[Fall 2018]

An interview by Jacques Doyon

Louise Déry holds a PhD in art history and has been director of the Galerie de l’UQAM (Université du Québec à Montréal) since 1997; previously, she was director of the Musée régional de Rimouski and curator of contemporary art at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. She has organized exhibitions by Canadian and international artists presented in Quebec and Canada, Europe, the United States, Mexico, and Asia, and she was curator of the Canadian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007 (David Altmejd). In 2007, she was the first winner of the Hnatyshyn Foundation Award for Curatorial Excellence, and in 2015, she received the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. A member of the Royal Society of Canada, she was made a Chevalier des arts et des lettres in France in 2016.

JD: How did you come up with the plan to host the exhibition Uprisings in Montreal? Why did you feel it was relevant to bring the exhibition here? Was the Galerie de l’UQAM a partner in the project from the beginning?

LD: Usually, collaborations are born of intellectual and amicable alliances and from the desire to share ideas and bring them alive. Participation by the Galerie de l’UQAM in the Uprisings project conceived by Georges Didi-Huberman was therefore, from the start, an affair between friends that goes back to the 1990s. The publication of Didi-Huberman’s book Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (Éditions de Minuit, 1992) was of great interest to a historian of “exhibited art” such as me. Didi-Huberman then published many books that were fundamental to the history of these disciplines, and that were widely read and shared in Quebec academic, museum, and art circles. As he became better known to and appreciated by a broad community of art historians and philosophers in Montreal, he came here several times to participate in conferences and seminars, and I got to know him through one of these events some twenty years ago. When he returned to UQAM in 2014 to receive an honorary doctorate, he talked to me about Uprisings and his desire to present this ambitious project at the Galerie de l’UQAM. I quickly expressed my strong interest in exploring the possibilities of hosting this incredible transdisciplinary “montage” on political upheavals that have caused population uprisings. The director of Jeu de Paume, Marta Gili, contacted me in early 2015, at Didi-Huberman’s request, as plans for an international tour of the project were beginning to take shape. That’s how our collaboration began.

JD: Can you tell me about the general outlines of Uprisings (in terms of intentions, content, and structure)? What excited you about it? What parts of its original content will we see in Montreal? Was the idea of touring the exhibition, with hosting partners contributing to the project with sections specific to their respective regions, part of its original concept?

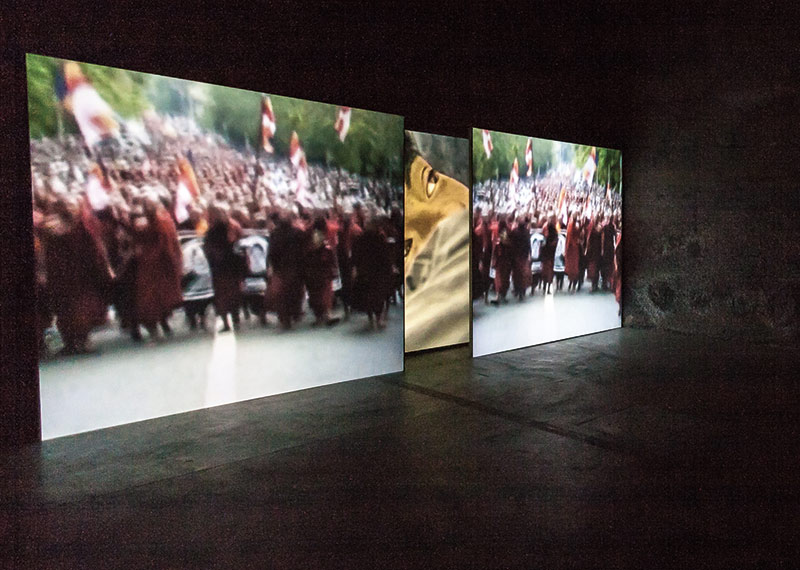

LD: I must say, I loved the project from the start. In formulating a narrative of the struggles that have marked history through works and images with diverse statuses (artworks, documentaries, films, manuscripts, printed works, and so on) and focusing on the theme of collective emotions associated with political events involving struggling masses, Didi-Huberman extended the unique research method instigated in his famed project Atlas. Comment porter le monde sur son dos? (presented in Madrid, Karlsruhe, and Hamburg in 2011) that led him to work in the “eye of history.” At the time I became involved in the project, he had compiled a list of more than 450 works, films, and documents exploring the representation of peoples in movement. This presented me with a few challenges: imagining Uprisings in the context of a university gallery devoted to contemporary art; finding an exhibition partner that could provide us with spaces so that we could avoid adulterating the project by forcing too drastic a reduction of it; to undertake a dialogue with the curator so that he would be open to my suggestion, which I would call an imperative, to include Quebec and Canadian content, which would no doubt mean that we’d have to sacrifice some works from the original selection. With regard to the first challenge, I can emphasize that the Galerie de l’UQAM periodically steps outside its editorial guidelines for projects that open up to interesting perspectives on research and creation, if it is a question of associating historical works with current production or academic subjects with art projects. I met the second challenge by proposing a collaboration to the Cinémathèque québécoise that was extremely well received given the large role played by films in Didi-Huberman’s selection. The third challenge, which was to include examples of uprisings related to the Canadian context, was received enthusiastically by Didi-Huberman, and this “condition” was quickly taken up by other partners on the tour, which requested similar adaptations. Following much discussion, Uprisings had different incarnations depending on the location (Barcelona, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Mexico City, and Montreal) – an incredibly rich prospect for a curator, who thus sees the exhibition come alive in each iteration. I would add that the tour offers about 80 percent of the content presented at Jeu de Paume; also, a number of fragile pieces were not available for circulation, so facsimiles were produced by Jeu de Paume so that the meaning of the narrative wouldn’t be compromised.

Didi-Huberman’s series of books titled L’œil de l’histoire forms the foundation for this vast exhibition project. In these publications we see how his historical and theoretical approach bears on the political and aesthetic representation of peoples. In Uprisings, he conducts a transdisciplinary exploration of the collective emotions that characterize social disorder, political agitation, rebelliousness, insurrections – in short, upheavals of all kinds. The exhibition, along with the catalogue published by Gallimard, is structured in five parts: “elements (unleashed),” “gestures (intense),” “words (exclaimed),” “conflicts (flared up),” and “desires (indestructible).” The curator had devised this first typology, admirably constructed to offer extremely rich and varied motifs that closely reflect the selection of works, with the representation of “arms [that] rise up,” “walls [that] speak up,” “books of resistance,” “vandal joy,” “mothers [who] rise up,” and “barricades [that] are erected” – examples found in the 229 works in the touring exhibition all of which were presented at the Galerie de l’UQAM and the Cinémathèque québécoise. The involvement of the Cinémathèque québécoise made it possible to host the exhibition in its premises, doubling our exhibition space and offering a program of films presented in September, October, and November.

JD: Can you describe what is in the Quebec (or Canadian) section of the exhibition? What types of works, what periods, and what media have been favoured? How have these works been integrated into the initial structure of the exhibition?

LD: I conducted research for more than a year in order to formulate proposals that could be integrated into the project while shedding interesting light on the Canadian – and, especially, Quebec – context. This work was often done informally through discussions with colleagues and friends. I drew on the support of Ariane de Blois to examine certain possibilities for subjects to cover and works to consider. Together, we targeted events as diverse as feminist, Indigenous, gay, ecological, student, racial, and labour struggles, and, without claiming to cover so vast a grouping of contexts, we did, I believe, identify numerous documents and works that dealt with our own rebellions. The Refus global manifesto, on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of its publication (1948), and an evocation of the student uprising at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal (1968) are at the heart of the exhibition.

Among other things, this gave me the opportunity to introduce some majestic works to Didi-Huberman, such as Rebecca Belmore’s The Blanket, which evokes the dark history of the British authorities passing out smallpox-contaminated blankets to decimate Indigenous populations; Mina Shum’s film Le Neuvième, which evokes the “Sir George Williams affair,” symptomatic of the racial discrimination that existed in Montreal in the 1960s; the video Nous nous soulèverons, by young filmmaker Natasha Kanapé Fontaine on Indigenous claims; and Gabor Szilasi’s previously unpublished photographs of the Budapest revolution and Corridart. My research also led to finds in the Médiathèque littéraire Gaëtan-Dostie, from which we selected handwritten pages from Pierre Vallières’s Nègre blanc d’Amérique, as well as student newspapers from 1968 and feminist literary documents. In total, we integrated almost fifty artworks, films, and documents into the five sections of the exhibition.

A major program of films is being offered at the Cinémathèque québécoise. It includes an exhaustive selection of thirteen films chosen by Didi-Huberman for the exhibition at Jeu de Paume in the fall of 2016, to which have been added Canadian works such as Alethea Anarquq-Baril’s Inuk en colère and Richesse des autres by Maurice Bulbulian and Michel Gauthier.

JD: Among the activities that you designed for making the exhibition accessible to the public are a major colloquium that aims to extend reflection around the issues raised by the works and to embody them in our specific situation. Can you talk about the major axes of this reflection and the importance that you place on this aspect of the project?

LD: We thought about many activities when our agreement was confirmed with Jeu de Paume and the Didi-Huberman, and I immediately had the idea to place them under the rubric L’art soulève (Art rises up), echoing those that we already use for exhibitions, L’art existe (Art exists) and cultural mediation, L’art observe (Art observes). To explore the questions raised by Uprisings in greater depth and continue its interdisciplinary grounding, we hoped to have people from various theoretical fields become involved. First, I consulted a number of colleagues at UQAM, to tell them about the undertaking and solicit their participation. I formed a working committee composed of Anne Philippon and Philippe Dumaine – two pillars of the gallery – as well as my colleague Guillaume Lafleur from the Cinémathèque and professors of art history, visual and media arts, and communications. Very early in the process, the question came up of a day-long seminar organized by the art history department and planned for November, which would be a better time than the start of the school year if we wanted a large number of students at various academic and intellectual levels to attend. Titled Des voix qui s’élèvent (Raised voices) and organized by Marie Fraser, Annie Gérin, Dominic Hardy, Vincent Lavoie, Edith-Anne Pageot, and Thérèse St-Gelais, this transdisciplinary day included lectures, roundtables, and performances around the theme “Speaking out by artists and activists whose works and actions provoke social uprisings and changes and involve a multitude of issues, including oppression, social marginalization, exclusion from history, and wounds to memory.”

Second, we counted on the participation of the curator, who wanted to be involved in a colloquium organized around the opening of the exhibition. To assist me with the organizational tasks, I asked Katrie Chagnon, whose doctoral dissertation, “De la théorie de l’art comme système fantasmatique: les cas de Michael Fried et de Georges Didi-Huberman,” offers an in-depth analysis of the work of the two art historians named in her title. Katrie and I sketched out a proposal for the colloquium titled Uprisings: entre mémoires et désirs, placing memory and desire as mirrors of each other and as central to the question formulated by Didi-Huberman in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue: “How do images draw so often from our memories to give shape to our desires for emancipation?” Like the exhibition, the colloquium gives the curator the podium, and he has the immense privilege of making the inaugural speech. There are opportunities to listen to colleagues studying various uprisings in Europe and North America, including Philippe Despoix, Dalie Giroux, Jean-François Hamel, Ginette Michaud, and Tamara Vukov; to attend an interview conducted by Katrie Chagnon with Didi-Huberman; and to have the exceptional presence of poet, novelist, and essayist Nicole Brossard, who speaks about the ethical duty of resistance.

Finally, many artists will host the public over the weeks for lectures and exchanges, including Taysir Batniji, Dominique Blain, Gabor Szilasi, Enrique Ramírez, Étienne Tremblay-Tardif, and the founders of the magazine Québécoises Deboutte. In the context of a university gallery, it is extremely stimulating to embody movements of ideas in concrete reality and have works of art dialogue in the exhibition space. It is certainly the greatest privilege that Uprisings offers us. Translated by Käthe Roth

Jacques Doyon is editor-in-chief and director of Ciel variable.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 110 – MIGRATION ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Louise Déry. Hosting and Presenting of the Exhibition Uprisings – Jacques Doyon ]