Climate Change in Photography and Video

Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

September 14 to December 4, 2016

By Leo Hsu

The Edge of the Earth: Climate Change in Photography and Video grapples with our changing understanding of the connection between human activity and the destiny of this planet. The title does not begin to suggest the exhibition’s ambitions, which go far beyond surveying work related to climate change. Curator Bénédicte Ramade has thoughtfully assembled artworks spanning five decades in an exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre that ponders humanity’s relationship with the world that we are making, but that we may well not survive.

The exhibition proposes that to imagine the implications of the Anthropocene, described in wall text as “the era marked by total human domination of the planet, right down to its geological essence,” we require a new visual language. Edge of the Earth seeks to move past imagery of ecological crises focused on describing consumption, waste, and the corruption of the natural world toward work that visualizes the planetary character of geologic and atmospheric changes. This aesthetic does not take humans as its scale for measurement; if anything, the people represented in this exhibition appear inert and insignificant when set against the changes that our actions have brought about. What we perceive as calamities, the earth does not perceive at all.

Julian Charrière’s Panorama, Behind the Scene (2011) adroitly comments on our anthropocentric narcissism. The video shows what appears to be a mountain glowing in warm sunlight. It’s a familiar view, recalling both Romantic painting and the lionized monoliths of North American landscape photography. But this conceit is disrupted by the artist’s appearance above the peak; what we thought was a majestic mountain is revealed as a mound of dirt. Charrière proceeds to diligently sprinkle bags of flour overthe mound, creating an alpine snowscape. Charrière’s piece recognizes the ideal of unspoiled nature as a cultural construction: we create the world that we want to see.

The works in Edge of the Earth are in dialogue with one another, in and across five thematic sections. Whereas Panorama exposes the human delusion that nature is ours to master, other pieces in the section “The Anthropocene” establish that the world is no longer under our control. There is no place for us in these landscapes: Isabelle Hayeur’s Quarternary IV (Anthropocene), a view on an uninhabitable rocky landscape, is literally nowhere, a digital collage of multiple locations and moments. Naoya Hatakeyama’s images of blasted rock frozen in midflight demonstrate speed and violence that fall outside of unaided human perception. Edward Burtynsky’s Railcuts describe unnaturally straight lines, railways carved through geologic contours. Vintage photographs from the Black Star archive at Ryerson show piles of tires and smashed cars, underscoring our delusion: waste, not wonder, is our real legacy, even as the junk is dwarfed by Hayeur’s inhospitable terrain.

Six photographs by Gene Daniels show various makes of cars in front of him on a Los Angeles freeway, interrupted by clouds of exhaust (Air Pollution, California, USA [c. 1970]). These pictures, in the “Climate Control” section, visualize pollution at ground level, but hung across from Hicham Berrada’s video of unfurling blue smoke, Celeste (2014), and Nicolas Baier’s endless fields of black clouds, Réminiscence 02 (2013), the car exhaust is just a puff. And although human influence on biomes may have once seemed exceptional, as illustrated by photographs of the effects of mercury poisoning at Minimata in the “Breaking Nature” section, it is now normalized and pervasive. Mishka Henner’s satellite images – Oil Fields (2013) – display the industrial logic with which resource extraction rewrites the landscape, referring back to Burtynsky’s railcut photographs. Brandi Merolla’s Fracking Photographs (2013) are cartoonish stagings of fracking issues featuring toys that look more angry than playful. The “Humanature” gallery addresses the human manipulation of what, until recently, was thought of as entirely nature’s domain; in Adrian Missika’s video Darweze (2011), what appears to be an active volcano is in fact a methanefilled crater in Turkmenistan, ignited by a natural-gas company in 1971 and burning ever since. The “Under Pressure” section is a magnifying glass on our small lives, occupying the corner of the gallery farthest from Charrière’s video. From that corner to this, there have been few people in any of the pieces, but here they are suddenly present. We see Joel Sternfeld’s photographs of the frustrated, exhausted delegates at the 2005 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. In Gideon Mendel’s portraits, flood survivors stand in water at their homes: Jeff and Tracey Waters, Staines-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK (2014) is an update of Grant Wood’s American Gothic – humble, surviving, making do.

In her catalogue essay, Ramade offers that she wanted to create a sense of anxiety in the audience, to incite curiosity and engagement. To do this, she juxtaposed familiar activist positions with less explicitly didactic ones, to provoke new ways of seeing. But the breadth of the pieces prevents us from seeing a clear “before” and “after”; the works play off of, and build upon, one another, and the exhibition feels more organically expansive than contrastive. Still, Ramade’s message comes across clearly, thanks to the Black Star images, which feel as though they come from another world – one where we did not yet realize what we were capable of.

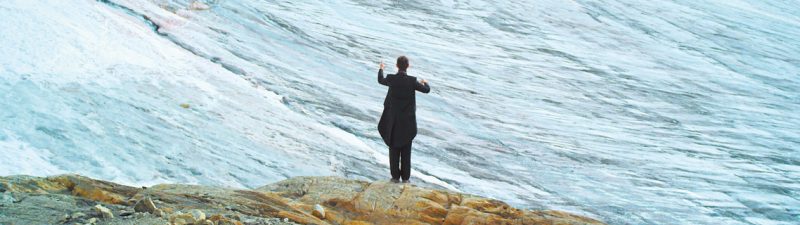

The first and last piece that a visitor sees, in the RIC entryway, is Paul Walde’s Requiem for a Glacier (2012–14), video documentation of a pilgrimage by fifty musicians and singers to perform, on British Columbia’s Jumbo Glacier, an oratorio that incorporates temperature data in the area and a Latin translation of a press release announcing a resort project. This piece, which contributed to the cancellation of the development project last summer, acts as a counterpoint to nearly everything else we have seen: at a scale that includes both humans and nature, it speaks to the possibility that our path may be corrected. In the scheme of things, this may be a small vanity, but it eases our way in and out of the anxieties of the rest of the exhibition.

Leo Hsu is a writer, educator, curator, and photographer based in Toronto and Pittsburgh. He is a regular contributor to Fraction Magazine online, was formerly a newspaper photographer, and holds a PhD in anthropology from New York University.

leo-hsu.com.