[Winter 2019]

By Laurie Milner

Kinship, broadly defined, is a core concept in Montreal artist Marisa Portolese’s photographic practice. We see kinship, in the context of family relations, enacted in Antonia’s Garden (2007–11), a series of portraits, still lifes, and landscapes that traces the psychic effects of trauma and the will to heal in three generations of Portolese’s maternal family. Large-scale colour photographs show family members – distant and still – among tangles of weeds and grasses, in crumbling interiors and aseptic hospice rooms. Things – ornate heirlooms, blistered and puckered with age; the intact skeleton of a horse, its bones brittle and bare – convey the same ceaseless solitude that we see in the human portraits. The encounters are all staged, but no less real for that reason. Portolese is aware of the constituent nature of her photographic interventions and mindful of their effects; we can sense her reassuring presence in the candour with which her subjects perform themselves and witness her empathetic participation in the redemptive story that unfolds. Across the series, we observe the concept of family, as a pre-given set of relations, quietly eclipsed by kinship, as the active and abiding practice of connection.

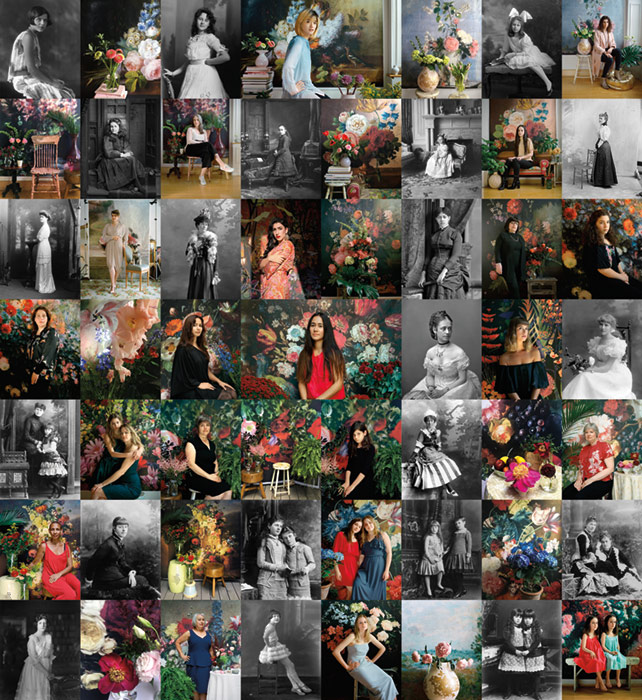

Kinship as connection is integral to the three-part Belle de Jour series that Portolese produced between 2002 and 2016. The models for the photographs are her female friends, colleagues, and acquaintances; many are from Montreal and many have creative practices of their own. In Belle de Jour I (2002) and Belle de Jour II (2014), Portolese stages the models in art-historically informed images: sensual, forthright, and saturated with colour, the photographs evoke the structure and atmosphere of unnamed classical and modern paintings while affirming the sovereignty, grace, and vulnerability of the female models. In Belle de Jour III: Dialogues with Notman’s Portraits of Women (2016), the historical references become more explicit as Portolese begins a conversation with the work of nineteenth-century Montreal photographer William Notman (1826–91). In the sole exhibition of Belle de Jour III, curator Zoë Tousignant interspersed portraits of Victorian women by Notman among Portolese’s works, bringing the formal relations across time that characterize the Belle de Jour series as a whole into sharper focus and auguring an affective shift in Portolese’s practice. As Portolese discovers a kindred spirit in Notman – a photographer who, like her, portrays women as independent, agential, and unique – a new tone emerges in her work, one that is more curious than critical, more tender than defiant, more radiant than restrained.

In the context of a year-long residency at the McCord Museum (2017–18) devoted to the study of backdrops and props in Notman’s portraits of women, Portolese created In the Studio with Notman,1 a series of portraits of women and girls in lush, inventive studio settings. In the images, enlarged photographic reproductions of flower, bird and landscape paintings are suspended behind the sitters as resplendent backdrops to the performances of identity that occur before the camera. The sitters, who have chosen their attire with the backdrops in mind, take their positions among props – arrangements of flowers, foliage, and decorative objects – that are also keyed to the paintings, resulting in lively cascades of colours and patterns across the portraits and the creation of illusory and sometimes unanticipated effects. In Lili Michaud, a burst of fern leaves in the foreground is echoed in the printed textile of the sitter’s dress; behind her, the tip of a yellow gladiola – the colour of the sitter’s hair – rises from a profusion of fresh flowers to touch the stamen of a blue-tinged orchid in a still-life painting by Jan Frans van Dael (1820). In a portrait of two young sisters, Josephine and Penelope Wilson Rose, a yellow finch in the backdrop painting (John Gould, Birds of Great Britain, 1862) appears to sip the nectar of a white chrysanthemum on a table beside the girls, while its painted companion watches over the scene – an image of protection, perhaps, or a foreshadowing of the immanent sexual awakening of the girls.

Although Notman’s practice may have inspired some of the whimsy in Portolese’s portraits, it is to the history of painting that their gravitas is owed. In Julia Inniss, a young woman reclines on a curving chaise longue in the languid posture of a nineteenth-century odalisque. Like David’s Madame Récamier (1800) – the source for Ingres’s similarly postured Grande Odalisque (1814) – Julia Inniss supports her upper torso on her left arm as she twists to look directly toward the viewer. The tips of her gently splayed fingers touch the side of her face in a gesture that recalls Ingres’s portrait of Madame Moitessier (1884–86). Unlike the female figures in these nineteenth-century paintings, however, Inniss presents a clear, focused gaze and an aura of self-possession. An arrangement of pink and white blossoms and green foliage diffuses the natural light coming through an off-frame window and casts the sitter in partial shade. Behind her, an enormous pink blossom, painted with light, quick strokes, appears to droop under the weight of its petals (Jean-Marc Nattier, detail of Manon Baletti, 1757). A visible crack runs through the painting, defining an arc that echoes the contour of the sitter’s body. The symbolism in the portrait is as integrated and discrete as in an annunciation painting by Piero della Francesca: Julia Inniss, we learn, is a portrait of a woman expecting her first child.

Similarly understated symbolism operates in a double portrait of Molly Moreau and her infant daughter Greta Bergen. The sitters are positioned between two umbrella plants whose glossy leaves fan out from spindly stems; a hazy mountain landscape (Albert Bierstadt, Mount Hood, 1869) fills the background space. Moreau holds her daughter against her chest, and the two look toward the viewer. To their left, behind the child’s back, one stem of the umbrella tree rises from its woody trunk to transcend the horizon line in the mountain scene; a new compound leaf, appearing weightless in the air, radiates from the tip of the stem. In its skyward reach and teetering orientation, the pinwheel leaf affirms its liveliness; at the same time, it creates a window onto its own mortality. The upright stem and its horizontal counterpart define a frame in the upper-right corner of the painting, bringing into view three conifer trees painted at different stages of growth and decay. One of the trees is dead, its lifeless trunk standing parallel to the jaunty new growth of the umbrella tree – an allegorical reminder in Portolese’s photograph that death is part of the cycle of life.

For the sitters, the performance of the self that occurs in the photographic encounter is a complex and relational one. The sitters come as themselves: they wear their own clothing, reveal only those aspects of themselves that they wish to reveal, and have the right to eliminate any photographs they do not like. At the same time, they are attuned to the historical precedents of the project: in advance of the photo session, each sitter receives a mood board that includes portraits of Victorian women by Notman and images of the backdrop painting and props that will be set up in the studio; the mood board familiarizes the sitters with the environment, guides them in the selection of clothing, and orients them toward the aesthetic effects that Portolese has in mind. During the photo session, Portolese places a selection of Notman portraits on the floor before the sitters. The sitters thus perform their selves in relation to performances of self by other, historical women. In this way, too, Portolese creates the conditions for the sometimes-unexpected realization of kinship.

The installation of In the Studio with Notman at the McCord Museum, organized by Hélène Samson, McCord Curator of Photography, activates the rich web of connections and conversations across time and space that are the stuff of Portolese’s practice. It begins with a floor-to-ceiling enlargement of Notman’s portrait of Annie McDougall – an artist and photographer in her own right – who sometimes assisted Notman in the studio.McDougall appears relaxed and proper, as befits a Victorian woman; however, there is also an air of eccentricity about her, evident in the curious hat that she sports and the scuffed shoes that peek out from beneath the hem of her dress. It was this photograph that initially fired Portolese’s curiosity about Notman’s portraits of women and prompted her to research his studio practice. In the studio setting of the McDougall portrait, we see the props and backdrops that Notman used to fashion his portraits, now tucked into corners and set on windowsills, waiting for the right client to appear. Further into the exhibition, a patchwork of photographs by Notman and Portolese lines the walls of a small alcove, revealing the associative method that Portolese employs and making ever more points of possible connection vivid.

Laurie Milner is a professor at Concordia University, where she teaches seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century art in the art history department and contemporary art, writing, and theory in the MFA studio arts program. Milner also runs her own writing and editing business.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Marisa Portolese, Kinship as a Practice: In the Studio with Notman — Laurie Milner ]