[Winter 2018]The exhibition Gabor Szilasi: The Art World in Montreal, 1960–1980 is being presented at the McCord Museum, Montreal, from December 8, 2017 to April 8, 2018.

By Zoë Tousignant

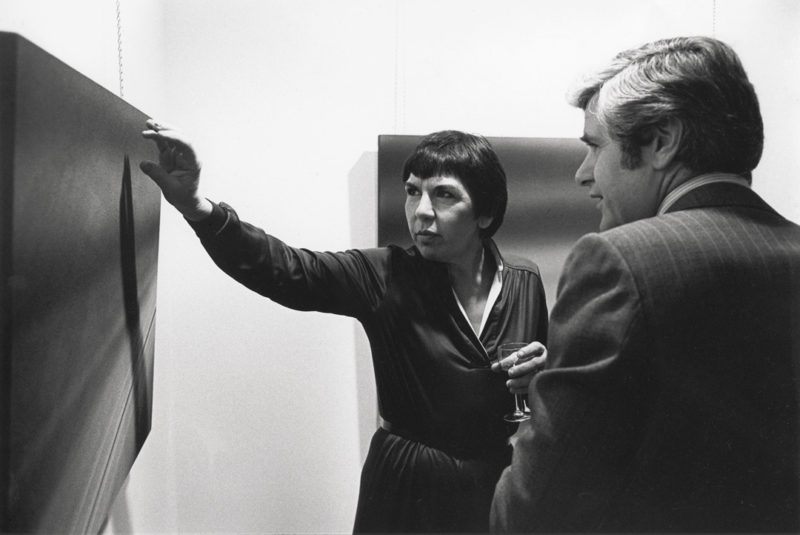

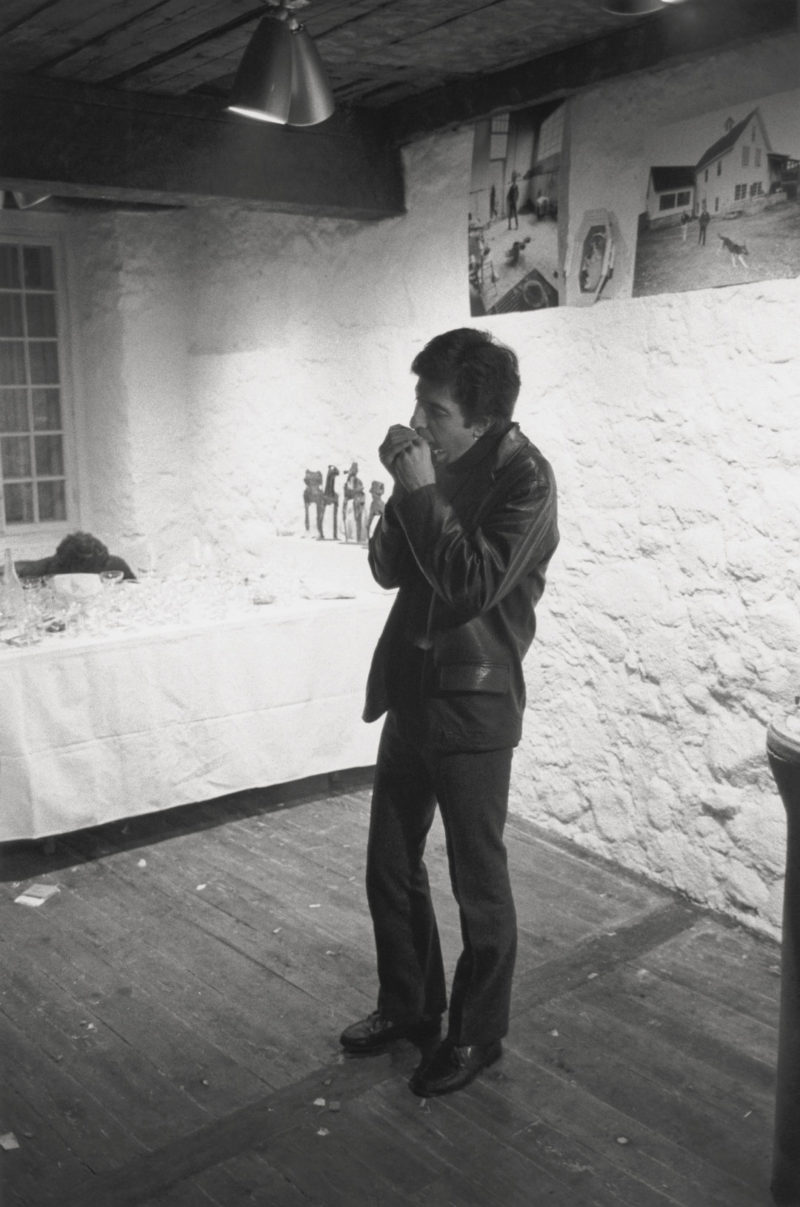

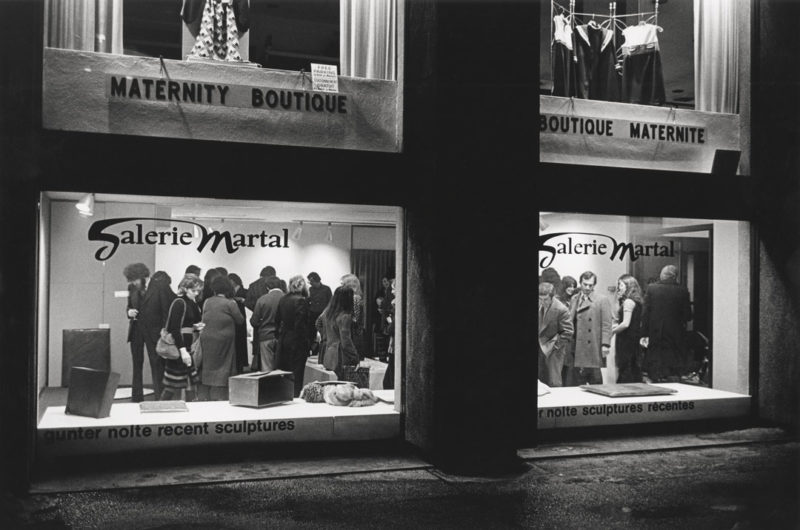

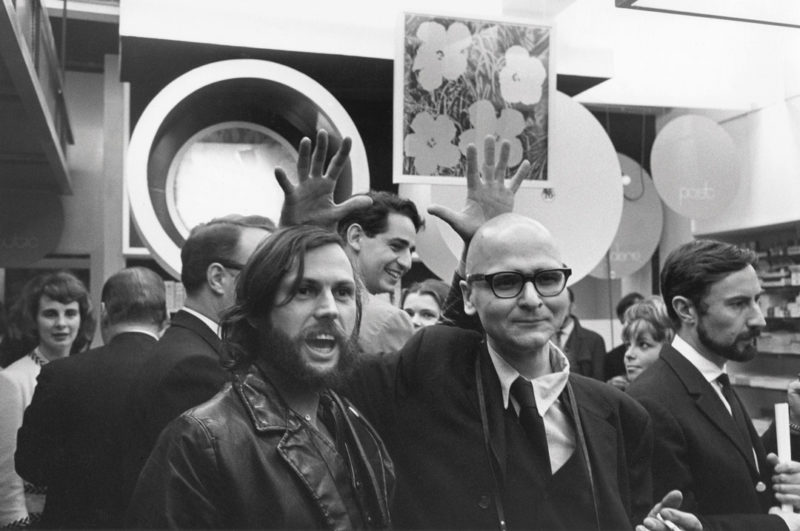

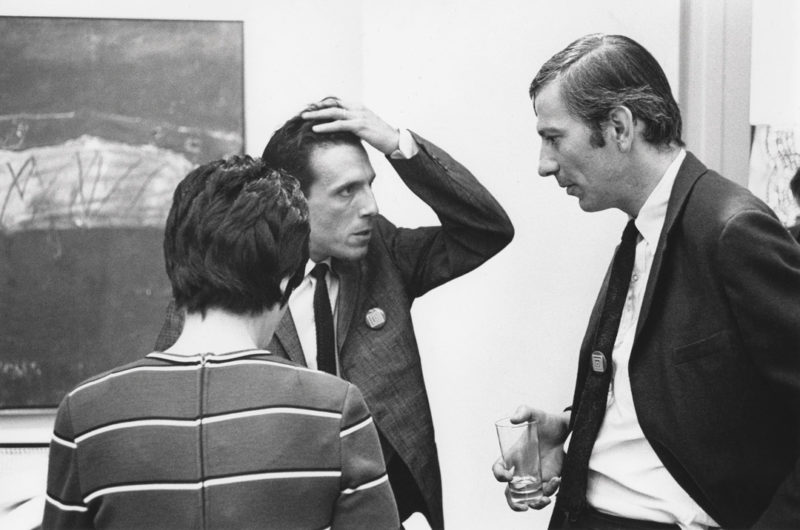

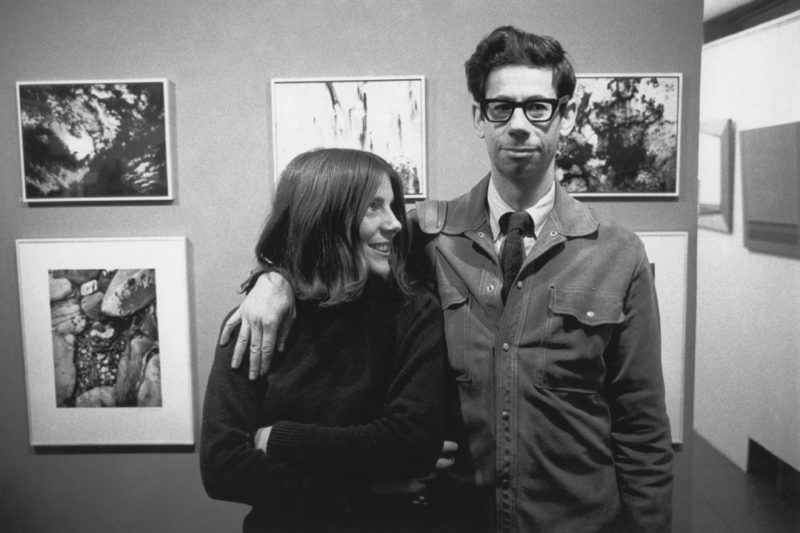

Photographer Gabor Szilasi was born in Hungary in 1928 and immigrated to Canada in 1957. Soon after settling in Montreal, Szilasi began to photograph the many art openings that he and his wife, artist Doreen Lindsay, regularly attended. Over the next few decades, he produced an extensive photographic record of some of the individuals and sites that have shaped the history of art in Quebec and Canada. Although Szilasi continued to document art openings until the early 1990s, the photographs he took in the 1960s and 1970s form the greater part of the corpus. Shot entirely on 35 mm film (primarily using a Leica M4 camera with a 35 mm Leitz Summicron lens) and consisting of some 3,600 negatives, this important body of images is, of all the photographer’s projects, the most closely aligned with his personal life. It captures his initial integration into Montreal’s art world – a world that would become his base and his home.

Aside from a few exceptions that were included in Szilasi’s 2009 retrospective exhibition The Eloquence of the Everyday,1 these images have never been publicly displayed before, even though Szilasi has wanted to do something with them since the 1990s (or roughly since his practice of photographing art openings ceased). Lindsay, too, has long been hopeful that they would one day be shown; she has been acutely aware of their significance, both within the larger scope of Szilasi’s practice and as testaments to an important dimension of artists’ lives. In the visual arts, openings offer artists a rare opportunity to leave the solitude of the studio and come together. Executed in parallel to his many portraits of artists and his professional commissions to document artworks, Szilasi’s images of openings offer visual – and unique – proof that during the period covered a sense of community existed in Montreal’s art world.

As fate would have it, it has taken another twenty years or so for a substantial selection of the corpus to be printed and exhibited. The distance between the taking and the showing of the photographs (the early ones are now almost sixty years old) has meant that they have accumulated value as historical documents. Because most of the galleries represented no longer exist, and because many of the people portrayed are no longer alive, these pictures serve a memorial function that would have been far less crucial had they been shown earlier. That Szilasi is now ninety years old is also significant: what he has essentially done is revisit an archive that is filled with his friends and acquaintances, several of whom are among the deceased. A personal reflection on death and the passage of time was an inevitable part of this revisiting. For him, the archive cannot be disassociated from his life.

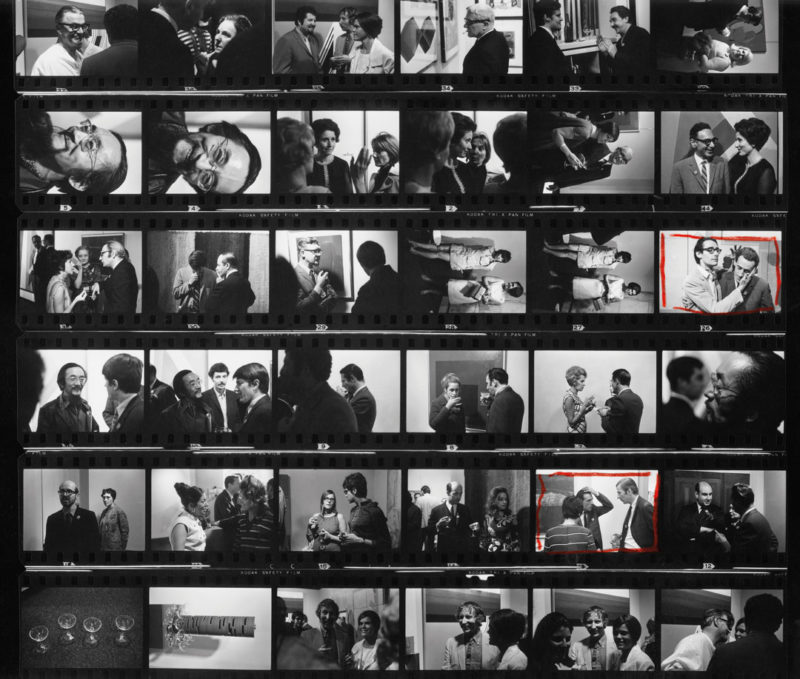

Szilasi asked me to work with him on this project because he felt that someone younger might be able to provide a generational distance that would allow for a more objective take on the corpus. He wanted help with the selection of images because he worried that left alone he would simply be drawn to his friends and overlook all the other good pictures. But the reality ended up being rather different (sorry, Gabor). As I quickly discovered on my first look at the one hundred or so contact sheets that compose the archive, these images are also of great personal significance to me. As an artist’s daughter who grew up in Montreal’s art world in the 1980s, I was familiar with many of the individuals who people the archive, for they played starring or supporting roles in the affective landscape of my childhood. My parents, Claude Tousignant and Judith Terry, would take my sister, Isa, and me to many of the openings they attended – they constituted family outings. In my memory, openings were entertaining, joyful events at which I was introduced to a lot of smiling, slightly drunk people. My parents were always happy to see their friends, so I was happy too.

But while, on one level, the familiarity I felt with Szilasi’s archive was due to first-hand experience, on another, it was based on handed-down knowledge: the images represent a time that, though it predates me, I have heard a great deal about. For as long as I can remember, my parents have been fond of recounting, with only minimal prompting, crazy art-world anecdotes set in the 1960s and 1970s, often at openings. For me, seeing Szilasi’s archive for the first time was both strange and elating, since all of a sudden the stories I had been told my whole life became photographically real. It felt as though I had unearthed a secret family album that had been stashed away for years in some obscure attic. Scouring the contact sheets, I found the illustrations of a history that up to that point had been primarily oral.

It became clear that it would be very difficult for me to work on this project while maintaining a detached, scientific point of view on the corpus. Such an approach would have felt disingenuous, as though I were concealing my personal experience for the sake of a notion of objectivity that I do not particularly believe in. More importantly, it seemed to me that if Szilasi’s photographs had this kind of strong emotional impact on me, there was a good chance that they would have a similar effect on others. So the work became about finding strategies to integrate the emotional as a productive component of curatorial practice. The idea was to embrace – and take seriously – a dimension of photographic experience that is nostalgic, tender, even sentimental. Photographs have an uncanny ability to stir the emotions: this is well known, and many have written about it. Yet allowing the emotional to enter the gallery space and to “taint” the reading of photo- graphs that could, without discounting the photographer’s individual authorial voice, have been viewed as pure documentation seems less commonplace.

Szilasi’s images are important socio-historical documents of a time and a place, but they are also symbols of personal histories – not just for him, or for me, but for a whole community. They represent a shared personal history. Until now, the Montreal arts community of the period was unaware that images illustrating its anecdotal histories existed. Some who were present at the time remembered that Szilasi was always at art openings with camera in tow, but very few imagined that he was amassing so substantial an archive. Save for the select few who had a chance to glance at it or had at least heard about it, the archive, dormant in the photographer’s home for over fifty years, was entirely unknown. But Szilasi is nothing if not generous, and with this project he is finally giving back an important body of work to the community whence it came.

Zoë Tousignant is a historian of photography specializing in Canadian photography. She currently works as an assistant curator with the McCord Museum’s Photography Collection and as a curator at Artexte.

Over the years, Gabor Szilasi has produced a remarkable global portrait of Quebec as a society and Montreal as a city. His work has been exhibited and acquired extensively in Canada and abroad, including two retrospectives organized by VOX and by the Musée d’art de Joliette. Born in Budapest in 1928, he has lived and worked in Montreal since 1958. He taught photography at Concordia University in Montreal from 1979 to 1995. He was a recipient of the Prix Borduas for his career achievement in 2009.

[Full issue available here : Ciel variable 108 – GOING PUBLIC ]

Purchase this article