By Paul Paper

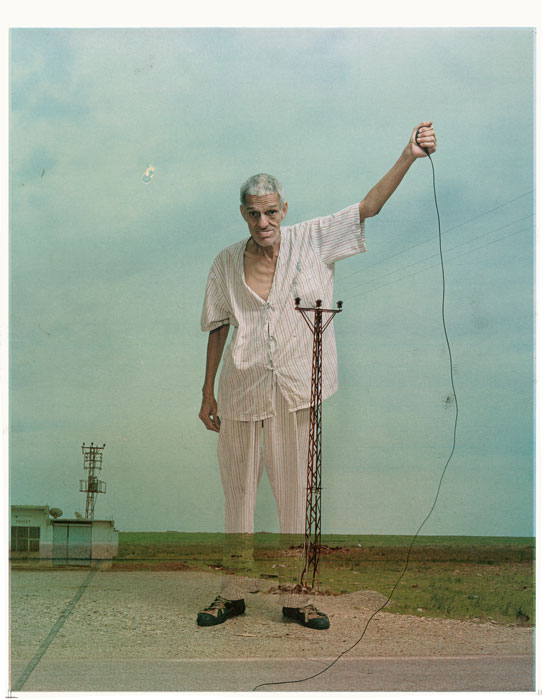

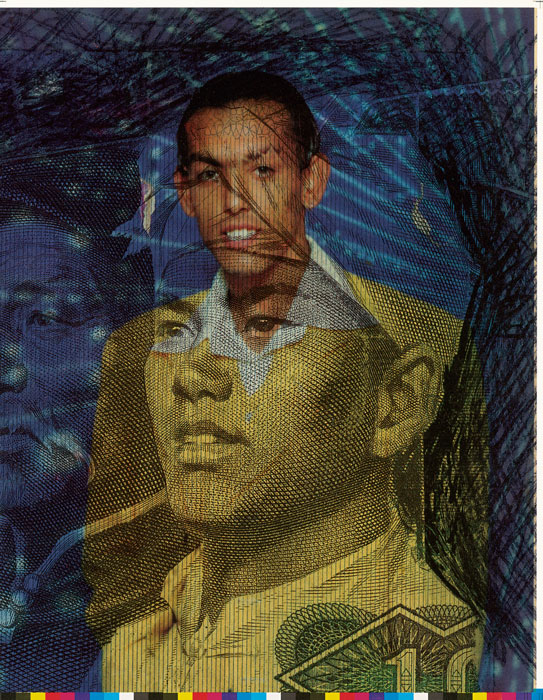

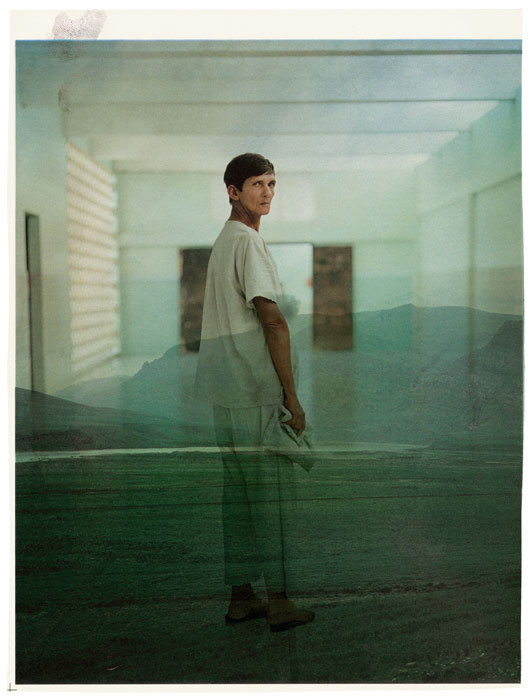

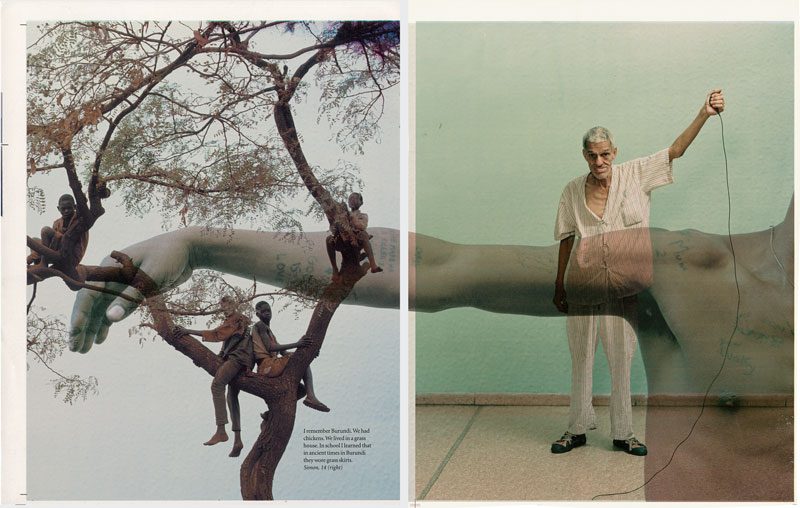

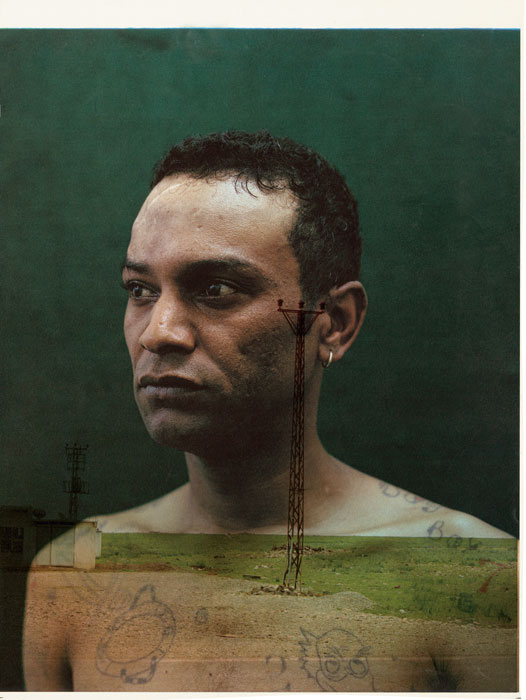

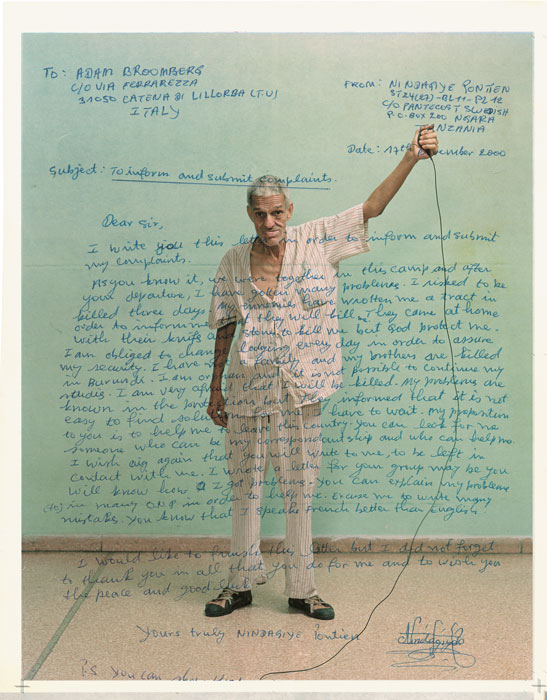

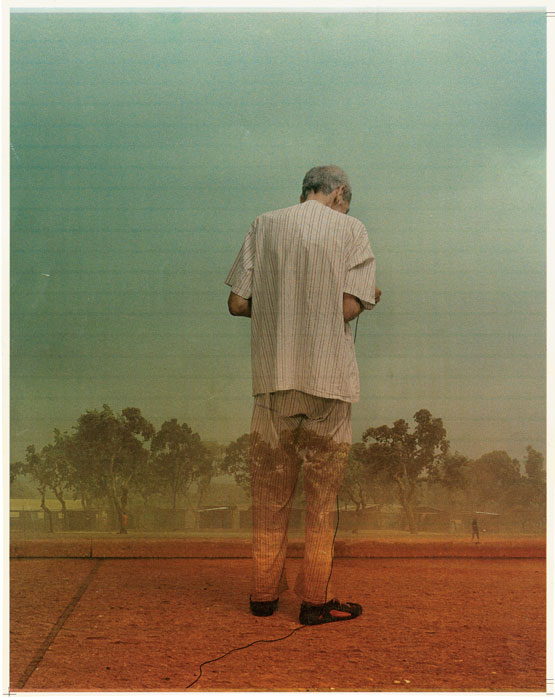

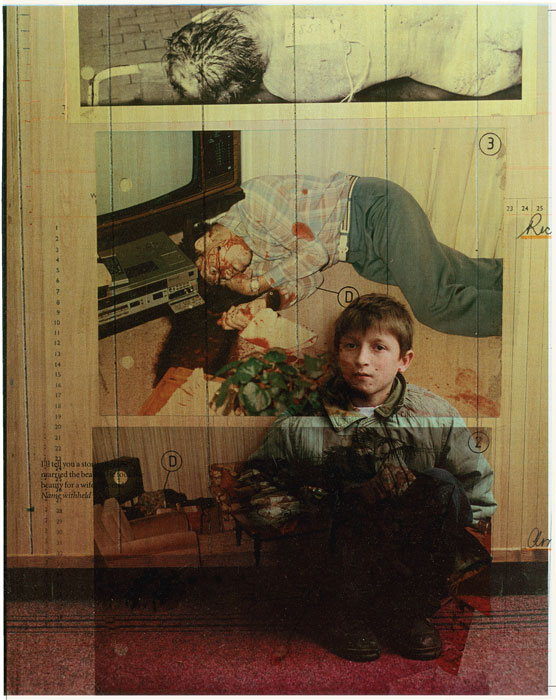

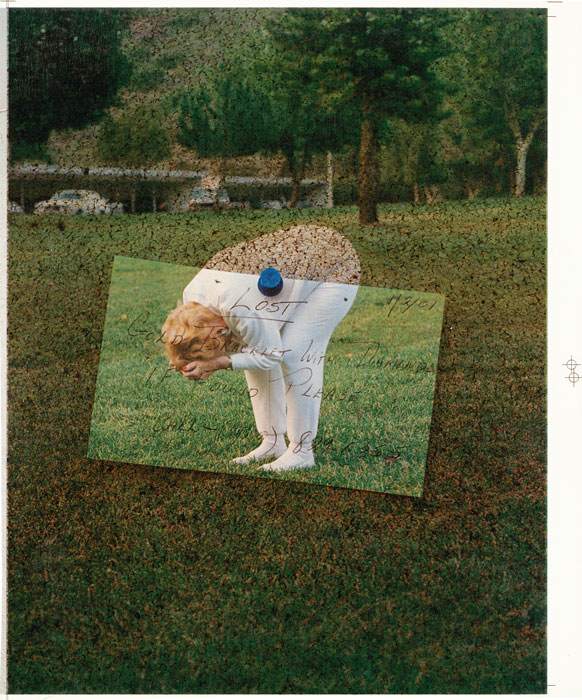

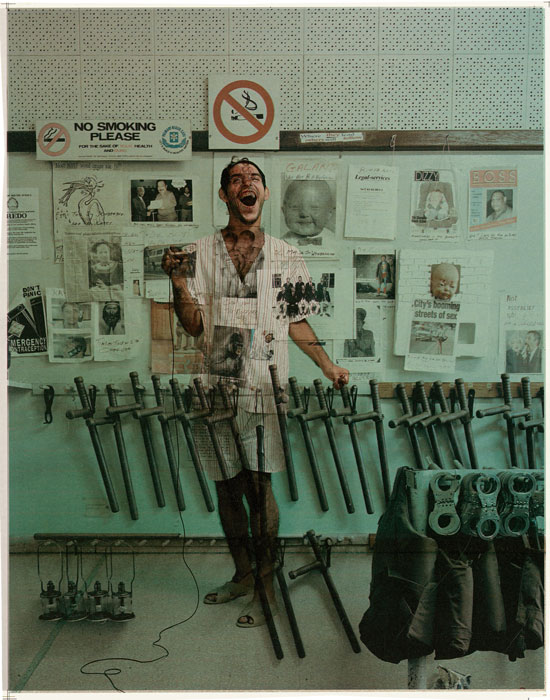

Scarti is a recent photographic series, and a book of the same title, by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. The project revives the photographers’ 2003 series Ghetto. It is, however, by no means a straight reprint. The title – Italian for “scraps” – gives away an important aspect of this reuse. Scarti di avviamento is the technical term for paper that is printed twice to clean ink drums between print runs. These doubly exposed sheets usually end up in the dustbin, but the late publisher Gigi Giannuzzi saved the Ghetto scraps for their uncanny beauty. When, a decade later, the photographers saw the preserved “collages” – in all their happenstance charm – they decided to make a book from them. What is truth in photography? It is a question with which Broomberg and Chanarin repeatedly engage, and Scarti approaches it from an unexpected angle.

The traditional view sees photography as a representational medium. Each photographic image does more than depicting the world – it represents what it depicts. Roland Barthes, in his famous book on photography, longing, and loneliness, wrote, “A specific photograph, in effect, is never distinguished from its referent.” 1 He went on: “It is as if the Photograph always carries its referent with itself . . . they are tied together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures.” 2 This evocative description illustrates the special link at the foundation of the myth of photographic objectivity.

In recent years, the notion of photography as medium of representation and documentation has been radically rethought. Not only practitioners and theorists but the general public feel a pronounced change – a change so dramatic that we are still dizzy in its wake, trying to figure out where to situate photographic images within our culture and whether they have any quality at all that would separate them from other images. Photographs now are embeddable in endless different contexts, courtesy of a network culture in which we all participate. Who creates the message is the question being asked again in the wake of countless images being “curated” not by authors or curators but by those who were habitually found on the opposite side of the authorial dichotomy – the viewers. Viewers not only construct collages that give new meanings to found photographic footage, but they also divert much of their photographic intake to these virtual visual channels, in which authorial intention is often lost or displaced. The very borders and foundations – cultural and literal – of the image and its meaning have begun to dissolve.

Photographs have become fleeting. They are no longer photographs-tied-to-referents but images-to-be-reused. The undoing of traditional photography aroused a sense of doom and nostalgia for some, while opening possibilities for others.

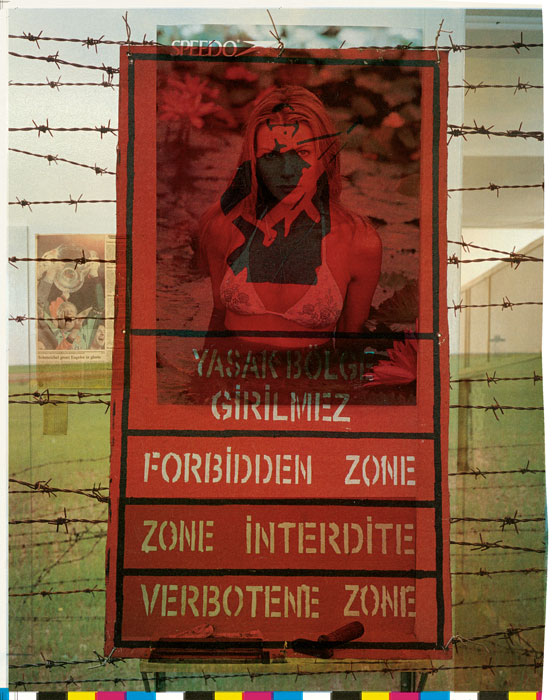

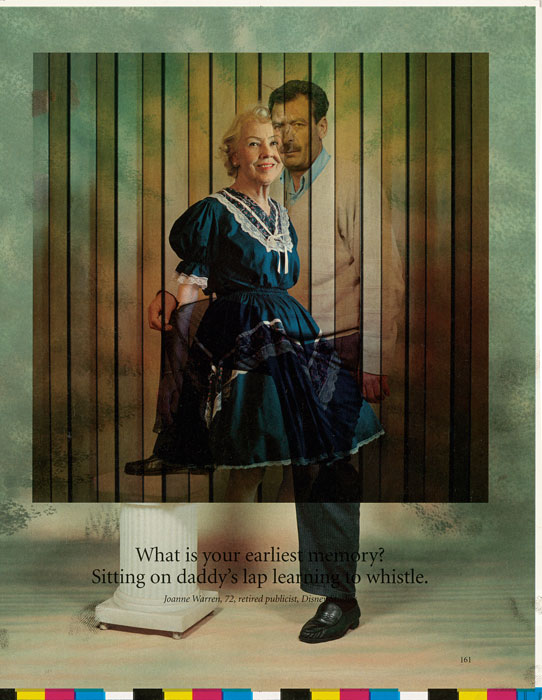

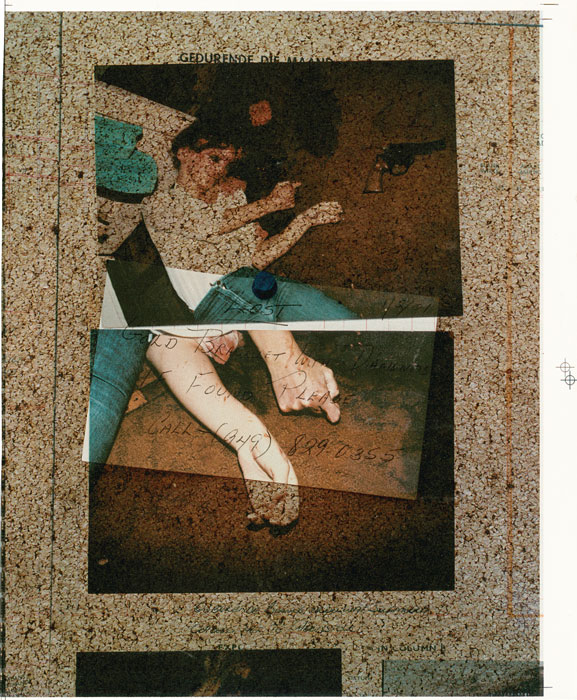

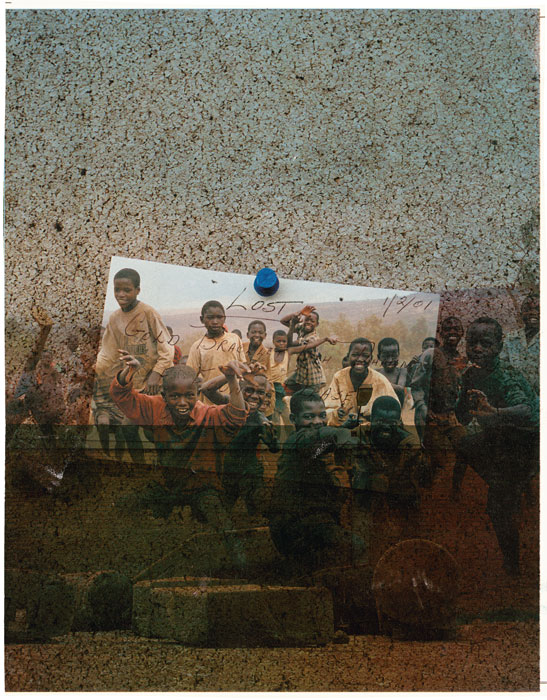

In Broomberg and Chanarin’s response to this radical reformulation, Scarti, what has been literally discarded is recovered from the dustbin and presented as artworks. The by-product becoming the original comes from its embeddedness in a new, and fitting, context. It is interesting to think about the very words “refused piece” in the setting of this project. A scrap is something unwanted, something hidden from view or thrown away in the process of reaching for something else, something that is worthy of keeping. Scarti recovers double-printed residues from Broomberg and Chanarin’s decade-old photographic work Ghetto, which documents inhabitants of twelve contemporary gated communities around the world. Most of them, too, are unwanted.

They are confined within boundaries, because for the majority, they are, like scraps, something to be hidden from view. It takes a special sensitive eye to see scraps situated on the fringes of what’s acceptable. What is difficult in Scarti is not the process of recovery itself, but the decision to recover.

It is in the networked image that the processes of deand re-contextualization become highlighted. These strategies, to a large extent, power the functioning of photographic images today. Photographs are constantly re-anchored. Blogging, social media sites, even traditional journalistic platforms constantly and repeatedly wrench photographs away from their original contexts and re-embed them to create arbitrary meanings. This arbitrariness is openly individualistic; on a more philosophical level it claims the right for people to “construct” reality as they wish.3

If photographs were once made specifically to function in series – and were quite safe within these boundaries, which tied them to a certain meaning – now images are constantly reshuffled online. It is a Wild Wild West of photography. Captions are lost and misplaced. Intentions go astray. The rules are few, and even fewer follow them. The sheriff has no gun. In this Wild West of networked photographic nomads, heroes, and renegades, the traditional values – objectivity, truthfulness, and the special photographic relationship with the “real” – are displaced by the ever-looming potential of de-contextualization of any photograph anywhere. No image is safe, once it enters the WWW.

Scarti embraces re-contextualization. It is what gives the series its meaning. Juxtaposition of seemingly random elements is another key feature of the project. We see some of the same images, in different versions, overlain with different visuals. As these manipulations have not been performed deliberately by the artists, it is randomness itself that manifests in the diversity of layering. Another important feature is the combination of images with text. French philosopher Jacques Rancière has noted that in the contemporary image economy, what is visual is no longer separable from what can only be written.4 Indeed, these two realms overlap in Scarti, in which stray combinations are created from photographs and displaced text. What these composites proclaim is not a unified message – as was common in traditional collage – but the very idea of displacement. Textual and visual elements merge into units to be used, reused, and combined. On a cultural level, the serendipitous nature of Scarti is characteristic of the recent rise of randomization in art photography, whose practitioners are exhausted with the idea of the “objective” and calculated gaze.

Scarti interestingly mirrors Broomberg and Chanarin’s own transition from documentary projects (embedded in a belief of photographic veracity) to more constructed works. Although the raw material in Scarti is images from the Ghetto series – which was still very much influenced by the traditional understanding of photography – the result is a complication of this understanding and a questioning of the value that we implicitly give to photography. Instead of reinforcing the ideal of truthful medium, the newly constructed images highlight that photography is, and always was, a mediated gaze. This reflects a wider cultural shift in the perception of photography and its place within visual arts and culture. Photographs are no longer truthful and objective documents of the real, but merely images to be used by embedding them into different contexts.

Scarti is symptomatic of how photographs and images are used and reused in our culture, giving meaning through context. It is, thus, a contemporary photographic work per se. The potentiality of re-contextualization is a key component of today’s photographic image. It is these not-realized-yet opportunities that define each and every photograph. There is a sense of levelling in this – a sense that all things are levelled by the gaze of photography, because it matters less what was in front when the image was taken than the potential use that this image might have in one of a myriad of potential contexts. Therefore, the link from a photograph to its referent – glued together “limb by limb” – is blurred and weakened.

What is reformulated in Scarti is the relationship with an older kind of photography, one imbued with unshakeable trust in photographic veracity, in a way that fits with the contemporary culture of networked images.

Paul Paper was born in 1985 in Vilnius, Lithuania, and lives and works in Vilnius and London. He is a photographer, writer, and curator. His recent project Blog Reblog features two hundred images by two hundred photographers. It reflects the challenges of curating photography in a network-empowered culture and was presented at the Austin Center for Photography.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin are artists living and working in London. They have had numerous international exhibitions, including at the Museum of Modern Art, Tate Galleries, the International Center of Photography, the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, The Photographers’ Gallery, the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art, Museo Jumex, and Lisson Gallery, London. Their work is represented in major public and private collections, including the Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Musée de l’Élysée. They received the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2013 for War Primer 2 and the ICP Infinity Award 2014 for Holy Bible. Recent and upcoming exhibitions include Conflict, Time, Photography at the Tate Modern, the Shanghai Biennale 2014, and the British Art Show 8.

www.choppedliver.info

2 Ibid. (emphasis added).

3 This contemporary functioning of images is emblematic of wider cultural changes: the abstraction of capital and social relations, the gradual disappearance of the visible physicality that grounded the causal relations of the Newtonian world.

4 Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image, trans. Gregory Elliot (London and New York Verso, 2007).