Douala.1 Late January 2015. I take my first steps on the streets of this port city, the economic capital of Cameroon. Douala is a vibrant city that constantly eludes your grasp. First steps and already some reference points. We cannot speak of the contemporary scene in Douala without speaking of the art centres that form its identity. For in Douala, a city with a troubled past and an uncertain present, art is in the street, where artists intervene in a concrete way. A perfect example is the monumental statue in the Deido traffic circle, La nouvelle liberté by Joseph-Francis Sumégné – commissioned in 1996 by Doual’art – which has become the symbol of the city.2

To talk about photography in Douala and, more generally, in Cameroon, is to evoke its rich history, open to all influences. A few major names have emerged, such as George Goethe (1897–1977), born in Sierra Leone, who opened the first studio in the city, Photo George, in 1931. In 2015, another name is on everyone’s lips when I ask to meet a photographer: Nicolas Eyidi, who is a bit like the “father” of the Doualan scene along with Photo George, with which he collaborated when he was starting out. A documentary photographer, Eyidi has been a freelancer since 2000; he forms a power couple with his wife, Rose, who manages a bank of exceptional images on Cameroon.

What photography exhibitions are happening in Douala right now, in early 2015? Galerie MAM, a beautiful light-filled space, offers African Spirits, the most recent successful series of self-portraits by Samuel Fosso, an internationally known Cameroonian artist. In an annex of the Institut français, an exhibition of a different type introduces viewers to historical photographs of the chiefdom of Bandjoun, in western Cameroon. But the site that has launched Doualan art photographers is incontestably Doual’art, an influential contemporary-art centre since the early 1990s. The artists that I mention here have all had shows there.

It has taken time for photography to emerge as a form of expression on its own in this city of visual artists that favour painting and sculpture. Certain established artists, such as Hervé Yamguen, Hervé Youmbi, and Goddy Leye, have adopted the medium, and it is important to a new creative generation exemplified by Patrick Wokmeni and Em’kal Eyongakpa. Each of these artists continues, however, to move from one medium to another, experimenting freely in this city, where art is exhibited under an open sky.

From Cultural Desert to Visual Arts Capital.3 In the shade of mango trees, the Doual’art centre, where the art movement that today enlivens the city was born, is above all a place that gives artists a voice. One of its founding pillars, Didier Schaub, bowed out in November 2014. But this didn’t stop the flow of voices, as evidenced by the tribute paid to him in an exhibition bringing together several members of the artistic family that perpetuates the spirit of this contemporary art centre turned toward the street, toward people, and toward Douala.

Today’s Doualan scene emerged in the 1990s, through democratic transitions. It was a chaotic period for Cameroon, but under the pressure of popular and international pressure a certain opening was created. Doual’art was founded in 1991 in this propitious context. Its founders, Marilyn Douala Bell and Didier Schaub, worked tirelessly to transform the city – to imbue it with an identity, a soul – by making Doual’art a space for creation, dissemination, and reflection for all.

“We kept the fire burning until 2005,” summarized Bell; that was the turning-point year, when the first Ars & Urbis symposium, a sort of think tank in partnership with the university and the Douala urban community, was held. This led to SUD – Salon urbain de Douala – a triennale organized by Doual’art starting in 2007. SUD is a “festival of visual arts that takes the city of Douala as both object of study and site of production.”4 The artists invited to SUD work in situ and produce, after three years of close exchanges with the city and its art community, works inaugurated during the week of the festival. Doual’art is, in the end, a bit like a family having a conversation in a spirit of healthy competition, sharing its knowledge, and playing a role in the fate of the city and its inhabitants.

Douala “Took Body Blows.” In Douala, very few visual artists identify themselves as photographers in the strict sense of the term, even though they have all been involved in the medium in different ways. It was no doubt through the issue of the body, this colonized body,5 receptacle for alienating emotions, that the first strong works emerged. Douala “took body blows,” 6 and if it was still breathing, it was in part thanks to its artists. Hervé Yamguen, a painter and poet, was the first to open the door by producing a number of series of self-portraits, starting in 2001. Two years later, he photographed other imperfect, sensual nude bodies in motion, which he presented at Doual’art in an exhibition-performance, Le corps certain (The certain body), “a body simply posed in a strange or moving setting, trying to find its place,” wrote Didier Schaub.7 The body became the support chosen by many to challenge the quirks of the city, and of society, referring to Frantz Fanon’s “ultimate prayer” in Peau noire, masques blancs (Black Skin, White Masks): “O my body, make of me always a man who questions!” 8

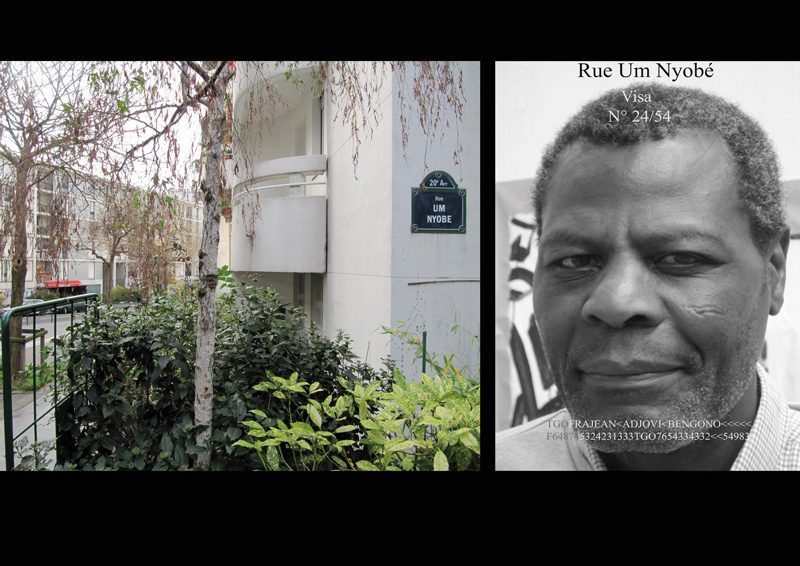

Cameroon, a “deep well filled with silences,”9 had a violent colonial history and is still struggling with the ghosts of its past. Hervé Youmbi’s mural installation Cameroonian Heroes, created in the courtyard of the Doual’art space for SUD 2013, recalls this fact: “A series of five portraits of strong personalities of the Cameroonian nationalist battles. Because they died in combat, these figures of Cameroon’s contemporary history are recognized by the people as heroes – contrary to the political power in place, which, to date, has refused to honour them.”10 In the last few years, this multimedia portraitist, whose main concern is the notion of identity, has taken a resolutely political turn in his work, as demonstrated by Rue Um Nyobé (Um Nyobé Street, named after the Cameroonian resistance fighter killed in 1958 by French colonial authorities), an installation produced and presented in Paris in 2009, composed of photographic portraits of residents of Belleville who, through the magic of Photoshop and photomontage, become witnesses to history.11

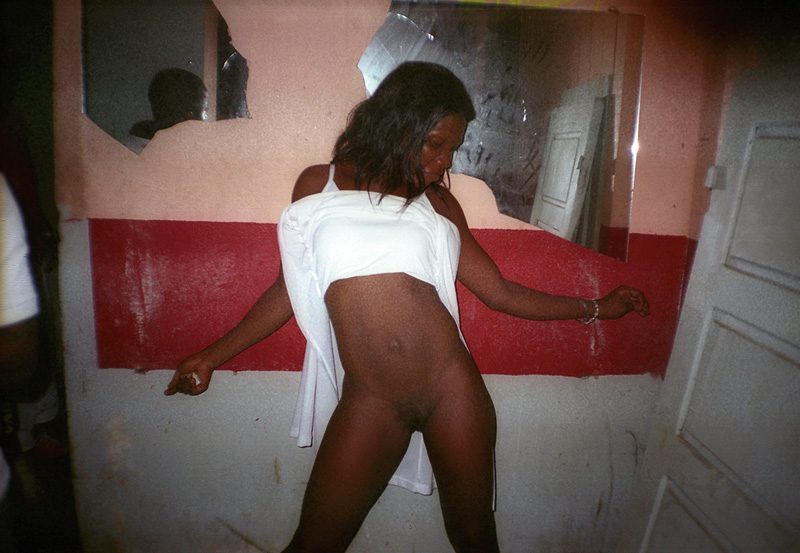

It takes courage to “bluntly smash the silence.” In 2006, Patrick Wokmeni went to his childhood neighbourhood to take flash photographs of the prostitutes there, not wearing their make-up, caught between excess and despair. “His images are marked by the intimacy that he establishes with his subjects; photographed in scenes of daily life, they show no modesty or shyness in front of the lens.”12 Following the interception of an exhibition catalogue that included this series, Les belles de New Bell, on the way to Berlin, Wokmeni, who had also produced a series on the 2008 riots, decided to leave his homeland to continue his photographic work in Belgium.

Douala is where the protest movement of February 2008 began, in a country with an “extremely young people led by extremely old men.” 13 The 2008 riots, the largest since the “dead cities” operation of 1991, began in Douala and spread like wildfire to other cities, including Yaoundé, and to the western part of the country. Douala is at the leading edge of both political protest and artistic protest with Doual’art and ArtBakery (an art centre opened in 2003 by the artist Goddy Leye in Bonendalé, a Doualan suburb), which enable artists to find their bearings by positioning themselves within a conscious process.

“Art Is Not Dying This Evening.” With the cooperation of artist and researcher friends, Hervé Yamguen and Hervé Youmbi, “pathfinders” and members of the Cercle Kapsiki visual artists’ collective formed in 1997, created a performance called RING for SUD 2007. It was a milestone in the history of contemporary Cameroonian art. In 2002, Cercle Kapsiki had given more than fifty paintings to the Musée National du Cameroun in Yaoundé in the hope that the museum would display and purchase them. But the museum kept none of its promises; the artworks gathered dust for five years in its storage areas, suffering irreparable damage, and were never returned. In an ultimate act of resistance, the collective decided to take back these artworks, at least five of them, to burn them in public at ArtBakery. And on this December evening in 2007, Goddy Leye declared to the gathered crowd that was watching, emotional and powerless, as the works were destroyed, “Art is not dying this evening. Art is more alive than ever. And this art that you have watched burn here will be reborn, will be reborn more than other. It is a cry of anger, but also a cry of hope, because if we cannot revolt, we can do nothing.”14

Fireflies in the Night. Before he died suddenly in 2011, taken prematurely by illness, the “smuggler” Goddy Leye had the time to lay solid groundwork with his ArtBakery project. This genius of a multimedia artist played an essential role in the opening of the visual-arts scene to women, such as Justine Gaga (painter and sculptor who took the torch for ArtBakery), Ruth Belinga (painter, video artist, performance artist, and professor at the Institut des beaux-arts in Foumban), and Ginette Daleu (painter and photographer), whose career was described in the first issue of Intense Art Magazine, published in October 2014.15 For SUD 2013, Daleu photographed the crumbling walls of Bessengue, a poor neighbourhood of Douala, as if to exorcise her own anguish. This series, Les introuvables, magnifies the details of temporary shelters made with various materials in various colours. Another promising artist, Boris Nzebo, also attentive to the pains of Douala in his series Ville surprise (2012), launched “an appeal to all those who have lost their head, lost their reality, and become detached from their context.”

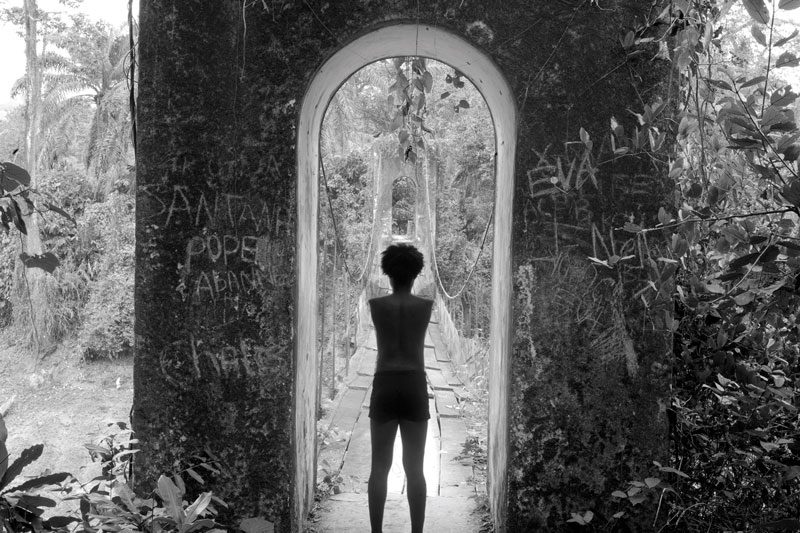

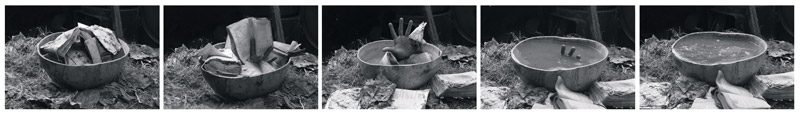

In another grand gesture, in 2011, Doual’art brought together for the first time in an exhibition two rising talents in Cameroonian photography: Patrick Wokmeni (mentioned above) and Em’kal Eyongakpa, who produces installations and performances to create interactions among his favourite media (photography, video, and audio). Nominated for the Prix de photographie Aimia – AGO in 2013, Eyongakpa has since been constantly involved in exhibition projects and residencies. In his images, which come straight from the world of dreams, he compares human beings seeking spiritual and physical freedom to “thirsty fish in water” (Bleed for the Read Pentaptych, 2009). In Naked Routes (2011), he embedded his own nude body in historic Cameroonian landscapes. These young rising artists are like “fireflies obstinately blinking in the anthracite night,” in the words of Lional Manga – fireflies that gives us the hope for glorious tomorrows for contemporary Cameroonian photography.16

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 See, on this subject, Dominique Malaquais, “Une nouvelle liberté ? Art et politique urbaine à Douala (Cameroun),” Afrique & histoire 5 (2006): 111–34.

3 “Our objective is to make Douala the regional capital of visual arts,” stated the founders of Doual’art, Marilyn Douala Bell and Didier Schaub, in an interview with Robert Essombe Mouangue, “Nous voulons faire de Douala la capitale des arts plastiques,” Africultures, no. 60 (September 2004).

4 Maud de la Chapelle, “SUD 2013, quand l’art métamorphose la ville . . .” C&, n.d., www.contemporaryand.com/fr/magazines/sud2013-when-art-meta morphizes-the-city/ (our translation).

5 An example often cited was that of the kaba (a word that comes from the English “cover”), a very enveloping dress worn by women on the coast since the 1840s and 1850s. This garment was imposed by the wives of European missionaries, who tolerated no nudity.

6 Lionel Manga, L’ivresse du papillon. Le Cameroun aujourd’hui: ombres et lucioles dans le sillage des artistes (Artistafrica and Edimontagne, 2008), 200.

7 Didier Schaub, “‘Le corps certain’ Hervé Yamguen,” December 2003, came roon_pics.voila.net/decouvrir/yamguen_expo_doualart.html (our translation).

8 Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952, quoted in Dominique Malaquais, “The Dripping Man: Art, the Ephemeral, and the Urban Soul,” African Arts 42, no. 3 (2009): 28.

9 Manga, L’ivresse du papillon, cover copy (our translation).

10 Didier Schaub writing about Cameroonian Heroes, SUD 2013, www.doualart.org/spip.php?article630 (our translation).

11 Dominique Malaquais, “Hervé Yamguen, Hervé Youmbi, ou les masques rebelles,” in Arts et cultures d’Afrique en recherche. Vers une anthropologie solidaire, ed. Myriam Odile Blin (Mont-Saint-Aignan: Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2014): 153-172.

12 Didier Schaub, “Objectifs, Em’kal et Patrick Wokmeni, du 15/01 au 10/02/2011,” www.doualart.org/spip.php?article285 (our translation).

13 See Rémi Carayol, “Cameroun: le péril jeune,” Jeune Afrique, December 26, 2014, www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/JA2 814p043.xml0/ (our translation). According to Carayol, the “average age of Cameroonians is nineteen years, more than 60 percent of them are under twenty-five, but their president is eighty-one years old, and has spent thirty-three years at the head of the country” (our translation).

14 Goddy Leye, in No Art on Two Dollars a Day, documentary by Laurent Malaquais, Cameroon, 2008, 7 min, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gb18FWbL0mw#t=368 (our translation).

15 IAM, the first artistic platform that celebrates female creativity in the visual arts, fashion, design, and architecture in Africa, was launched in late 2014 by Céline Seror and the photographer Angèle Etoundi, who became the magazine’s art director. Notable in the first portfolio of IAM, devoted to the female contemporary scene in Cameroon, was the work of photographer Sarah Dauphiné Tchouatcha, based in Yaoundé, with her latest series called Les Camerouns. Tchouatcha is also making a documentary film on the history of studio photography in Cameroon, in collaboration with the director Régis Talla.

16 As signalled by the new Collectif Kamera, which, according to the latest news, is preparing its return: collectifkamera.over-blog.com/.

Érika Nimis is a photographer (former student at the photography school in Arles, France), Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.