[Winter 2017]

By Pierre Dessureault

For ten years, Robert Walker has been working on a project called Hochelaga-Maisonneuve: Observations and Recollections. The subtitle conveys the two aspects of his approach. Observation is involved with things seen and corresponds to the spontaneous aspect of his undertaking, conducted without a pre-established plan. Above all, as in his previous works, Walker is a flâneur who goes where his eye takes him. The other aspect has to do with memory. This neighbourhood is where Walker was born and lived a good part of his life. Familiarity becomes, in a way, the guide for his wanderings through these districts tinted with memories.

In a layout for a book1 produced in 2013, Walker grouped his images in four chapters, presenting loci of interest that stood out in the mass of accumulated photographs: public buildings, churches, and the botanical garden; industry; street life; and history on a movie set. The images grouped together this way and organized in a coherent whole paint a complex portrait of the neighbourhood, in which Walker’s depth of vision and personal choices are obvious. The overall impression that emerges from this vast “work space” is that of a once-prosperous neighbourhood, as evidenced in the public buildings showing social progress for a rising working class – until the industrial decline in the second half of the twentieth century sounded the knell for such utopias.

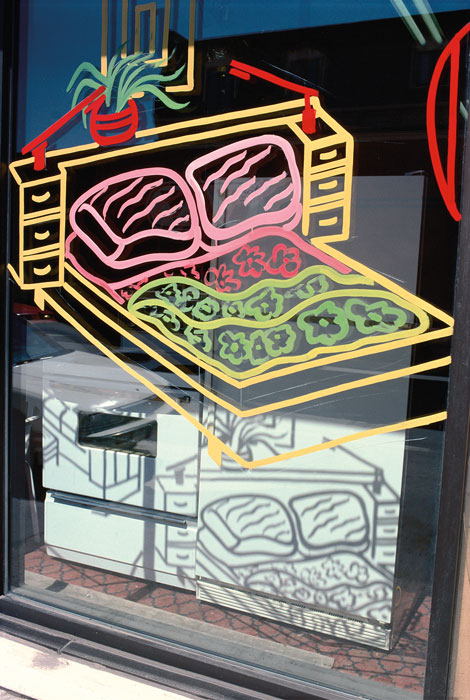

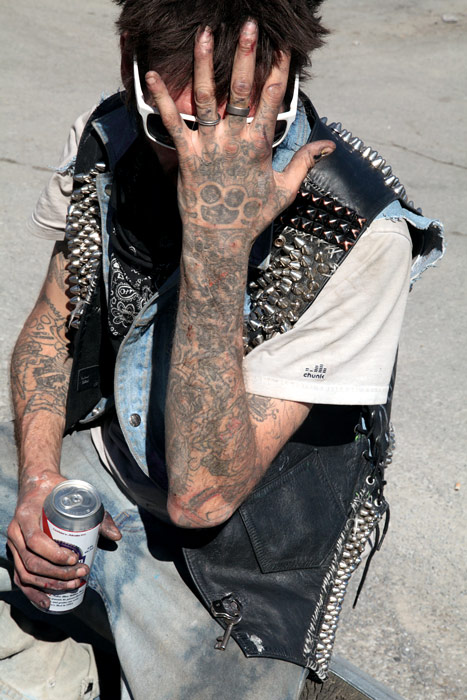

Today, Hochelaga-Maisonneuve presents all the signs of a district marked by deep social fractures. Boarded-up storefronts covered with graffiti, industrial vestiges, gaudy shop windows, and buskers are as typical of neighbourhood life as are the Maisonneuve market, the Olympic Stadium, and the churches. Walker neither establishes a hierarchy nor takes a position: he observes and captures the present. He could easily have been described in these words by James Agee, who collaborated with Walker Evans (a photographer with whom Walker identifies) on the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a classic of the documentary style: “I am interested in the actual and in telling of it, and so would wish to make clear that nothing here is invented. The whole job may well seem messy to you. But a part of my point is that experience offers itself in richness and variety and in many more terms than one and that it may therefore be wise to record it no less variously.”2

Another characteristic shared by Walker and Evans is a passion for vernacular culture – the set of identifying traits revealing a popular wisdom resulting from a unique relationship with the environment and the organization of activities in living space, the tools and manners that structure daily life. Walker obviously takes pleasure in detailing the abundant imagery of motorcycles, skulls and skeletons, effigies of Marilyn, and film stars fighting for public space with a motley multitude of ads and displays. Like a Rosenquist, his art consists of discerning these expressions of the social imagination and blending them in his images: his bold framings fragment icons to highlight certain parts, bring them into confrontation, and integrate them into a photographic collage.

Although Walker defines himself as a street photographer in the tradition of Friedlander and Winogrand, who also favoured unrehearsed and instantaneous picture taking with unusual angles that fracture the pictorial space and telescope the planes, he does not in any way deny his training as a painter and visual artist. Therefore, in his photographs colour not only strengthens the realism of the documentary description but structures the images by creating strong chromatic contrasts and juxtaposing vast areas of saturated colour. This very particular approach to the image and its construction is one of the cornerstones of Walker’s visual vocabulary.

Generally, much is made of the truth associated with the practice of documentary photography. In Walker’s case, this truth doesn’t really reside in a respectful distance from the subject and satisfaction with recording a wealth of details. Nor does it reside in an activism that would put photography in the service of social progress. Walker positions himself as an observer whose eye is enhanced by his fairly intimate knowledge of the neighbourhood, its history, and its evolution. Onto this observer is grafted the photographer, with his wisdom and knowhow, who models his vision of things developed over time through his training as a painter, his taste for pop art, and his admiration for the work of predecessors who, each in his own way, testified to their times in their practices.

Certainly, given the range of descriptive practices, formal vocabularies and personal stances highlighted in various projects about Montreal, it seems that the documentary genre is above all a question of intention: “Ultimately, it is intended that this record and analysis be exhaustive, with no detail, however trivial it may seem, left untouched, no relevancy avoided, which lies within the power of remembrance to maintain, of the intelligence to perceive, and of the spirit to persist in.”3 The rest is a question of vision and style.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001), 216.

3 Ibid., p. 10-11.

Robert Walker was born in Montreal, where he studied painting at Sir George Williams University. In the mid-1970s, he developed a keen interest in street photography. He moved to New York City in 1978, and his first book, New York Inside Out, was published in 1984. He has exhibited widely in the United States, Canada, and Europe. His images have appeared in many prestigious journals and books.

Pierre Dessureault is an expert in Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized some fifty exhibitions, published catalogues, contributed to books, and written a number of articles on photography. Since his retirement, he has devoted himself to studying international photography in a historical perspective and, reviving his early interest in philosophy and aesthetics, to exploring in greater depth the theoretical approaches that have marked the history of the medium.