By Pierre Dessureault

“The nineteenth-century dispute over the relative artistic merits of painting and photography seems misguided and confused today.“1

Does Walter Benjamin’s statement, dating from the 1930s, put a final stop to the debate over whether photography naturally belongs in museums? This is the question raised by the “photo season” currently underway at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, which features three widely disparate exhibitions: a series of pictures of the province taken by American photojournalist Lida Moser in 1950, a selection of photographs of celebrities by rock star Bryan Adams, and a group of works drawn from the museum’s collection.

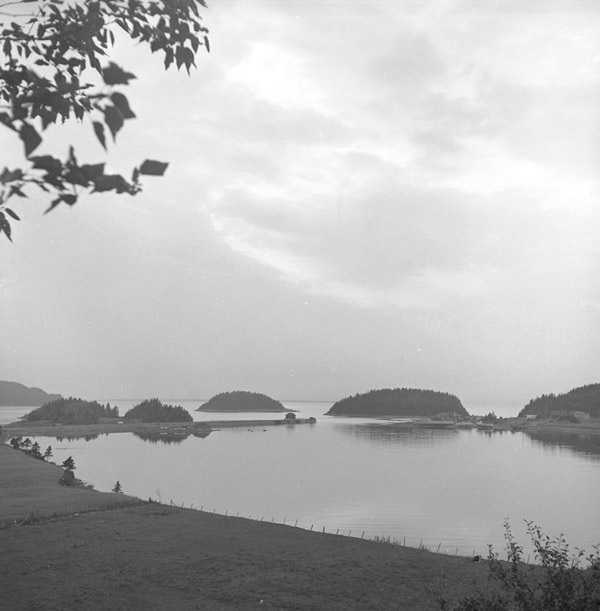

Moser. In the summer of 1950, Vogue commissioned New York photographer Lida Moser 2 to produce a report on Canada.3 When she arrived in Montreal, she met Paul Gouin, cultural advisor to Premier Duplessis, who introduced her to the city’s cultural communities and acted as her tour guide; they travelled to Quebec City and île d’Orléans, the Charlevoix region, the Gaspé, and the Lower St. Lawrence in the company of writer Félix-Antoine Savard and ethnologist Luc Lacourcière.

Moser’s photo essay was presented according to the canons of the genre: thirty photographs on six pages were accompanied by short texts that gave an impressionistic and conventional vision of Canada. Only half of the photographs chosen by the editors were taken in Quebec, and essentially the piece involved portraits of Canadian figures along with a few views of New Brunswick and Quebec, along with a few traces of urban life shot in Toronto and Hull. Produced within the rules of art, Moser’s report stood out neither for its form nor for its approach to production at the time.

A completely different approach was used in 1975, when a large number of Moser’s photographs were published in Perspectives,4 the illustrated supplement inserted in Quebec’s main dailies. This reformulation prominently featured the photographs, offering a complete range of the images made during Moser’s trip through Quebec: urban views of Quebec City and Montreal, an overview of popular culture, and portraits of celebrities that, in the view of Pierre Gascon, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, painted a complex portrait of a still-recent past. This new presentation resulted from Gascon’s multifaceted vision from within and familiarity with the subject. The few accompanying texts were limited to providing details on the images or identifying aspects of the photo essay.

In 1978, a group of Moser’s prints was displayed at the McCord Museum, and in 1982 the book Québec à l’été 1950 5 was published, combining her photographs and an essay by writer Roch Carrier. It is a strong book that, as its title indicates, documents a bygone time. Carrier’s narrative – which never alludes to the images reproduced – is permeated with his memories of the period. Although the photographs, arranged in thematic series and most reframed to create a rhythm specific to the book, were chosen as much for their documentary as their photographic quality, the visual story that they tell never wavers from a description of a time and culture weighed down by tradition.

The shift toward the museum offers a fresh reading of the photographs by creating a new space for reception that reinvents them by placing them within a context that is not a magazine story or a book but a path through an exhibition. The curator re-created Moser’s trip through Quebec. To do this, she returned to the original material behind the photo essay: the negatives and prints conserved at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. Of the some 1,700 photographs made, she chose almost two hundred, with which she associated pages from magazines, digital versions of published stories, correspondence, and contact sheets. These contextual resources returned to the images the depth that the passage of time had accumulated on their surface, with the strength of their content, the photographer’s style, and the customs of the time, as much as the cultural practices and interpretive diagrams that have succeeded them and shed a little light on their original meaning.

Most of the prints chosen were produced by Moser between 1950 and 1994, except for fifty-nine that were made for the exhibition from the original negatives. It is in keeping with this type of archival recontexualization to make prints from negatives of exceptional visual quality that have up to now been left in obscurity. On the one hand, the photograph, an infinitely reproducible object, belies the notion, dear to art history, that only the creator is able to determine the definitive rendering of the print. On the other hand, like all artefacts, photographic prints have a history, and current methodology would have been better served if the museum had indicated for each photograph whether it is a period or contemporary print rather than simply putting a general notice at the beginning of the exhibition.

The reconstruction of the photographer’s path that forms the framework for the exhibition brings out the presence and the role of her guides – who opened doors, organized encounters, and directed her toward typical sites – through portraits taken on site that allow us to glimpse their influence on Moser’s vision. This is obvious in the section devoted to storytellers, in which we see Lacourcière’s work of collecting through portraits of some of his informers accompanied by recordings made in the field. In the end, this section teaches us more about the ethnologist’s methods than about the photojournalist’s approach, as her portraits here seem incidental.

The exhibition brings together documents and paints – as do the stories and the book – a detailed portrait of the photojournalist’s trip through Quebec but buries the too-rare photographs exemplary of a strong photographic vocabulary in a social fresco with a flood of average-quality images that give the starring role to anecdotes and facile quaintness.

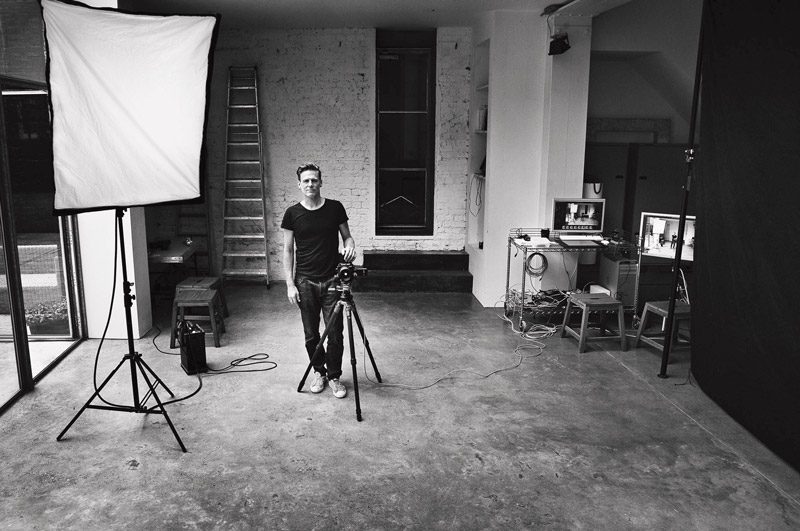

Adams. In parallel with his career as a singer, Bryan Adams 6 makes portraits of “actors, models, and celebrities”7 for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle. At the time when Moser was working, photojournalism was involved with subjects of general interest and showing current events, but today’s illustrated magazines place the priority on the rich and famous. The idea is to sell a product: fame based on the visibility for figures who vie to appear on the covers of specialized publications in images tailor-made by photographic portraits. To produce his images, Adams has every means at his disposal: an obviously well-equipped studio, assistants, stylists, and makeup artists working backstage to prepare the models. To this mobilization of resources is added the irreproachable quality of the work: careful compositions, seductive tones, harmonious colours, clinical precision, and flattering lighting to highlight the merchandise being offered for sale.

As far back as 1859, Baudelaire, in his review of that year’s Salon,8 denounced the perversion of photography as industry and the photograph as a market object ruled solely by supply and demand, whose function could be summarized as reinforcing the narcissism of the rising bourgeoisie and sanctifying its position on the social scale. Today, mass-circulation illustrated magazines have replaced the showcases of the great nineteenth-century studios in promoting the cult of visibility.

Despite the curators’ statement that Adams “captures the personality and highly charged sensibility of his subjects” in his photographs, these images are highly visible and fulfil their mission simply by being placed in full view. They are presented in the media maelstrom as pure objects of pleasure and spectacle, and the standard for evaluating them is summarized in the momentary enjoyment of consuming them.

Even in the museum, Adams’s photographs remain merchandise in the image market, as their only goal is to manufacture renown for the stars of the moment and perpetuate that renown through repetition. The celebrity of the maker of the images guarantees the models’ fame. Is it really the role of the museum to be a cog in the image-making wheel, as luxurious as those images are, and to join the cult of the catchphrase?

Another series, Wounded – The Legacy of War,9 occupies a closed space at the back of the exhibition gallery. In these images, according to the curators, “[Adams’s] images pay stunning tribute to the dignity and courage of these [British soldiers] seared in their flesh by battles [in Iraq or Afghanistan] that will forever remain graven on our memories.” In the over-sized black-and-white photographs, people mutilated by war pose under bright lights in the no-man’s land of the studio. This theatrical vocabulary, in which the contrasts in the images have been faded to a narrow range of greys that denaturalize flesh and preserve only its contours, highlight maimed limbs, disfigured faces, and bodies with stitched scars, reducing the soldiers to supporting players without any individuality but a name, an age, and the war in which he or she was wounded.

This absence of reference points reinforces the effect of artificiality for images that desperately call for a context other than that of object aestheticized by photography. This context is offered in Adams’s book of the same name, in which the soldiers’ stories add the weight of a personal reality to the pictures. It is the words of these soldiers, and not the magnified images of their injuries, that give substance to their suffering and reveal their courage.

Incarnations. The thirty photographs brought together in Incarnations 10 form a counterweight to the “cult of appearances” fed by what the curators describe as the fashion and advertising industry, which exploits society’s penchant for escape by feeding the illusion of eternal youth. Here we have the anti-Bryan Adams: is it simply coincidence or the museum’s desire to offer a different perspective on the body?

One of the exhibition’s themes is the self-portrait, which, unlike the “selfie” that is involved with the individual’s here and now, explores the presence of its creator’s world: Corine Lemieux poses in her studio, Raymonde April catches on the fly a moment of intimacy with her mother, Michel Campeau celebrates his silhouette by casting it against luxuriant vegetation, and Paul Lacroix’s shadow cast on rocks confronts minerality with evanescence. Other artists, such as Milutin Gubash and Evergon, stage themselves with their loved ones to explore the links that unite them and reveal the similarities of family.

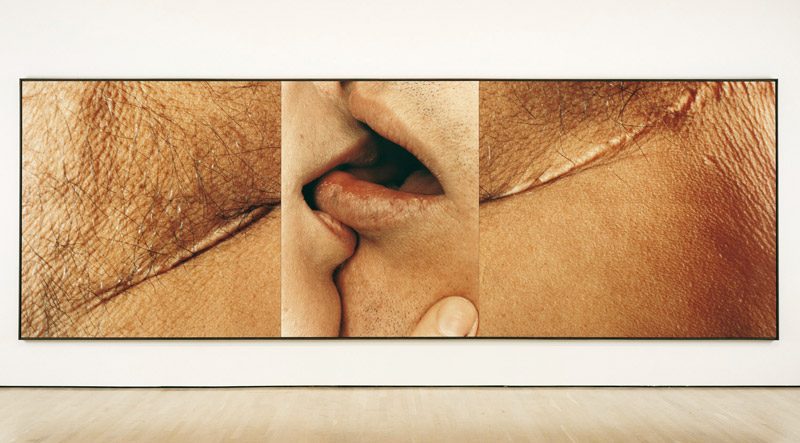

Andrea Szilasi, Éliane Excoffier, and Irene F. Whittome lend their bodies to settings in actions conceived for the camera, which gathers their traces. Szilasi’s work also explores photographic material, which she cuts out and interweaves, mingling temporalities and superimposing on her performance her intervention in the material. Such work on the image is also in evidence in Geneviève Cadieux’s La fêlure au chœur des corps, in which the caesura formed in a close-up of a scar opens to lips joined in a kiss, creating a visual metaphor. Roberto Pellegrinuzzi looks at and scrutinizes faces as a territory that he explores as a multitude of fragments, which he then recomposes as an entomologist might in monumental constructions that magnify the materiality of the face.

Although the exhibition features ordinary bodies, the images by Donigan Cumming and Chih-Chien Wang are particularly touching. The men whose unusual bodies are staged by Cumming form a chorus of mourning and end a long cycle of works in which the photographer pushed back the boundaries of good taste and upset a number of conventions. Wang’s two photographs offer fragments of everyday life produced by an outline of their creator’s unique gaze: the torso striped with red marks and the chicken drumstick, both standing out against a shiny white background, bespeak, in their minimalism, a moment in which fragility and triviality come together.

These images are grouped around a theme that casts a wide net that, although it is not striking for its originality, inscribes the works presented in a double context: that of the collection, which is in a way the heart of the museum, whose mission is to conserve, interpret, and communicate knowledge about art, and that of more general knowledge of current Quebec photographic production. In this regard, the exhibition validates and highlights a wide variety of works that reflect the diversity and richness of contemporary approaches to the medium. When will other exhibitions attest to the vitality of Quebec photography?

In conclusion, the grouping of these three exhibitions in a season with photography as a theme raises a series of questions, the main one seeming to be the museum’s desire to inscribe photography in an international prospective by giving Moser and Adams starring roles. This is a relevant idea, but the points of reference chosen raise concern, as their place in an art museum in the form in which they are presented does not seem convincing.

The question of drawing attention to photographic archives is crucial today, and the museum plays an important role in this undertaking. There are many public and private archives that are simply waiting to be discovered. In this regard, the history of photography in Quebec is a field of study that remains largely unexplored.

Although it is laudable to offer contextualizations of current practices and new readings of past cultural production within new parameters, and thus to open new spaces within which images can be received, these productions are not of equal value and do not have the same pertinence when it comes to their use of photographic vocabulary. It will always be difficult to take into consideration the interest in heritage documents, which is the bailiwick of archives and of museums devoted to history and social facts, and their influence at the level of the history of the medium and its specific qualities, which is in the realm of the art museum.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 1950: Le Québec de la photojournaliste américaine Lida Moser, exhibition produced by and presented at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, February 19 to May 10, 2015. Curator: Anne-Marie Bouchard.

3 “Canada – The Enticing Neighbor with a Faintly Foreign Air. Photographed by Lida Moser,” Vogue (U.S. edition), May 15, 1951: 70–75.

4 Bee MacGuire, “En ces temps-là… Le Québec d’il y a 25 ans vu par une photographe new-yorkaise,” Perspectives, vol. 17, no. 52 (December 27, 1975).

5 Roch Carrier and Lida Moser, Québec à l’été 1950 (Montreal: Libre Expression, 1982).

6 Bryan Adams Exposed, exhibition organized by Crossover, Hamburg, and presented at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec February 19 to June 14, 2015. Curators: Anke Degenhard and Mat Humphrey. See also Bryan Adams, Exposed (Göttingen: Steidl, 2013).

7 The quotations in this section are taken from www.mnbaq.org/en/exhibition/ bryan-adams-exposed-1224.

8 Charles Baudelaire, “Lettre à M. le Directeur de la Revue française sur le Salon de 1859,” in Michel Frizot and Françoise Ducrot (eds.), Du bon usage de la photographie (Paris: Centre national de la photographie, 1987), 27–34.

9 Bryan Adams, Wounded – The Legacy of War (Göttingen: Steidl, 2013).

10 Incarnations. Photographies de la collection du MNBAQ de 1990 à aujourd’hui, exhibition organized by and presented at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec February 19 to May 10, 2015. Curator: Maude Lévesque.

Pierre Dessureault is a historian of photography and an independent curator. He has organized numerous exhibitions and published a large number of catalogues and articles on contemporary photography. He was the editor of Nordicité (Éditions J’ai VU, 2010), featuring photographs by Quebec, Canadian, and northern European artists and essays by experts in art history and the human sciences.