[Spring-Summer 2017]

By Franck Michel

The relationship with the

landscape always involves

emotional sensitivity to

the work before gazing at it.

(our translation)

David Le Breton, Marcher (Éloge des chemins et de la lenteur)

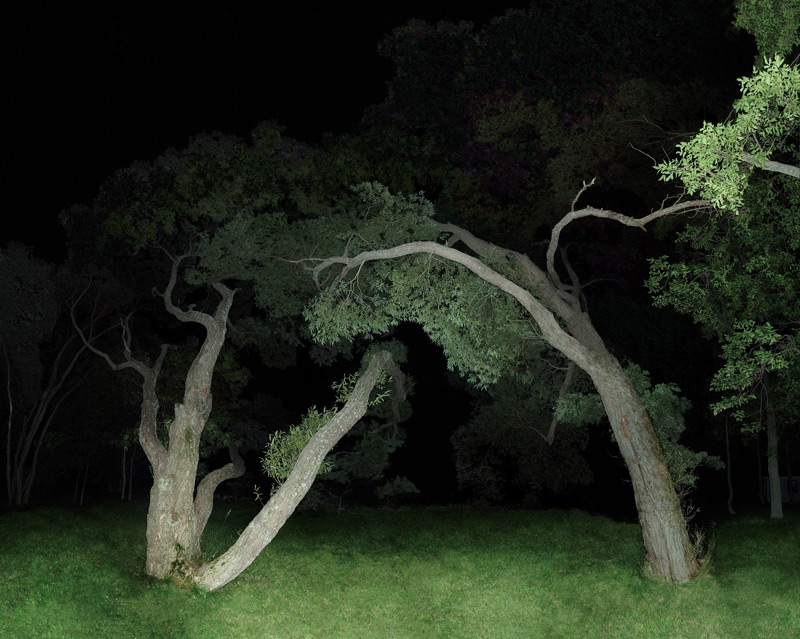

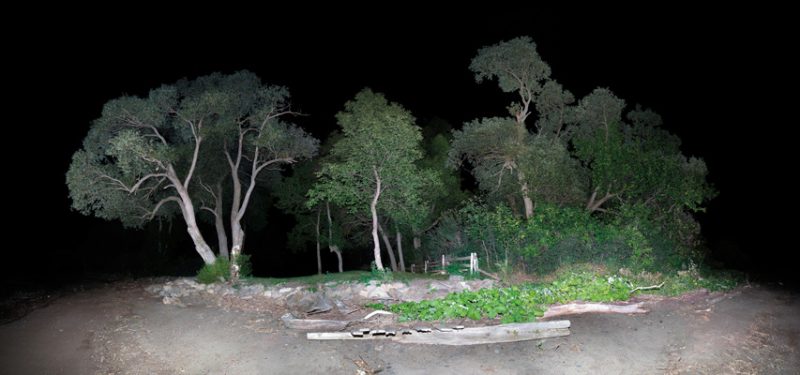

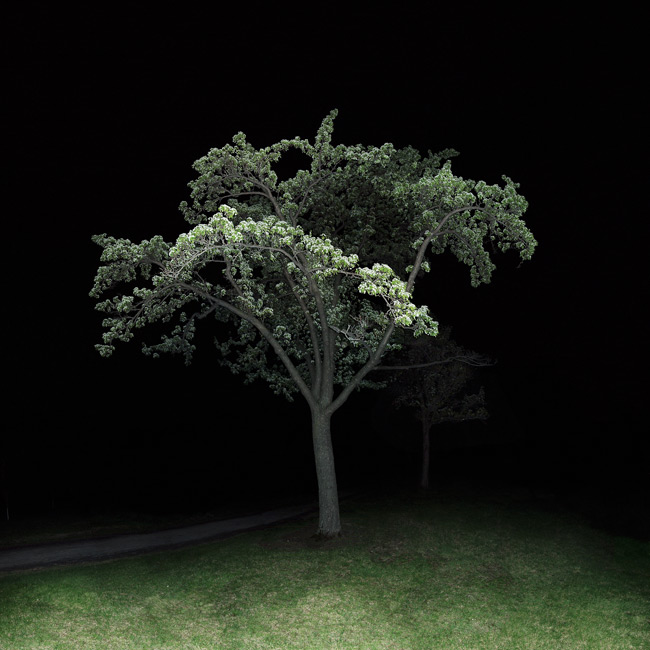

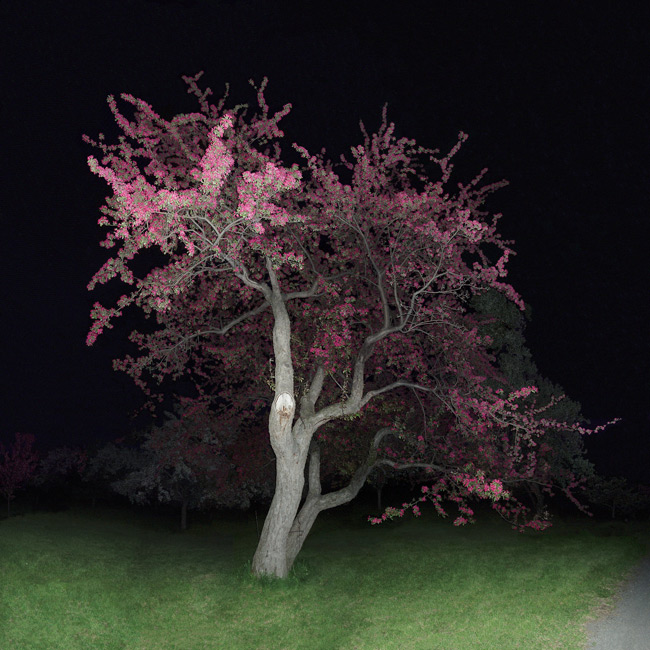

For more than ten years, Jocelyn Philibert has been photographing trees at night. This near-obsession was triggered during a summer spent in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, on the bank of the St. Lawrence River. Having just acquired a small digital camera, he decided to go out and explore the vicinity of his cottage, photographing everything around him, after the sun went down. He was particularly fascinated by a picture of a willow – and by how simple it was to use a digital camera. Known mainly as a sculptor, he now began to develop a primarily photographic approach based on nocturnal landscapes dominated by figures of trees. The resulting works have been organized into a number of series: Des arbres dans la nuit (2006), Sites (2007), Capter tout (2008), Panoramas (2009), Transparence (2010), Illumination (2012), and Intrusion (2014).

The tree, the archetypal pillar in nature, is an omnipresent symbol – a metaphor for life, wisdom, vital power, and longevity, and, more recently, an emblem for ecological struggles. Whether romantic, mystical, political, or formal, the figure of the tree is found throughout art history. Many photographers, like painters and sculptors before them, have devoted entire bodies of work to it – Eugene Atget, Harry Callahan, Lee Frielander, Edward Weston, and Arnaud Class, to mention just a few. Having studied this long tradition and its masters, Philibert gradually developed an unusual patient, meticulous approach, involving a number of temporalities and steps of attentive manipulation.

By day, Philibert surveys the Quebec countryside, mainly the Côte-du-Sud (Chaudière-Appalaches) region, on foot, by bike, or by car, scouting locations to take pictures at night. He isn’t looking for the spectacular or the picturesque; he is interested in banal sites, common species of trees, undergrowth, places that the eye passes over. Country roads and highways, though rarely shown in his images, are always there, an indispensable condition for future image production: he uses them to discover the landscape by day and return to photograph it at night. The location-scouting phase, a key aspect of his approach, involves multiple trips of varying lengths through the countryside. This experienced spatiality combines the routes taken, the body of the walker or cyclist in action, the surrounding environment, and the emotional dimensions awoken during the journey.1 During Philibert’s nocturnal travels, this spatiality is modified by how the night transforms the senses.

When he returns at night to the places earmarked in the light of day, Philibert finds himself alone, outside of time, immersed in a night-time landscape that is both soothing and harrowing, to the accompaniment of the rustling of leaves and sometimes the burbling of a stream or the backwash of the river. In his wonderful book on walking, David Le Breton gives a magnificent description of this experience of the night: “One gets the sense of being a tiny creature under the infinite sky and the stars; swept up in this power, one begins to feel even more alive, no longer attached to a personal life but submerged in a sea of shapes in which one is no more than one ridiculous, emotional breath.”2 In this moment of privileged aloneness, immersed in nature, Philibert photographs the site almost frantically, accumulating numerous pictures that will later be arranged to form just one image. Plunged into darkness, he cannot choose the frames for his shots. He usually photographs by guesswork, leaving much to chance and randomness. Only the momentary lightning of the camera’s flash illuminates the landscape fragment by fragment, highlighting certain parts and leaving others in shadow.

Back in the studio, Philibert begins the slow, detailed task of arranging images. He proceeds by slight movements, using fragments of pictures to reconstruct an overall view of the site. The resulting composite image has a sense of hyperrealism and three-dimensionality. The final rendering, perfectly smooth, leaves no trace of the montage. Reconstructed in this way, the work oscillates between imaginary landscape and captured reality. Has Philibert perfectly reproduced the original site as he saw it, or believed he saw it, or has he added elements or distorted reality? In the end, that isn’t really important. Presented as stage sets on which a story may be invented, these composite photographs invite each of us to imagine our own narrative or simply to contemplate and let ourselves be enchanted by the power of the trees.

Up to recently, Philibert’s landscapes were considered to be composed essentially of natural elements dominated by the presence of trees. Having devoted a series to sites photographed on the edges of overpasses (Transparence, 2010), he introduced human-built elements into the frame, most of them vernacular architecture: cabin, old house, stone wall, street, and so on (Intrusion, 2014). These elements, evidence of human activity, reinforce the magical and unsettling atmosphere produced by the strange light and theatricality inhabiting each image. To this is added, under the effect of the flash and the exaggerated precision of the details, the imprint of a certain mysticism that somehow evokes the contemplative nature writings of the transcendentalist philosopher Henri David Thoreau.3

A landscape appeals to all of our senses, has a memory, and is composed of many strata. As Le Breton observes, it is “a superimposition of screens – or, rather, of depths that are visual, aural, tactile, olfactory, each sense mixing with the others.”4 What Philibert’s photographs, many of which are in very large format, do perfectly is to invite us to enter this depth, to “feel” the landscape, and to discover new perceptions in it. Although they don’t make an unambiguous ecological statement, their sensitivity and evocative power also remind us of the fragility of the plant world.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 David Le Breton, Marcher (Éloge des chemins et de la lenteur) (Paris: Édition Métaillé, 2012): 53. (our translation).

3 In particular, The Maine Woods, Walking, and the celebrated Walden, Or, Life in the Woods.

4 Le Breton, Marcher, 71. On the subject of landscape as experience and sensory space, see also Jean-Marc Besse, “Le paysage, espace sensible, espace public,” Meta: Research in Hermeneutics, Phenomenology, and Practical Philosophy 2, no. 2 (2010): 267, www.metajournal.org.

Franck Michel has been working in the visual arts for more than twenty-five years. He has curated fifteen exhibitions and edited a number of publications, most of them on the subject of representation of landscape in contemporary photography. He was curator of the 2016 and 2017 editions of La Rencontre Photographique du Kamouraska. In 2015, he received a Canada Council for the Arts curatorial grant to conduct research on landscape as sensory space.

Over the last twenty-five years, Jocelyn Philibert has presented his work in individual exhibitions at La Chambre blanche (Quebec City, 1991), Galerie Clark (Montreal, 1996), Circa (Montreal, 2000), VU Photo (Quebec City, 2006), Galerie Verticale (Laval, 2008), Pikto Art Gallery (Toronto 2011), and Centre d’exposition de Rouyn-Noranda (2012). His work has also been in numerous group shows and are in the collections of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Musée National des Beaux-Arts de Québec. He lives and works in Montreal. jocelynphilibert.com