questions in such a dry manner can contribute anything new to a collective conscience already on alert. On the other hand, a work such as Ursula Biemann’s Deep Weather has a powerful enough visual and conceptual impact to serve as an example, despite the off-screen voice that seems to whisper in our ear: the video establishes a relationship between oil-sands mine operations in Alberta and their impacts on different ecosystems, both local and global. The work’s strength has to do mainly with the images that we see in a zoom-out: a crowd of Bengalis throwing bags of sand into the sea to build dikes, in a desperate attempt to prevent flooding of their land.

The works selected by the curators of the Montreal Biennale are verbose, but their ultimate impact on viewers is debatable. Does this mean, as Mark Lanctôt suggests in the biennale catalogue when he discusses Thomas Hirschhorn’s video, that, contrary to what the preceding generation believed, images “are nothing but dregs in the rubble of the spectacular and sensational?” 4 Today, of course, we are drowning in whirlpools of images to which we have become inured. Is it possible that texts, words, speech, and sounds have suffered the same fate? We are all caught up in an extremely complex chaos of images, texts, and data that circulate in packets in incessant, turbulent flows. And in these flows, time, as we imagined it – with a present, a past, and a future – no longer exists.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 VOX, the Darling Foundry, SBC, Parisian Laundry, L’Arsenal, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Quartier des spectacles, and a few other less expected sites.

3 See Gregory Burke’s introduction in the catalogue for the 2014 Montreal Biennale: “In the end, our exhibition aims to turn to the past, from possible futures, to examine the present and address the relationships between the local and the global in this context.” BNLMTL 2014; L’avenir (Looking Forward), catalogue (Montreal: La Biennale de Montréal, 2014), 9 (our translation). Burke discusses his point of view on this subject in greater detail in Art Review, accessed December 19, 2014, artreview.com/previews/the_biennial_questionnaire_gregory_burke.

4 Mark Lanctôt, “Thomas Hirschhorn, Touching Reality,” BNLMTL 2014; L’avenir (Looking Forward), catalogue (Montreal: La Biennale de Montréal, 2014), 56 (our translation).

Louis Cummins holds a doctorate in art history from City University of New York (2003). He is an author, a multimedia artist who creates immersive installations, and an art theoretician and critic. He has published catalogue essays and articles in visual and media arts magazines. He is an exhibition curator and creates interactive and immersive videos and installations.