[Winter 2019]

By James D. Campbell

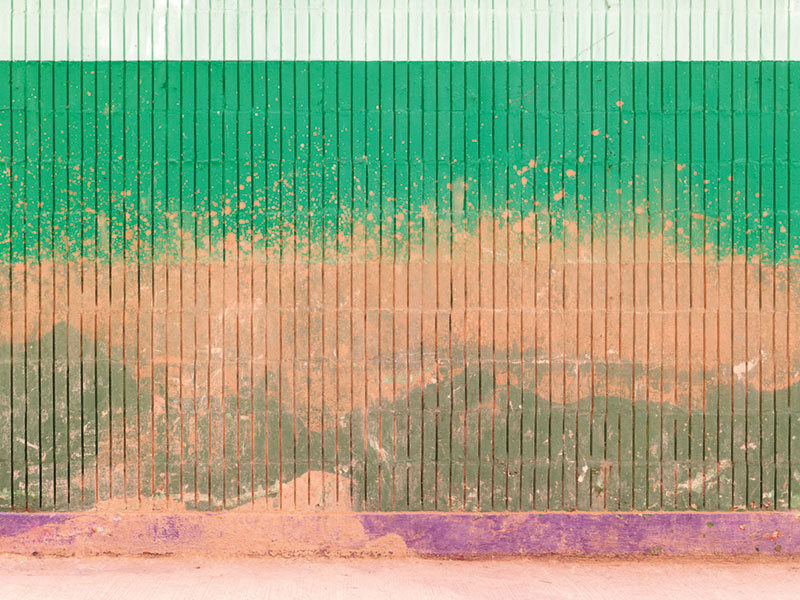

The photographs of Belgian artist Bert Danckaert have been likened to abstract paintings, but the family resemblance resides more in the facture than in the finished work of art. Given his uncanny eye for the compositional “Eureka!” behind the lens, it’s as though he is using masking tape in the same way that a hard-edge abstract painter does, and cropping with an uncanny order of geometric precision, to produce images that beguile us with their apparently simple, clean and pristine minimalist ethos. Appearances can be deceiving, however, because his palette, startling in its bold declarative chromaticity and hallucinatory in its clarity, owes rather more to conceptualism and to wayward, if stalwart, forebears such as Ed Ruscha, Stephen Shore, and Lynne Cohen than to those painting mavens – I mean, the hard-edge abstractionists.

The strange particularity of the places that Danckaert seizes upon is worth noting. Those places may be akin to those we pass by every day on our way to and from work in our urban neighbourhoods, but he places them in perceptual brackets, and they assume a heightened identity outside the quotation marks of the quotidian.

Seemingly anchored in or subservient to a Cartesian grid, in fact these photographs radically exceed any coordinate system whatsoever. They may be localized in the built world, but they do not trade on its architectural tropes. Instead, his images are read as surreal icons of the lived environment. Such is their aura that they exert a magnetic pull on the viewer. They enjoy great and startling self-presence and even (although the inner city is admittedly no Garden of Eden) the freshness of a first day. Danckaert looks, thinks, and shoots with virtual simultaneity and demonstrates an abiding interest in structure, serial imagery, and the mundane. His work has always clearly had an affiliation with conceptual art. He has an eye for the absurd, but his aesthetic is not anchored in it.

Inge Henneman, curator of the Antwerp Photo Museum, has said insightfully about Danckaert and his work, “The bizarre cityscapes of Bert Danckaert deal with the same paradox of abstractive simplicity and a complexity of meaning and metaphor. Danckaert’s still lives breathe a superficial flavour, a strangeness that is found in the familiar. Coincidental installations of sidewalks, walls and street furniture refer more to minimalist art than to conventions of street photography. In these absurd scenarios a recognizable, all too banal reality appears stage-set, props and trompe-l’oeil included, while the actors are absent.”1

The actors are absent, as Henneman notes, and this thematic absence is also a hallmark of the people-less non-place as understood by French thinker Marc Auge. But the palette here is overloaded, pushed to the maximum, almost to the level of what we might call an instinctual hyper-cathexis of the chromatic. But the photographer is not, as it were, simply stacking his deck. Chroma rules this work – and with a sublime and telling insistence.

Danckaert has said that he became a photographer “to be in the world and to work with the world,” and this aspiration is one that still marks his work.2 That work is less about identifiable geographic locales (even when in China) than with sudden moments of perceptual clarity and chromatic seizure that he sites and constructs simultaneously. His images remind one of Robert Walker (without the streetwise funk), Lynne Cohen (without the pointed, even wilfully patent absurdity), and Andreas Gursky (without the solemn grandeur of multiplicity). He also has a lot in common with the New Topographics photographers of the 1970s (Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Nicholas Nixon, Stephen Shore and others).

Danckaert’s toolkit is one he has always used and feels most comfortable with: a Canon 5D Mark II, the same lens (50 mm, because as he says, “it doesn’t seem to transform reality”), computer, Photoshop, Epson printer, and Hahnemühle paper. He was, by his own admission, inspired by the example of his friend, the recently deceased photographer Lynne Cohen. The dialogue they enjoyed was one that ended only with her demise. Both artists exclude any human figure from their work, and they both value the surreal.

It is worth pointing out that what seems quotidian in Dankaert’s work is removed from the quotidian through cropping and framing and sage sleight of hand. It then becomes subject to its own rules. Against the original context is his own contextualization, which opens the doorway to a strange dimension alleviated of attachment to place and singularity – which is not to say that his photographs are not singular, because they are. But they magnify sites in the urban core with a disturbing specificity, in which the icon is not the instantly recognizable Eiffel Tower, say, but the painted wall of a cheap hotel in the Rue Pajol courtesy of Willem de Kooning or Ludwig Sander.

Danckaert has been criticized by some for the “rigidity” of his approach, but that would be to mistake his conceptual agenda for the enervating spectre of sameness – this wall, that forty-five-degree angle – when what is subversive and new in his work is precisely that might be achievable given that mutable agenda. Consider Ed Ruscha, the quintessential California conceptualist, who he admires as much as he does Cohen. Ruscha’s first book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962), featured photographs that he took while traversing Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma City, across Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Those en route photographs, like Danckaert’s, like Cohen’s, have no people in them, and they are not about anything as conventional narratives. Instead they explore the banal with telling obsessiveness. We can trace Danckaert’s preoccupation with the quotidian back from his recent series True Nature to Ruscha’s exploration of the everyday and the commonplace in his paintings, photographs, books, prints, and drawings. Of course, I am not citing any hardcore lineage here, conceptual or otherwise, because Danckaert is a maverick artist who has gone his own way. Still, Ruscha’s familiar, and even banal, subjects were obviously an inspiration and perhaps even a model for emulation.

It’s worth noting that only one photographer of the New Topographics movement, Stephen Shore, shot in colour. It seemed to heighten the overall atmosphere of detachment and emotional abandonment in his photographs of anonymous streets and crosswalks. This closely relates to the effect of the chromatic plenitude in Danckaert’s work on its lonely purviews. (Shore was also, it should be remembered, influenced by Ruscha’s work.)

Together with his thematic interest in the quotidian as subject matter and his highly cathected chromatic idiom, Danckaert is a seasoned explorer of sundry spatial possibilities that set his work apart. His take on exploring the nature of urban space is both novel and arresting. Like the New Topographic photographers who preceded him, Danckaert, supreme poet of vernacular language in photography, finds a compelling, quixotic lexicon in the commonplace, and conjures up a new and strangely haunting beauty from the urban banal.

2 Bert Danckaert, “Interview,” The Art of Creative Photography, https://artofcreativephotography.com/contemporary-photography/bert-danckaert/.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator who writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Bert Danckaert, True Nature — James D. Campbell, Strange Oases of the Seen: Images of the Built World ]