[Spring-Summer 2018]

By Jill Glessing

Movement is elemental to existence. Since we made our slow crawl from sea to land we’ve been “on the road” seeking better environments. But another force – territorialism – counters that drive and stems our free flow with walls, great and small. Modernity brought increasing privatization of space through land enclosures, private property, nation-states. Surges in border-wall construction came with the post–Second World War geopolitical remapping and later, paradoxically, in response to relaxed trade barriers and increased capital mobility under globalization. Wall construction proliferates still, as wealthier nations seek to stop migrants fleeing war, poverty, and the effects of climate change.

One of the most contested instances in modern border history is the Cold War construction that sliced through a city’s body politic – the Berlin Wall. Built in stages by East Germany starting in 1961, its iconicity only increased with its 1989 destruction, its fragmentation, and the circulation of those fragments outside Germany. To many in the “free world,” those roving concrete fragments – from large slabs to chips – signalled the supremacy of liberal democracy and capitalism, victorious over a failed communism, a moment infamously described by Francis Fukuyama as the “end of history.” Their rich symbolism making them ripe for ideological and commercial exploitation, Wall fragments now function for commodification, tourism, personal memory, state diplomacy, ideological propaganda, art collection, and eBay entrepreneurship. Ronald Reagan’s call, in 1987, to “Tear down that wall!” seems, in retrospect, a demand for new commodities, as over two thirds of the Berlin Wall are now in the United States. The country most antagonistic to the Soviet project was also the quickest to capitalize from it.

Freedom Rocks: The Everyday Life of the Berlin Wall – Blake Fitzpatrick and Vid Ingelevics’s long-term collaborative documentary art project – dwells on that rich architectural and ideological history. Since 2003, the artists, as archaeologists and cultural anthropologists, have worked to extend the Wall’s history beyond 1989. Their massive archive of photographic and video documentation of the Wall in Berlin and in North American locations focuses on the everyday as much as the monumental. They draw on their “art data base” to create installations that open up multiple perspectives on that cultural history.

New compilations from Fitzpatrick and Ingelevics ’s archive were recently presented at two Toronto venues. In Prefix ICA’s The Labour of Commemoration,1 a large three-channel video installation of the same title (2017) focused on Berlin’s twenty-fifth commemorative celebration of the fall of the Wall. The randomly organized collaged footage, collected by the artists as they bicycled through the city, tracked the mundane processes of setting up, the day itself, and the post-party clean-up. Any potentially grand moments, such as Gorbachev’s stage appearance, blend in with the minutiae, such as the transport by workers of a Wall slab freshly painted with a portrait of that same Soviet leader, to its location in front of a high-end hotel.

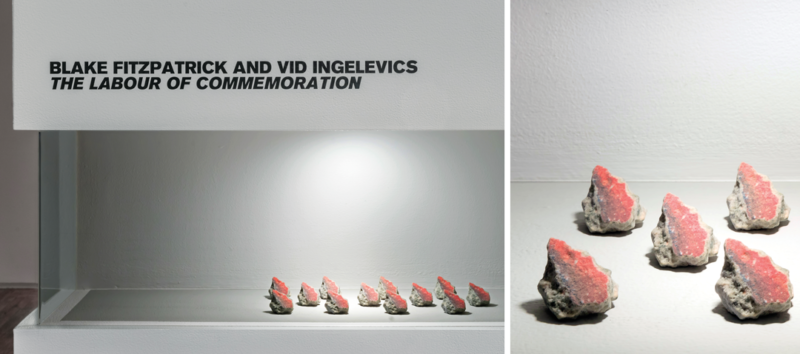

An important sector of the Berlin Wall economy has been the commodification of small pieces for souvenirs and mementos. Mistakenly thought to be more authentic, those bearing graffiti paint are more popular. To move the less desirable grey cement stock, marketers paint them, and to further expand the market, they manufacture new relics. Drawn from the artists’ collection, rows of fake fragments, identical in size and colour, were arranged in neat rows in a vitrine (3D printed Berlin Wall Souvenir(s), 2017).

We can’t consider the topic of border barriers without thinking of today’s controversial examples: Israel’s “Apartheid Wall” controlling Palestinian movement; the Spanish barricades at Ceuta and Melilla built to prevent African migration; and President Trump’s proposed extension of the Mexico-United States border wall to keep out “criminals, drug dealers, and rapists.” In relation to this last example, the installation Friendship Park (2014) included three colour photographs of the barricades dividing Tijuana and San Diego. On a small monitor, a short video documented a man speaking about his separation from his Californian community. Peering through the thick web of metal fencing, he noted the irony of the park’s name and the unfriendly removal, on the U.S. side, of the friendship commemoration plaque.

Functioning differently from the small Wall chips valued as keepsakes and souvenirs are the full slabs, their greater price tag and monumental size making them more suited for signalling economic or political status. In The Mobile Ruin at the Harbourfront Centre,[2] a large collage of twenty colour photographs stretched crossword style over one wall (2017) shows their various, strange, and often roving existence throughout North America.

One image refers to the marketing of Berlin Wall slabs in the United States. The New Jersey contractor, Joe Sciamarelli, a critic of communism proud to profit from its collapse, procured distribution rights for those potent cement symbols. One photograph shows two slabs, ingloriously waiting to be unloaded for the right price, lying wrapped on a flat-bed truck behind what appears to be a suburban garage. Another image evidences Sciamarelli’s marketing skills: tourists pose by a slab that he persuaded Ronald Reagan to purchase for his Presidential Library in California. Yet another image shows the Wall as emblem of free enterprise and the tight relations within international business. Lined up near the slab installed at the Microsoft Conference Center, presented to Bill Gates by Daimler-Benz AG, unsuspecting teens, perhaps on a class outing, absorb its ideological values.

Five vertically arranged images chart the changing values of graffiti painted slabs owned by New York developer Jerry Speyer: their outdoor installation on Madison Avenue; the same location after their removal; their presence in a warehouse where conservators worked to stabilize their eroding surfaces; and their return to and installation at their initial location, but now inside a protected lobby. The series asks us to consider the puzzling semiotic trajectory of a practical cement government infrastructure morphing into an aesthetic high-art object.

Opposite the collage, a large mural shows cement Wall shards of different colours photographed against a deep black ground, making them appear as celestial bodies floating in an abyss of lost past. The image thus goes beyond the fine tracking of minute historical detail and political scrabble, suggesting a more metaphysical contemplation of history. The archival instinct of documentation and collection helps us stabilize the past and resist the dissolution of material artefacts – those prompts and proofs of memory – and their free dispersal through open space.

Such provocative questions lie at the heart of Freedom Rocks. Through the ongoing gathering of images and materials connected to that critical historical moment, and the presentation of them in following decades, audiences are asked to measure their meanings anew, in relation to our changing perspectives.

2 The Mobile Ruin, at the Harbourfront Centre, from September 23 to December 24, 2017. The Mobile Ruin is part of the project conceived by Yvonne Lammerich and Ian Carr-Harris titled Voices: Artists on Art.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.

Blake Fitzpatrick is a Toronto-based photographer, curator, and writer. He has shown his work in solo and group exhibitions in Canada, the United States, and Europe. His curatorial projects examine the work of contemporary artists who respond to war and social conflict. His writing has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. Fitzpatrick holds the position of professor and chair in the School of Image Arts, Ryerson University.

Vid Ingelevics is a Toronto-based artist, writer, and independent curator. His artwork has been shown in solo and group exhibitions across Canada, the United States, and Europe. His writing has also appeared in numerous art publications. He is currently an associate professor at Ryerson University, where he teaches in photography and in the Photography Preservation and Collections Management and Documentary Media programs. freedomrocks.ca

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Blake Fitzpatrick and Vid Ingelevics, Freedom Rocks: The Everyday Life of the Berlin Wall – Jill Glessing, The Mobile Ruin and The Labour of Commemoration ]