By Érika Nimis

Bamako Encounters 2015

The biennale in Bamako, Mali, came to an end on December 31, 2015. This anniversary edition – the tenth1 – had been delayed by two years due to a major crisis that occurred in 2012.2 Even a few weeks before the opening, there was still a climate of uncertainty,3 though it was quickly swept away by the invigorating enthusiasm of the organizing committee. Getting the biennale back on the rails was an even greater challenge because the Malian government had emerged terribly weakened by a conflict that had cleaved the country in two for an entire year. But culture had to regain its place of honour and it did so, with the logistical support of the Institut français, which took charge of the production aspect (the exhibition prints for In – the official part of the festival – and the catalogue,4 a true masterpiece of publishing designed for posterity).

Although the strengthened security measures were a source of concern, the organizers of the biennale were resolved to revive the event; they deployed their wealth of expertise, and the magic of the Bamako Encounters did the rest. The success of the tenth edition – beyond the few inevitable false notes related, in part, to the ambitions declared for this anniversary edition – was due both to the high quality of the works presented and to the strength of a team that worked relentlessly to make sure that the biennale took place under the most normal conditions possible. It was due also to the unifying determination of one woman, general artistic director Bisi Silva (whose career I wrote about in my article on Lagos, CV 1025), who was flanked by two young associate curators, Antawan I. Byrd and Yves Chatap. Here’s a look back at the programming for this anniversary edition.

Challenging Time: A Pan-African Exhibition. The call for works for this edition, the theme of which was “Telling Time,” drew more than eight hundred proposals (as opposed to 250 for the 2011 edition). Needless to say, the return of the biennale had been highly anticipated. A total of thirty-nine artists (or groups of artists) “told time” in images in the pan-African exhibition at the Musée national; the uncluttered scenography was intended, above all, to give each work enough space to breathe. The challenge was to express, through fixed and moving images, multiple temporal realities: the past, the time of history, its icons, and its ghosts; the present, perception of which is still chaotic, submerged in the tides of revolutions and migrations; and the future, time of fiction, bearer of possibilities.

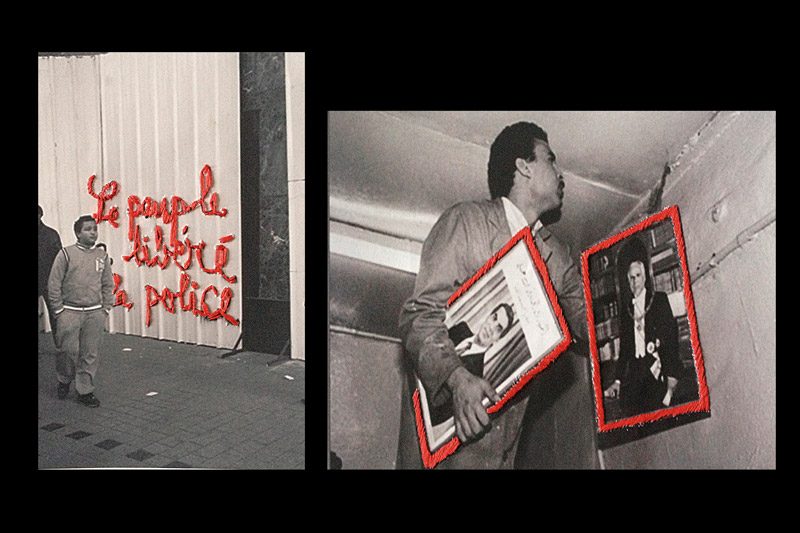

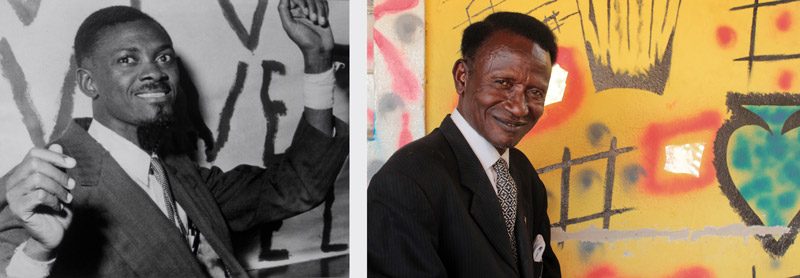

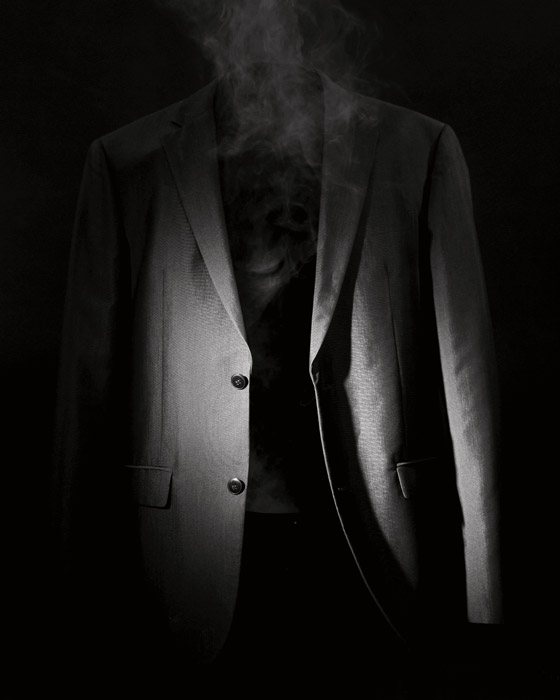

Although the exhibition opened on a time of contemplation, with the manuscripts of Timbuktu magnified through the gaze of Seydou Camara and a series of self-portraits by Sihem Salhi titled Le temps de mes prières, investigations of a present haunted by its past were evident in a great number of works, notably those that united archival and present-day images. In Tarz (which means “embroidery” in Arabic), Héla Ammar weaves together with a red thread different fragments – personal or collective – of Tunisian history marked with the seal of the revolution. In a series of diptychs titled Une vie après la mort (which received an award from the Encounters jury), Georges Senga evokes the memory of the icon of Congolese independence, Patrice Lumumba, literally embodied by an old teacher from Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

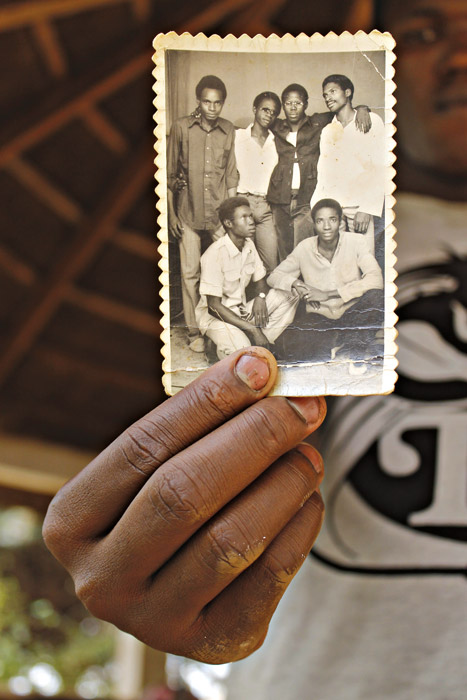

Gelatin silver photography – the photography of our childhood memories – was also featured in the pan-African selection. Lebohang Kganye, who received an award for her double project Her-Story and Heir-Story, immerses us in her family history through a subtle play on photographic superimpositions. In a reconstruction of a checkerboard-themed photography studio décor, Ibrahima Thiam pays tribute to the ritual of the portrait and its history in Senegal, whereas Moussa Kalapo (Mali) presents moving portraits, marked by the passage of time, that have become talismans in the hands of their owners. Finally, seeking to revive our silver-based sensations away from the lights, George Mahashe offers visitors an opportunity to handle slides on a light table by using a weaver’s glass and to develop images on photosensitive paper in an improvised darkroom, thus presenting a work on the colonial archives of his country, South Africa, that is both reflective and interactive.

Among the discoveries were the Algerians Lola Khalfa, Youcef Krache, and Nassim Rouchiche, all of whom address subjects that, though well anchored in reality and its difficulties (marginal environments, migrants), offer a black-and-white vision that is both metaphoric and dramatic, worked in shadows, transparencies, reflections, and blurs. Moroccan artist Youssef Lahrichi, in his Rêveries urbaines, let us touch with our fingers the infinite possibilities of self-fiction. These trends taken on by the new generation indicate that the traditional expression of reporting – that of image truth – will be less and less present in succeeding editions of the Bamako biennale.

Another sign of the times is the ever-increasing importance accorded to artists using video, such as the American Coco Fusco and her sublime La Confesión, inspired by the work of the Cuban poet Heberto Padilla. There is also the work by South African artist William Kentridge, which was on display at the Mémorial Modibo Keita beside that of another major artist, Syrian-Armenian Hrair Sarkissian, who explores the uncertainties of our times. A number of video works also received awards during the biennale, including those by Simon Gush (South Africa, Jury Prize, tied with photographer Lebohang Kganye) and by Em’kal Eyongakpa (Cameroon), who received the Tierney Fellowship for his installation Be-side(s), a hybrid collage of video performance, drawings, photographs, and poems. The growing presence of video revealed a major shortfall on the logistical front at the Bamako Encounters, however: the lack of expertise and, especially, of adequate infrastructure to present multimedia works under appropriate conditions.

There were other notable moments in the anniversary biennale. The official program presented a celebration in images of the history of the Bamako Encounters, through a retrospective exhibition titled [Re]Générations. In addition, tribute was paid to artists who had recently died: the Nigerian photographer J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (1930–2014), to whom a major retrospective was dedicated at the Musée du district de Bamako; the Malian video-art genius Bakary Diallo (1979–2014); and Thabiso Sekgala (1981–2014), whose melancholic work expressing solitude and wandering through the poetry of the banal was presented as part of the pan-African exhibition.

A High-quality, Diversified Off. Just a few steps from the Musée national, Galerie Medina was at the heart of Off, the unofficial part of the Bamako biennale, and sought to create a link among all festival-goers. Directed by the tireless Igo Diarra, the space hosted a number of “Mali-focused” events, including a symposium held both in the gallery space and at the Conservatoire des arts et métiers multimédia Balla Fasséké Kouyaté. At this event, young Malian artists had a chance to benefit from the experience of various figures from across the continent – especially Uche Okpa-Iroha (Nigeria), photographer and director of the Nlele Institute in Lagos, who was particularly generous with his time in transmitting his vision of photography to them. The recipient of the Prix Seydou Keïta (the highest distinction at the Bamako Encounters) in 2009, Okpa-Iroha was one of the stars of this edition: he was represented in the pan-African exhibition with his series The Plantation Boy, which earned him the ultimate prize once again, but also, as director of the Nlele Institute, he presented, along with photographer and curator Abraham Oghobase, the very first edition of Lagos Open Range, displaying the latest trends in Nigerian photography.

Galerie Medina also hosted a group exhibition, Peregrinate, presented by the Kenyan Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, another rising star in African photography. Cherono Ng’ok also had work in the pan-African exhibition: a tribute to her friend Thabiso Sekgala, Do You Miss Me? Sometimes, Not Always, was a mosaic of colour and black-and-white images of different sizes, representing the spaces where absence and melancholy settle.

Another bustling Off space was the Hamdallaye district, home to the association Espace Partage Photo (EPP/Djaw-Mali) directed by Emmanuel Daou (also represented pan-African exhibition) and Patrick Ertel. Espace Partage Photo, which is active throughout the year and well ensconced in the life of its neighbourhood, provided a link between the festival and the city’s residents, who, on opening night, had an opportunity to enjoy an exhibition on the walls of the neighbourhood lit by flashlights.

Among the high points of Off was the discovery of a new generation of Ethiopian photographers, presented at Galerie AD by Chab Touré, professor, art critic, and founder of the first photography gallery in Mali. And to conclude this quick tour of the horizon is my favourite Off event: the in situ photographic installation by François-Xavier Gbré and Yo-Yo Gonthier at Bla Bla Bar. Back in 2011, this hip Bamako bar had hosted the slightly crazy project of covering several walls of its terrace with photographic wallpaper. It seems that for this edition Bla Bla Bar set the bar, so to speak, even higher. And it was a total success.

The Biennale of Transmission. The re-establishment of an event of this scale after two years of hiatus took place thanks to a strengthening of local attachments and support by the younger generation present on every front, including the inclusive curatorship that Bisi Silva initiated by inviting in her young colleagues, Antawan I. Byrd and Yves Chatap. The elders who had been there at the inception were also present to share their expertise at roundtables, workshops, and portfolio critiques. And for the new artists, the Bamako dream came true again: a site of encounters and networking, the biennale is still a formidable springboard to international dissemination, as its exhibitions travel to museums and art centres in other countries.

The Malian young generation was also very present during this edition, strongly involved in advance of the success of the event. And, crisis or no crisis, photographers have continued to produce, as proved, among others, in the exhibition En connexion… organized by Chab Touré at MAP (Maison Africaine de la Photographie), on the premises of the Bibliothèque nationale. Work such as that by Dicko Traoré, known as Dickonet, a young videographer and inventive photographer who is connected to social media, gives a glimpse of all the potential of the “latest aesthetic movements that have emerged in Malian photography.”6

Thus, photography has quickly regained ground in Bamako, and the biennale essentially came back to life under the very eyes of festival-goers during the professional week from October 31 to November 4, 2015. Despite the few frustrations caused by faulty logistics regarding the installation of multimedia works and the isolation felt by monolingual photographers in the absence of simultaneous interpretation during the roundtables, bridges were built at Bamako and continue to be consolidated. The roundtables revealed, above all, how much remains to be done to make contemporary photography, in all its facets (production, dissemination, publication, reflection), a local concern, served by a discourse that is just as local. In the end, this tenth-anniversary edition of the Bamako Encounters will be seen as a moment of unifying discoveries that will enable the story to continue to be written.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 After the fall of Qaddafi in 2011, northern Mali was destabilized by a Tuareg rebellion that the Malian army, disorganized and under-equipped, was not able to quell, and this led to a military coup d’état on March 22, 2012. The north then fell under the rule of groups linked to Al-Qaeda, including AQMI and Ansar Eddine; these groups were partially dislodged in January 2013, with the launch of an international military intervention that is continuing today.

3 Would the biennale take place under normal conditions? Would journalists come, following the warnings from the French foreign affairs department, which had led the majority of Parisian media outlets not to send representatives in early September for security reasons?

4 Antawan I. Byrd, Bisi Silva, and Yves Chatap (eds.), Telling Time. Rencontres de Bamako Biennale africaine de la photographie, 10e édition (Heidelberg: Éditions Kehrer, 2015).

5 See Érika Nimis, “Lagos, Nigeria, Capital of Photography,” Ciel variable 102 (January-May, 2016): 48.

Érika Nimis is a photographer (former student at the École nationale de la photographie d’Arles en France), historian of Africa, and associate professor in the Art History Department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on photography in West Africa, including one adapted from her doctoral dissertation, Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba (Paris: Karthala, 2005). She contributes to various magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.